Building a Virginal: Actual Music

May 11, 2023

Roscoe, N.Y.

The virginal that I’m building from a kit now has 20 jacks installed, each with a plectrum and a cloth damper, ranging from B♭3 through F5, a range that allows me to play the first four measures of Bach’s Prelude in C Major from Book 1 of the Well-Tempered Clavier:

The tuning is still somewhat unstable, some of the jacks sometimes don’t return properly (a problem called “hanging”), the undamped strings vibrate sympathetically, and the touch is very uneven. (More on this later.) Also, even in the best of conditions, I don’t play very well.

Getting to this point required about 15 hours of work spread over three days: May 4, 7, and 8, which I’m labeling as Construction Days 21, 22, and 23.

One reason it took so long is that for many of the pairs of jacks, I had to re-pin the left bridge. I was forced to do what I definitely didn’t want to do ever since I first read this section about the left bridge pins on page 46 of The Troubadour Virginal Construction and Maintenance Manual:

If you’re just a little off you can probably adjust the distances by tapping your pins one way or another, as long as the pins still angle over the string. If you’re still just a little off, there’s no harm done. If you’re further off than that, there’s no choice but to pull the pins, plug the holes with toothpicks, and try again.

The problem with my original pinning of the left bridge resulted from my reliance on a tool I built that was conceptually flawed. I assumed the string should be parallel to the face of the jacks, and that’s not true. I found better positions for the pins by inserting pectra in the jacks extending ⅛” from the face of the jack, and then positioning the wire so that the outside edge of the wire (away from the jack) met the tip of the plectrum.

I had to trim down the bottom of each jack so that the plectrum was just underneath the string. I was going to build a little stand for my drill with a sanding disk attached, but it seemed to stand up well by itself:

I am still reluctant to make the jacks too short, so right now, each plectrum is right below the string that it plucks. It should be about 1/16” below the string.

I am not going to show a video of me inserting a plectrum and carving it down to size, or closeups of the resultant plectra. The care and carving of a plectrum is apparently an acquired skill, and I have not yet acquired it. I tried to imitate the technique shown in this Zuckermann video:

But the plectra are so tiny that it’s extraordinarily hard to be consistent. I hope to document my approach when I get better at it — when I am truly a plectrum-carving ninja.

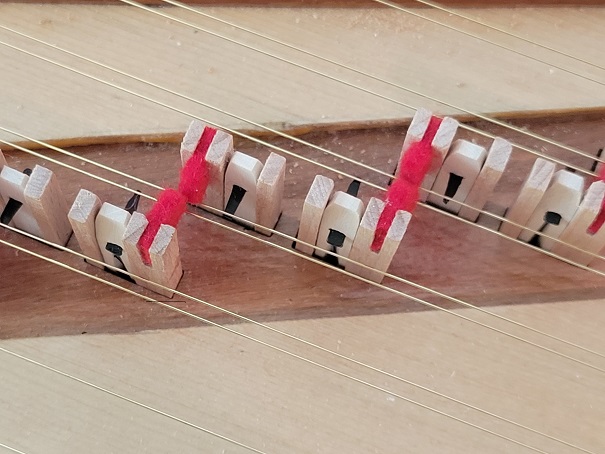

When I began inserting the damping cloth in the slots in the jacks provided for that purpose, I was startled to realize that the dampers of opposing jacks touched, and it was necessary (as described on page 56 of the Construction Manual) to trim away the top of the damper so they don’t interfere with each other:

But it seemed to me like a design flaw. If the jacks were designed so that the damper slot was on the right of the tongue rather than the left, there wouldn’t be a problem.

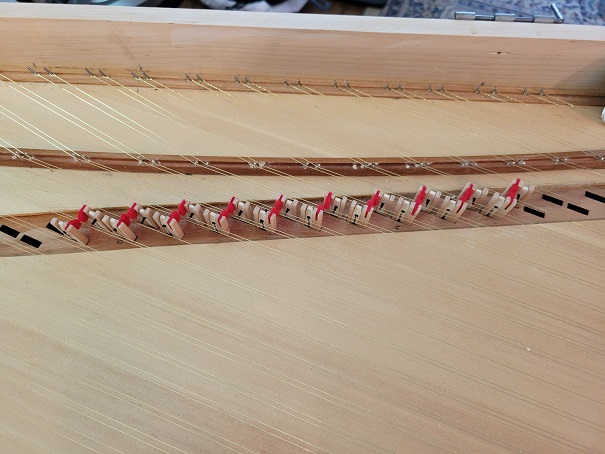

Here are the 20 jacks with plectra and dampers:

Zuckermann has a video about tuning hosted by intern Seymour, and I took her recommendation about the ClearTune app. It wasn’t available for my Android phone so I put on my iPad Mini, which I discovered can can sit conveniently on the back edge of the case held up by the two bridges:

The big problem that I’m experiencing at this point involves the touch. Some keys are light, and some keys require significant pressure to pluck the string. The difference results from several interrelated factors: the distance of the wire from the jack, the length of the plectrum, and the extent to which the plectrum was successfully carved down and thinned out.

But how do I even know what my target key pressure should be?

A little searching turned up this page on The Keyboard of a Harpsichord in the website of Ottawan polymath John Sankey, where he specifically discusses action weight. He writes:

The force required to depress a key is the net weight of the key and jacks plus the force required to pluck the strings. The more resonant the instrument, the lighter and slacker the strings can be, thus the lighter the action. The earliest instruments have keys and jacks that are so light that the action force is almost entirely that required to pluck the strings — the feel is as direct as that of a lute or harp….

And then he provides something quite useful: Metrics!

I am certain that it was unusual for a pre-19th century harpsichord to require a key force greater than 150 g even on plein jeu, and that most required appreciably less. The high force demanded by so many modern instruments is not based on history, but on a use of strings longer than were used in the past at the pitch at which they are now sounded. My Ross [the harpsichord he’s working on] had a c’’ [an octave above middle C] length of 375 mm, far longer than could ever have been used until the manufacture of modern carbon steel music wire, and a 2x8’ plucking force of 160 g. So, I removed the top f# key and moved the keyboard up a semitone, allowing the string tension to be reduced by 12%.

All these changes together, the plucking force is now 130 g, with a much cleaner, more direct feel of the strings. And, the sound is noticeably richer with the lower string tension. It took very little time, and nothing needed to be touched outside of the keyboard. Well worth while!

William Thomson (Lord Kelvin) once wrote, “I often say that when you can measure what you are speaking about, and express it in numbers, you know something about it; but when you cannot measure it, when you cannot express it in numbers, your knowledge is of a meagre and unsatisfactory kind.”

Now I have some numbers. But how do I measure it?