Reading (and Listening to) “Time’s Echo”

January 31, 2024

New York, N.Y.

Music has the power to speak very directly to us over decades and centuries. Yet often some context and additional information can enhance the experience. The innovations of Beethoven’s Third Symphony, for example, can become more evident with knowledge of the earlier symphonies of Haydn and Mozart. Familiarity with the later works of Beethoven and other composers allows us to consider the Third Symphony as a pivotal work in western music.

Some extramusical knowledge is also helpful. In the case of the Third Symphony, knowing the famous story about Beethoven’s original dedication of the symphony to Napoleon and his violent erasure of that dedication places the music in an historical era of Enlightenment optimism, gives us some clues about Beethoven’s concept of the hero, and reveals his political disappointment when Napoleon declared himself emperor. Composers live within their times, and they reflect those times as well as help define them.

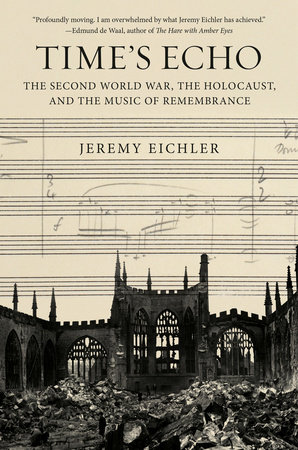

For music composed in response to World War II and the Holocaust, this historical perspective is essential. That’s the value of Jeremy Eichler’s brilliant and beautiful book Time’s Echo: The Second World War, the Holocaust, and the Music of Remembrance (Knopf, 2023). Historical and musical context abound in this enlightening examination that focuses on four iconic compositions but encompasses much else as well.

Jeremy Eichler is uniquely qualified for this fascinating exploration: He is chief classical music critic for the Boston Globe but also has a Ph.D. in modern European history from Columbia. For this book, he has visited crucial sites and dived deep into archives to explore the historical nooks and crannies. This is a very deep engagement with the subject matter that weaves together illuminating connections across time and space. Eichler’s writing about the music itself is the epitome of non-technical clarity.

History tends to be messy, and one of this book’s many strengths is that Eichler doesn’t gloss over the problematic natures of the composers and compositions that he discusses. He wants you to know everything about this music and their composers and the times in which they worked.

In his “Prelude,” Jeremy Eichler makes an argument for what he calls “deep listening, that is, listening with an understanding of music as time’s echo.”

Deep listening is to the memory of music what a performance is to a score: Without a musician to realize a score, it is nothing but a collection of lines and dots lying mute on a page. Similarly, without deep listening there is no memory in music’s history. Instead, we have the disconnected sounds of a Schubert symphony streaming into an empty room. We have “classics for relaxing.” Without deep listening, the voices of the past are whispering into the void. (p. 15)

Throughout the 19th century, Europe had a rich heritage of Jewish composers, including Felix Mendelssohn, Giacomo Meyerbeer (almost forgotten these days), Gustav Mahler, and the up-and-coming Arnold Schoenberg. But there also existed an ugly history of anti-Semitism, including Richard Wagner’s famous attack on Jewish composers in his 1850 essay Judaism in Music.

After Adolf Hitler rose to the position of chancellor of Germany in 1933, anti-Semitism became a national policy. Books by Jewish authors were banned and burned; music by Jewish composers was banned, and Jewish musicians found themselves sidelined.

Richard Strauss: Metamorphosen

Of the four composers that Eichler focuses on, Richard Strauss (1864 – 1949) is certainly the most problematic.

Strauss was probably not anti-Semitic himself. Some of Strauss’s best operas (including Electra, Der Rosenkavalier, and Die Frau ohne Schatten) have librettos by Hugo von Hofmannsthal, who was of partial Jewish descent. As I discussed in my previous blog entry, Strauss courageously worked with Stefan Zweig for his opera “Die schweigsame Frau,” and because of Zweig’s involvement, the opera was banned after three performances. Strauss had a Jewish daughter-in-law, and his grandchildren were Jewish.

But in other ways, Strauss went along with the anti-Semitic policies of the Nazi government. In 1933, when Jewish conductor Bruno Walter was suddenly prohibited from conducting the Berlin Philharmonic, Strauss stepped in to take his place (p. 70). Similarly, when Arturo Toscanini resigned from conducting the Bayreuth Festival in protest against the Reich, Strauss was again the reliable substitute. (pp. 83–84)

Eichler quotes an astonishingly angry 1935 letter from Strauss to Stefan Zweig when Zweig was working on one-act librettos for Strauss that never came to fruition:

Your letter of the 15th is driving me to distraction! This Jewish obstinacy! Enough to make an anti-Semite of a man!... Who told you that I exposed myself politically? Because I have conducted a concert in place of that obsequious, lousy scoundrel Bruno Walter? That I did for the orchestra’s sake. Because I substituted for Toscanini? That I did for the sake of Bayreuth. This has nothing to do with politics.... Because I ape the president of the Reich Music Chamber? That I only do for good purposes and to prevent greater disasters!... (p. 87)

Strauss’s Jewish daughter-in-law, Alice Grab Strauss, survived the war, as did her two children. So if Strauss was collaborating with the Nazis to ensure their safety, he was successful. But several of Alice’s relatives were killed in the extermination camps. (pp. 99–101)

Richard Strauss’s 1945 composition Metamorphosen is one of his most mysterious works. It’s certainly not a tone poem for it has no narrative. Not even the meaning of the title is clear. The only clue that Strauss has left is the music’s quotation of a theme from the funeral march of Beethoven’s Third Symphony under which Strauss wrote in the score: “IN MEMORIAM!” (p. 106) That couldn’t refer to Hitler, could it? Or is it an ironic reference to Beethoven’s erased dedication to Napoleon? Eichler writes:

More recent program annotators have typically framed Metamorphosen as a work lamenting the bombing of the German cities and opera houses. Yet it can perhaps most persuasively be heard as a rueful philosophical meditation on the opacity of the self and, by extension, as a belated and still intensely private grappling with some portion of his own willful blindness — in rejecting and later mocking German music’s ethical charge, in so decisively placing the individual above the collective, in justifying his actions through a morally untenable divide between politics and art, and in associating himself with a categorically evil regime that had, in only twelve years, brought about the destruction of the entire edifice of German culture. (p. 107)

This performance of Metamorphosen by the Norwegian Chamber Orchestra is remarkable on two levels: The 23 musicians are playing without a conductor, and they are also playing from memory without scores.

Eichler concludes that if Metamorphosen is understood as a type of penance on the part of Strauss, it’s too little, too late:

Few, however, would dispute the music’s brilliance, its lofty bearing as a late work, its majestically sorrowing beauty. No doubt for those reasons, Metamorphosen is performed today more frequently than just about any musical memorial from the era of the Second World War. Part of its spell also lies in its binding together of opposites: sincerity and inscrutability, expression and elision. The music’s own profound sense of knowing stands in perfect equipoise with its profound unknowability. (p. 120)

Arnold Schoenberg: A Survivor from Warsaw

The problem of “unknowability” does not afflict A Survivor from Warsaw. Even if you previously knew nothing about this 7-minute cantata, the music is so clear and direct that you would quickly figure it out.

Arnold Schoenberg (1874 – 1951) is one of the titans of modernism in 20th-century music. With highly charged late-romantic works like Transfigured Night (1899), Schoenberg began exploring the limits of traditional tonality and harmony. He strove for the “emancipation of dissonance,” stretching rules until they broke. To maintain order, he replaced it all with a compositional system called serialism or twelve-tone. Compositions were then based on the permutations of a tone-row built from all 12 notes of the octave. For this invention, Schoenberg became extraordinarily influential in the post-war avant-garde , but also one of the most reviled composers of all time.

To Schoenberg, this replacement of traditional harmony with the twelve-tone system was an essential part of the evolution of music, and specifically, German music: “I have made a discovery thanks to which the supremacy of German music is ensured for the next hundred years,” he said. (p. 65)

In 1898, following a pogrom in Vienna, Schoenberg had converted to Christianity (p. 42). But following the rise of Hitler, by 1934, Schoenberg was more prescient than most in understanding how serious the situation had become. He told one of his former students that the Nazi program was “nothing more nor less than the extermination of the Jews!” (p. 131) Schoenberg embraced his Judaism as never before and told someone else “I will start a movement which will unite the Jews again in one people and bring them together in their own country to form a state.” (p. 130) He had already left Germany first for France and then the United States.

Some of Schoenberg’s family members were not so fortunate. His brother, a niece and nephew, and a cousin did not survive the war. (p. 138)

After the war, in 1947, Schoenberg accepted a commission for “a work that would commemorate Jewish suffering at the hands of the Nazis.” This might have taken the form of a solemn elegy, but Schoenberg evidently had something in mind that would instead highlight the horrors of the extermination camps. In less than two weeks in August, 1947, he composed A Survivor from Warsaw.

The music is twelve-tone, and even some of those who despise the technique might admit that for a composition like this, the harsh dissonance is entirely appropriate. With a type of rhythmic but unpitched speech, a narrator tells of an incident in a camp where the brutality of the guards leads to the prisoners rising to sing the Jewish prayer known as the Shema Yisrael.

Here is a performance conducted by Simon Rattle with bass-baritone Franz Mazura from Rattle’s 1996 television documentary series, Leaving Home:

Eichler devotes most of Chapter 6 to the story of the first performance of A Survivor from Warsaw. Conductor Serge Koussevitzky passed, possibly because of the intense nature of the work. But then Schoenberg got a letter from a conductor named Kurt Frederick, also from Vienna, who had come to the United States in 1938 and settled in Albuquerque, New Mexico, where he ran an amateur ensemble called the Albuquerque Civic Symphony Orchestra.

And this is how A Survivor from Warsaw received its premiere performance in a gymnasium at the University of New Mexico. It’s a great story!

Benjamin Britten: War Requiem

The other two compositions that Jeremy Eichler discusses both date from 1962, but the stories behind them both begin some two decades earlier, in the early years of the Second World War.

On November 14, 1940, the Germans conducted a bombing raid on the city of Coventry, resulting in hundreds of dead and injured but also destroying much of the city’s historic cathedral.

At that time, composer Benjamin Britten (1913 – 1976) was living in a Brooklyn townhouse with tenor Peter Pears and others. Both were lifelong pacifists and in 1942 registered as Conscientious Objectors. (p. 195) Eichler tells how after the premiere of Britten’s opera Peter Grimes in 1945, Britten met violinist Yehudi Menuhin, and the two of them went to Germany to perform at various locations beginning at the Bergen-Belsen displaced persons camp. Under different circumstances, the gay pianist and the Jewish violinist would both have been sent to an extermination camp, but now they played not only Bach but the music of Mendelssohn, which had been banned by the government since 1933. (p. 197)

The rebuilding of Coventry Cathedral took over a decade. Scottish architect Basil Spence came up with a plan that combined a modern design and incorporated the remains of the original 14th-century structure. (p. 210) Britten’s War Requiem was performed at the consecration of the new cathedral on May 30, 1962.

War Requiem has an unusual structure. The traditional Latin Mass for the Dead is sung by a chorus and soloists accompanied by a large orchestra. At various times, a small chamber ensemble accompanies soloists in settings of poems by Wilfred Owen, who was killed in action in France in the First World War at the age of 25 one week before the war’s end.

In the War Requiem, Britten was able to deploy Owen’s verse like small detonations placed perfectly at key fulcrum points in the requiem text, thereby creating a work that simultaneously honors the dead in solemn tradition-minded tones and refuses to neutralize their deaths, to airbrush the brutality of war, or falsely separate institutional religion from the patriarchal power structures that made war possible in the first place. As a result, the War Requiem never lets the listener escape into a facile “rest in peace” sense of consolation. (p. 213)

When searching for performances of War Requiem on YouTube, I liked one conducted by Marin Alsop but it has no subtitles, which I think are essential for this work.

In the video I chose, italic subtitles are used to differentiate the Wilfred Owen poems from the text of the Mass, but the titles of the poems are not identified. They are:

This performance by the Brisbane Philharmonic Orchestra in Queensland, Australia is preceded by a ceremonial Welcome to Country song and statement from an elder of the Turrbal people of Brisbane.

In the first performance of War Requiem, Peter Pears sang the tenor part, and the great German singer Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau was the baritone. To complete the multinational representation, the Russian soprano Galina Vishnevskaya was to sing the soprano part, but the Soviet government refused to allow her. (p. 219)

As Jeremy Eichler points out, it seems very strange for a reconstructed cathedral destroyed during the Second World War to be consecrated with poems written during the First World War. A war of civilian bombings was being remembered with poems of trench warfare. But the British casualties in the First World War were twice those in the Second (p. 207) and that war still loomed large in British consciousness. I suppose also that poems equivalent to Owens but from World War II were rather scarce.

The choice to restrict the settings to poems from the First World War caused another problem: The War Requiem never even alludes to the Holocaust. This is something that Eichler discusses at length (pp. 220–224). That omission tarnishes what is otherwise one of Britten’s best compositions.

Dmitri Shostakovich: Symphony No. 13 (“Babi Yar”)

As the German army marched toward the Soviet Union in the summer of 1941, they inflicted what is sometimes called the “Holocaust by bullets” that remains largely unknown in the Western world because Western armies never saw it.

In September, the Germans took Kyiv and a week later ordered all Jews to assemble at the corner of two streets. They were marched toward a ravine called Babyn Yar in Ukrainian, Babi Yar in Russian. Over two days (according to meticulous records kept by the Nazis), 33,771 Jews were murdered, mostly shot in the back of the head so they fell into the ravine. Over the first six months of the German invasion, a total of 600,000 Soviet Jews were killed; over the course of the war, the total was 2.5 million. (pp. 235–6)

The Soviet government was not hesitant to expose German atrocities. But they would not specifically cite Jewish deaths. “Do not divide the dead!” they said. (p. 242)

At Babyn Yar, the silence was complete. First the Nazis had destroyed the evidence; then the Soviets had destroyed the memory. Together they formed a perfect seal.

Despite all attempts by the Soviet government to suppress this chapter of the Holocaust, the memories would not go away, and when 28-year-old Siberian-born poet Yevgeny Yevtushenko couldn’t find the site of the massacre, he reacted with a poem that begins:

No monument stands over Babi Yar.

A drop sheer as a crude gravestone.

I am afraid.

Today I am as old in years

as all the Jewish people.

It goes on to cite not only the anti-Semitism that had plagued Europe for centuries, but also the anti-Semitism right at home:

How vile these antisemites —

without a qualm

they pompously called themselves

the Union of the Russian people!

The poem was published in a literary gazette on September 19, 1961. (p. 255) This was during the Khrushchev Thaw, so Yevtushenko avoided the Gulag. Instead, as Eichler writes,

The response was electric. Copies flew from newsstands across the country, and the poet claims he received some twenty thousand letters. The official reaction, however, was less sanguine. “Babi Yar” was denounced as bourgeois, as a falsification of history, and, worst of all, as a shameful betrayal of Russia’s own tragic losses during the war.

One of the early readers of “Babi Yar” was composer Dmitri Shostakovich (1906 – 1975) who immediately set it to music.

I’ve written about Shostakovich before. He went through hell during his compositional career, becoming the target of Soviet authorities who condemned the “formalist” (that is, non-Soviet-realist) tendencies in his music, while at the same time (in my memory of the 1970s), being thought of in the West as a Soviet toady. Shostakovich’s music still comes with a lot of baggage.

Shostakovich’s setting of “Babi Yar” became the first movement of his Symphony No. 13, to which he added settings of four other Yevtushenko poems. Although Shostakovich didn’t give the symphony a nickname, it is often referred to as the Babi Yar symphony. It premiered in 1962, seven months after the premiere of Britten’s War Requiem.

This wonderful performance by the Michigan State University College of Music with baritone Mark Rucker (a Professor of Voice at the College) is fully subtitled:

At some point, someone sent Shostakovich a recording of Britten’s War Requiem, about which he said:

I am playing it and am thrilled with the greatness of this work, which I place on a level with Mahler’s Das Lied von der Erde [Song of the Earth] and other great works of the human spirit. (p. 271)

Their admiration was mutual, and in 1969, Shostakovich dedicated his Fourteenth Symphony to Britten. In 1971 and 1972, they visited each other, Britten and Peter Pears travelling to Leningrad, and Shostakovich and his wife visiting Aldeburgh, where Britten showed him sketches of what was to be his final opera, Death in Venice. (p. 283) (In one of my early opera-going experiences, I saw Peter Pears in the American premiere of Death in Venice at the Metropolitan Opera on October 18, 1974, and wrote a glowing review for my college newspaper.)

Although I was familiar with all four of these compositions prior to reading Jeremy Eichler’s book, I had never thought of them as being related to each other, or of being somehow different from the other music of these composers. Eichler forced me to listen deeply, to hear “time’s echo,” and the connections he revealed and the questions that he raised will forever be part of how I hear this music in the future.