Reading “I Alone Can Fix It”

August 7, 2021

Roscoe, N.Y.

I would have preferred not reading another book about Donald Trump. He got clobbered in the election, losing to Biden by 7 million votes and 74 electors. In any reasonable universe, he would have retired to write his memoirs or painting his feet poking out of the bathwater like normal ex-Presidents.

But no. Like a petulant child, Trump continues to pretend that he won the election, and in the process convincing many millions of his most gullible supporters of this preposterous concept. Every day we continue to hear more revelations about how Trump and his cronies attempted to subvert the democratic process. The problem is that they are not yet finished, and so we must continue to be vigilant. That job includes drenching ourselves in recent history, and learning as much as possible about Trump’s vile and toxic influence and agenda.

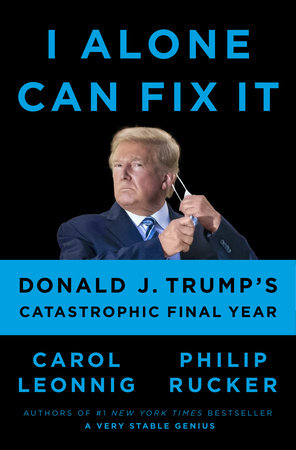

Just 18 months ago, I blogged about the book A Very Stable Genius: Donald J. Trump’s Testing of America by Washington Post reporters Philip Rucker and Carol Leonnig. Now their follow-up is available, again titled with a ridiculous quote from its subject: I Alone Can Fix It: Donald J. Trump’s Catastrophic Final Year (Penguin Press, 2021).

The year 2020 presented three challenges for Trump:

(1) COVID-19, which would have been challenging for any President, but particularly for someone of Trump’s limited intelligence and his persistent belief that people wearing facemasks look “weak.”

(2) The murder of George Floyd and other police killings, which were particularly challenging for a someone like Trump with a long history of racism, and who counted on a good part of his support from a reinvigorated white-supremacist movement. Trump is someone who simply does not believe that Black Lives Matter.

(3) The election, and the challenge here is that he lost but didn’t want to lose.

As Leonnig and Rucker write in their Prologue:

The characteristics of Trump’s leadership, blazingly evident through the first three years of his presidency, had deadly ramifications in this final year. He displayed his ignorance, his rash temper, his pettiness and pique, his malice and cruelty, his utter absence of empathy, his narcissism, his transgressive personality, his disloyalty, his sense of victimhood, his addiction to television, his suspicion and silencing of experts, and his deception and lies. Each trait thwarted the response of the world’s most powerful nation to a lethal threat...

Most of Trump’s failings can be explained by a simple truth: He cared more about himself than his country. Whether managing the coronavirus or addressing racial unrest or reacting to his election defeat, Trump prioritized what he though to be his political and personal interests over the common good. (p. 3)

Leonnig and Rucker generally take a chronological tour through the year, providing a narrative arc connecting the daily news stories that we remember (or having been struggling to forget) with additional background gleaned from interviews by the authors. Some of these interviewees are on the record while others are not.

Trump’s handling of the Covid-19 epidemic was largely a series of unforced errors. Such a crisis was not a good fit for his personality and skillset.

As one of Trump’s advisors later explained, “He’s a poor communicator to the public. He makes it about him, and it can’t be. All he had to do to win the election was if he walked up to a glass wall at a hospital and said, ‘I’m America’s president. The whole force of the United States government is behind you. I’ll do everything I can do to save lives.’ A little teary-eyed, and he’d win the election. But he said, ‘No, no, this isn’t true.’ ‘There’s a miracle drug.’ ‘We’re all going to survive.’ ‘Let’s open the country.’” (p. 114–115)

When finally the federal government brokers a deal to purchase three million doses of the first vaccine developed by AstraZeneca, Trump is excited until he learns a little more about the company that did it:

“What?” Trump asked. “It’s a British company?”

“They are the first one with a vaccine, Mr. President,” Azar said.

Trump sounded deflated. “I’m going to get killed,” he said. “Oh, this is terrible news. Boris Johnson is going to have a field day with this… I don’t want any press on this… Don’t do any press on this. Let’s wait.” (pp. 144–145)

Page after page in I Alone Can Fix It, we witness Trump’s ignorance and stupidity, and I found myself frequently cringing in embarrassment. On June 8, the highly respected National Institutes of Health Director Dr. Francis Collins is summoned to the White House because Trump wants to talk about hydroxychloroquine, and he has firsthand evidence of its efficacy.

“Let me just get Jack Nicklaus on the phone,” Trump said. “He’ll tell you what happened.”

Nicklaus, eighty, a champion golfer nicknamed “The Golden Bear” who spent a lot of time in the Palm Beach area, was an old friend of Trump’s. Trump asked his assistant to get Nicklaus on the phone, and for half an hour or so the golfer talked on speakerphone to Trump and Collins about how he and his wife, Barbara, had had COVID-19 in March. He said the president had urged him to take hydroxychloroquine, which they did, and they had recovered. The conversation was surreal. (p. 181)

Imagine being Dr. Francis Collins, and having to explain to the President of the United States how “Anecdotes where people draw a cause-and-effect conclusion are dangerous.”

Look, I don’t blame the country’s voters for putting this moron in the White House. The voters rejected him in 2016 as well as 2020, and it was only due to the hideously undemocratic and racist institution called the Electoral College that he became President anyway contrary to the will of the people.

I blame the Republican Party, which should never have allowed a man so unqualified to be President to participate in their primary elections and be nominated by the Convention. Political parties are private organizations. They can set their own rules and either not have primary elections (like the Libertarian Party) or ignore the primary results. It was the responsibility of the Republican Party to stop Trump, but they did not.

But I digress.

As is well known, Trump had a particular issue with masks. We all know that the CDC and Anthony Fauci initial stumbled on the messaging about masks (as Leonnig and Rucker report on page 73), but by April 13, the CDC began urging people to wear masks, and CDC Director Robert Redfield was eager to get the White House to set a good example. Good luck with that! Even Pence, who Redfield considered a “softer target” than Trump for his persuasions, famously showed up maskless at a Mayo Clinic tour. Trump himself was a hopeless case, saying to reporters:

“Somehow sitting in the Oval Office behind that beautiful Resolute Desk, the great Resolute Desk, I think wearing a face mask as I greet presidents, prime ministers, dictators, kings, queens — I don’t know, somehow I don’t see it for myself. I just, I just don’t.” (p. 123)

In July, pollster Tony Fabrizio was telling Trump that he could help himself politically if he demonstrated that he took COVID-19 seriously by wearing a mask.

“People tell me it makes me look weak,” Trump replied. “People see Biden and he’s always wearing a mask and he looks weak. People tell me it doesn’t look presidential.” (p. 227)

This attitude never lets up. As late as November — after Trump himself contracted COVID-19 — he didn’t want anybody in his administration wearing masks in public.

“I can’t hear you when you talk through those things,” Trump said. “I hate those things.”

“Mr. President, they work,” Azar said. “The evidence is conclusive that they work.”

He described data showing that at one meter distance between two people both wearing masks, the chance of infection was reduced by 72 percent.

“Really?” Trump asked. He genuinely seemed surprised. (p. 376)

Yet, about a week later, he’s railing against masks in the press briefing room:

“You gotta take those fucking masks off,” Trump told them.

“I’m the health secretary,” Azar said. “I have to wear a mask.”

“Once you’re at the podium, take it off,” Trump said. “Then you can put it back on.” …

Azar noted that the masks were very good at preventing the virus from spreading.

“What?” Trump asked as they moved toward the door. “They work?” (p. 396)

When protests against police killings turned violent in several cities. Trump’s instinct was to send in the military. He was particularly urged to take this approach by Stephen Miller: “Mr. President, you have to show strength… They’re burning the country down.”

At this point in the book, we begin hearing from Joint Chiefs of Staff Chairman Mark Milley, who makes his entrance saying “Stephen, shut the fuck up… They’re not burning the fucking country down.” (p. 156)

Milley emerges as the hero of I Alone Can Fix It, and this actually becomes one of the flaws of the book. Obviously Milley provided much information in interviews with Leonnig and Rucker, and he is clearly disgusted by much of what the Trump administration did and tried to do. Yet, Milley is portrayed as so heroic and steadfast battling the extremist tendencies of Trump, that I remain somewhat skeptical of the accuracy of his largely self-serving recollections.

Trump suggested MIlley, whose tough bravado the president admired, could be the commander of an operation to restore order in the city. The chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff poured cold water on that idea, realizing the president didn’t understand he didn’t command troops.

“No, no, Mr. President,” Milley said. “There’s a civilian leadership. I’m not in an operational role here.”

Milley tried to explain that Americans had a constitutional right to protest and the military should not be used to stop them.

“You can’t say that!” Trump interjected.

“Well, I just did,” Milley said. “I’m your military adviser. I have to tell you that.” (pp. 160–161)

See what I mean?

And yet, in several public statements, Milley has certainly shown himself to be quite willing to honestly address this country’s awful legacy of racism. I Alone Can Fix It quotes Milley’s June 11 speech before the 2020 graduation at the National Defense University:

“What we are seeing is the long shadow of our original sin in Jamestown four hundred and one years ago, liberated by the Civil War, but not equal in the eyes of the law until one hundred years later in 1965. We are still struggling with racism, and we have much work to do. Racism and discrimination, structural preferences, patterns of mistreatment, unspoken and unconscious bias have no place in America, and they have no place in our Armed Forces.” (p. 186–187)

Milley then apologized for participating in Trump’s notorious photo-op on June 1 when Trump held up a Bible for no apparent reason: “I should not have been there. My presence in that moment, and in that environment, created the perception of the military involved in domestic politics.”

And what is Trump’s takeaway from all this?

A couple of days later, Milley met with Trump in the Oval. He could tell the president was furious. There were other people in the room, but Trump focused on Milley.

“Why did you apologize?” he asked. “Apologies are a sign of weakness.” (p. 187)

By July, Trump was talking about delaying the election. He poll numbers were not looking good, and his pollster tried to explain the problem “Mr. President, just look at the data and you can see that the voters are tired… They’re tired of the chaos. They’re just fatigued. They’re really fatigued.”

“They’re tired? They’re fatigued? They’re fucking fatigued?” he asked his pollster. “Well, I’m fucking fatigued, too.” (p. 234)

It is one of the big mysteries about Donald Trump — a mystery that perhaps a future biographer with the acumen of a Robert Caro might unravel — why he wanted to take on a job for which he’s not suited either intellectually or temperamentally. The details of policy were clearly beyond his comprehesion. Otherwise, we would have had a health plan to replace Obamacare. He seems instead to enjoy the glory and power of being President. The job validates his enormous misshapen ego. Consequently, the possible shame in losing is devastating to him.

Perhaps Trump’s most revealing statement about why he wanted to be President was a comment about Joe Biden:

“I can’t lose to this fucking guy.”

I think it will take more years and much more research to determine the depth of Trump’s attempt to remain in office contrary to the will of the American voters. As I’m writing this, over the past few days we’ve been learning about the role that Assistant Attorney General Jeffrey Clark played in persuading states to overturn the election results. This has led some people to call Trump’s actions an “attempted coup,” and that may be how we shall one day think of this time in our history.

Trump’s attack on the election was multi-pronged. He wanted his Justice Department to indict his enemies. He dreaded the announcement that the Durham Inquiry would not complete before the election, and hence he wouldn’t have evidence against Obama and the Democrats.

Trump began casting doubt on mail-in ballots during the summer of 2020, and he never let up. This was dangerous stuff! Trust in the legitimacy of elections is vital to a functioning democracy. If there is fraud, it must be detected and eliminated. But if there is no fraud, then it is the solemn duty of the loser to gracefully concede.

Ten months after the election, Trump has still not conceded, and at this point, I suspect he never will. That’s unprecedented, and it should sicken anyone who values the institution of democracy.

At times when reading I Alone Can Fix It, we see how Trump’s more extreme tendencies were blocked by adults in the room. Milley seems to have been one of those adults. Bill Barr occupies a more ambiguous role, sometimes countering Trump’s desire to use the Justice Department for political ends, but at other times, not so much. Barr certainly deserves credit for denying that there was any substantial election fraud before he abandoned the sinking ship.

Adults in the room were helpful, but the real danger was the presence of someone in the room who was definitely not an adult, and who was even whackier than Trump. I speak of Rudy Giuliani, of course. When Trump’s legal firm declined pursuing further election fraud claims in court, Giuliani assembled a legal team that included Jenna Ellis (whose book The Legal Basis of a Moral Constitution argued that the United States Constitution was based on Biblical precepts), and Sidney Powell, who eventually spouted conspiracy theories that were even too bizarre for Giuliani and Trump.

Though the Giuliani-Ellis-Powell team dubbed itself “an elite strike force,” it included a lawyer who hadn’t appeared in court since the 1990s; another whose work largely consisted of domestic abuse, traffic court, and religious-liberty cases; and yet another who gained notoriety for promoting conspiracy theories about a “deep state.” Some of them, including their chief strategist, Giuliani, appeared unfamiliar with the legal arguments the team had already made in court filings. (pp. 387 – 388)

As the electoral results were certified and the official affirmation day of January 6 approached, Milley kept receiving intelligence that problems were brewing among the Trump supporters who believed the election was stolen. Trump, of course, was doing everything he could to encourage those beliefs.

Milley told his staff that he believed Trump was stoking unrest, possibly in hopes of an excuse to invoke the Insurrection Act and call out the military…

A student of history, Milley saw Trump as the classic authoritarian leader with nothing to lose. He described to aides that he kept having this stomach-churning feeling that some of the worrisome early stages of twentieth-century fascism in Germany were replaying in twenty-first-century America. He saw parallels between Trump’s rhetoric of election fraud and Adolf Hitler’s insistence to his followers at the Nuremberg rallies that he was both a victim and their savior.

“This is a Reichstag moment,” Milley told aides. “The gospel of the Führer.” (p. 437)

The penultimate chapter of I Alone Can Fix It is entitled “The Insurrection.” I suppose that’s the most accurate term for what happened on January 6. It could also be described as an “attempted coup” or a “race riot,” given the white-supremacist orientation of some of the groups and people involved.

For those expecting to learn that Trump was stunned while watching the television coverage of January 6, and that he suddenly realized what his irresponsible actions had brought down on America, and he proceeded to take a full moral inventory of his life, I’m afraid you’ll be disappointed. There is no moment of awakening, no redemption, and definitely no apologies.

In the closing pages, Leonnig and Rucker describe Trump’s life now:

In the morning hours, he spends time alone in his private quarters watching television and making phone calls to allies and friends. Many days he plays a round of golf at one of his nearby clubs. And in the afternoons, he puts on his suit, applies his makeup, and emerges for meetings with whichever politicians or acolytes have made the pilgrimage to Mar-a-Lago. (p. 515)

But Trump’s evil lives after his Presidency. All over the country, under the guise of “voting integrity,” states are introducing laws to restrict voting, and prevent the catastrophe that Republicans experienced in 2020.

That catastrophe was not voter fraud. No, what Republicans fear most, and what they are now trying to prevent, is too many people voting for Democrats.