Celebrating the Flaubert Bicentennial with “Salammbô”

June 17, 2021

Roscoe, N.Y.

My favorite scene in Orson Welles’ Citizen Kane is an elegant piece of wordless storytelling: It’s opening night at the opera house that Kane has built for Susan Alexander. Starting at 1:16:09 in the movie, we’re on the stage witnessing the frantic last-minute preparations while the orchestra has already begun the opera’s dramatic prelude. The curtain rises, and Susan Alexander begins her opening aria. But quite oddly, the camera itself is rising with the curtain. Soon the stage drifts from view, and we see other suspended backdrops as we ascend into the fly loft. Numerous curtains and ropes pass by as the camera continues to climb. The music becomes fainter, more echoey, until finally the camera comes to rest on two burly stagehands standing on a catwalk, leaning over a rail to watch the action on the stage. By their attentiveness, we understand that they are opera fans as well as opera stagehands. They turn to look at each other, and one of them pinches his nose in a pee-yew gesture.

That’s during the Jed Leland narrative of Citizen Kane. About 15 minutes later, during the Susan Alexander narrative, we see the opening of the opera again. This time, we see the back of Susan Alexander as the curtain rises, and her own view out into the audience. We see a little more of the opening aria, the audience reaction, the gesticulations of Susan’s vocal coach in the prompter box, and soon the music fades to the very end of the opera. With the orchestra’s closing chords, the heroine (as in many operas) collapses and dies.

The music for these opera sequences was composed by the great Bernard Hermann, who began his career in films with scores for Citizen Kane and the marvelous The Devil and Daniel Webster, and later worked with Alfred Hitchcock, including the famous scores to Vertigo, North by Northwest, and Psycho, and concluding his long career with Brian De Palma’s Hitchcockian thrillers Sisters and Obsession and Martin Scorese’s Taxi Driver.

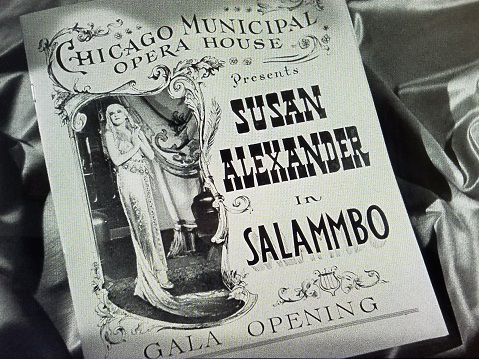

Citizen Kane gives us a brief glimpse of newspaper reviews following this opera debut, from which we learn that the opera is entitled Salammbo. Towards the beginning of the movie we’ve previously seen a poster for it at time 9:20 during the newsreel sequence:

Salammbo is a fictional character created by Gustave Flaubert for his 1862 novel, and Citizen Kane is why I’ve been intrigued by Flaubert’s Salammbô for several decades. Only recently — inspired by the 200th anniversary of Flaubert’s birth — did I actually read it.

Flaubert invented the modern realist novel with the publication of Madame Bovary in 1857. Even more so today, it ranks among the greatest novels ever written.

A lesser novelist would perhaps have followed it up with something similar, or at least in the same universe. Flaubert did not. He was an author who took risks, who continued to challenge himself with difficult goals. Salammbô is instead an historical novel that takes place in and around Carthage in the 3rd century BC. Much research was required. Flaubert claimed to have consulted over 200 books to drench himself in period detail, and he made two long trips to the Middle East and North Africa to familiarize himself with locales where the novel takes place.

The result is nothing like Madame Bovary, but in its attention to detail and often gloriously vivid writing, Salammbô is very recognizably Flaubert.

Salammbô is not an easy read. One problem is that Flaubert tends to maintain an objective distance from his subject over many pages of description, and if what he’s describing is not very interesting, the result can be quite tedious. I personally seem to be particularly incapable of following even the simplest of military maneuvers, and there are many battle scenes in this novel. Yet, Flaubert continues to surprise, and even in the middle of a battle he will introduce a particularly unusual sequence that suddenly rivets the attention. I frequently found myself reading these passages out loud to my wife Deirdre just to savor them again. I will not be able to resist quoting some passages again.

Another problem with Salammbô is the violence. We modern readers might think that we’re inured to fictional violence, but in its relentlessness and detail, the violence of Salammbô is nearly pornographic. Flaubert was apparently an admirer of the writings of de Sade, a tendency that might seem odd for readers of Madame Bovary or Sentimental Education, but not for readers of Salammbô. Even before the cannibalism and the child sacrifices, I found the often grotesque and gruesome violence of Salammbô to be quite shocking. Not content to torture humans, Flaubert goes after animals as well. Early in the novel, after one vivid description, a character asks “What sort of people are these who amuse themselves by crucifying lions!” We might ask the same of the author. And if you have a soft spot in your heart for elephants, this is probably not the novel for you.

Early readers of Salammbô were shocked not only by its violence but also it’s “sensuality", i.e., sex. We are certainly more jaded in that respect, and while there is no explicit sex in the novel, it still pulsates with an exotic erotic shimmer that can be quite breathtaking.

For readers like me who much to our shame have never learned French, a little caution is advised: There are at least four English translations of Salammbô. The first one was by May French Sheldon, published in London and New York in 1885, and available on Google Books. Although seemingly authorized by Flaubert’s heirs, and despite Mrs. Sheldon’s maiden name, her translation was perceived to have some problems. Moreover, she was an American, which meant that the crucial London literary establishment wasn’t hesitant to reject her work.

A rival translation by John S. Chartres was quickly published, also available on Google Books. This one seems to be the standard public-domain translation. For some reason, Chartres decided to use the spelling “Salambo” in the title of the novel and in the text. (Perhaps to distinguish it from the Sheldon translation?) With the title and character spelled more conventionally but without the circumflex over the final letter, this is the translation available on Project Gutenberg, although typically for the lax bibliographic standards of that site, the translator is not identified.

The Chartres translation also seems to show up in several reprints, including this hardcover edition from a publisher who has created its own unique spelling of the title:

A third English translation by a J. W. Matthews was published in 1901, also available on Google Books.

The only modern translation I know of is by A. J. Krailsheimer as published by Penguin in 1977:

Or you might prefer this different (although not entirely dissimilar) cover:

Used copies of the Penguin edition are available on the used-book market, but it does not seem to be actively sold in the U.S. at this time, which means that Salammbô is out of print in this country. All quotations below are from the Krailsheimer translation.

The historical backdrop of Salammbô is the aftermath of the First Punic War (264–241 BC), which saw the defeat of Carthage by Rome. Despite having fought for the losing side, the many mercenaries employed by Carthage still wished to be paid, and this led to a series of battles known as the Mercenary Revolt, which occurred from 241 to 237 BC. The Mercenaries (who Flaubert seemingly interchangeably also refers to as the Barbarians, but not in a pejorative sense) come from a variety of different lands. They are Africans, Greeks, Campanians, Iberians, Etruscans, Samnites, Gauls, and others. Much is made of their different appearances, languages, and customs, making Salammbô possibly the most multicultural novel of the 19th century.

Many of the characters in Salammbô are based on real people, including the two primary Carthaginian generals Hamilcar Barca and Hanno, who Flaubert portrays as obese and leprous:

Strips of cloth, as on a mummy, were wound round his legs, and the flesh bulged out between the crossed material. His stomach overflowed on to the scarlet jacket that covered his thighs: the folds of his neck fell down on his chest like ox’s dewlaps … He looked like some gross idol roughly hewn out of a block of stone; for a pale leprosy, spread all over his body, gave him the appearance of an inert object. … In his hand he held a spatula of aloe for scratching his skin. (ch. 2)

Among the mercenaries are also real historical figures, most notably the Libyan leader Mâtho, often accompanied and assisted by his Greek slave Spendius.

The major fictional character is Salammbô herself, the daughter of Hamilcar. Her first appearance is stunning:

Her hair, powdered with mauve sand, was piled up like a tower in the style of the Canaanite virgins and made her look taller. Ropes of pearls fastened to her temples fell to the corners of her mouth, rose red like a half-open pomegranate. On her breast clustered luminous stones iridescent as lamprey’s scales. Her arms, adorned with diamonds were left bare outside a sleeveless tunic, spangled with red flowers on a dead black background. Between her ankles she wore a golden chain to control her pace, and her great, dark purple mantle, cut from some unknown material, trailed a broad wake behind her with every step she took.

From time to time the priests plucked muffled chords on their lyres, and in the intervals of the music could be heard the faint sound of her golden chain and the regular clacking of her papyrus sandals. (ch. 1)

This is during a huge feast that Carthage prepares for the Mercenaries that opens the novel. It’s an attempt to appease them but it’s clearly no substitute for hard cash. Salammbô speaks to the soldiers in their own tongues, sings to them accompanied by her lyre, and pours Mâtho some wine. Meaningful glances are exchanged. A Gaul ribs Mâtho that “with us when a woman gives a soldier a drink, she is offering him her bed.”

But not so. Salammbô is a virgin priestess of the goddess Tanit, with her own spiritual teacher and advisor, the eunuch Schahabarim. Although Mâtho brags that he has known women before, his brief encounter with Salammbô has affected him like nothing else:

Am I a child? … Do you think their faces and their songs still touch me? We had women to sweep out our stables in Drepanum. I have had them in the middle of attacks, under ceilings that were crumbling and while the catapult was still vibrating! But that one, Spendius, that one! (ch. 2)

Flaubert interweaves the battles of the Mercenary Revolt with this quasi-affair between Mâtho and Salammbô, but unfortunately with much more emphasis on the former. Another important plot point involves a veil associated with the goddess Tanit. Spendius tells Mâtho: “Master, in Tanit’s sanctuary there is a mysterious veil, fallen from the heavens, which covers the Goddess.” (ch. 5)

This veil (an object that Flaubert invented) is called the zaïmph. No one is supposed to touch it, let alone see it, but Mâtho and Spendius decide to steal it, seemingly in an attempt to desecrate the religion of Carthage, or perhaps because Mâtho is so obsessed with Salammbô that he thinks he actually hates her.

In the most magical sequence of the novel, Mâtho and Spendius enter Cathage through its aqueduct, the existence of which Flaubert also invented. Their trip proceeds like a half-waking hallucinatory dream:

Mâtho was sitting in the heated atmosphere bearing down on him from the cedar partitions. All these symbols of fecundation, these perfumes, these sparkling lights, these breaths oppressed him. Through the dazzling of the mysteries he thought of Salammbo. She became confused with the Goddess herself, and his love came out all the stronger, like the large lotus flowers blooming on the watery depths.

…

Then a dazzling light made them drop their eyes. All around them they saw an infinite number of beasts, lean, panting, brandishing their claws, and mixed on top of the other in mysterious and frightening confusion. Serpents had feet, bulls wings, man-headed fish were eating fruit, flowers were blooming in crocodiles’ jaws, and elephants with raised trunks passed proud as eagles through blue sky. Their incomplete or multiple limbs were swollen by their terrible exertions. As they put out their tongues they looked as though they were trying to force out their souls; and every shape was to be found there, as if a seed pod had burst in a sudden explosion and emptied itself over the walls of the room. (ch. 5)

In this dangerous escapade, they even encounter the sleeping Salammbô herself, leading to one of Flaubert’s most achingly beautiful passages:

She was sleeping with one hand under her cheek and the other arm straight out. The flowing curls of her hair spread round her so abundantly that she looked as though she were lying on black feathers, and her wide, white tunic lay in softly curving folds down to her feet, moulded to the shape of her body. Her eyes were just visible beneath her half-closed lids. The bed-curtains, hanging straight down, enveloped her in a bluish penumbra, and as she breathed, the movement stirred the cords so that she seemed to sway in the air. A large mosquito buzzed. (ch. 5)

Back in the Mercenary’s camp with the zaïmph, Mâtho fondles the veil with the consolation that “the Goddess’s vesture depended on Solammbo, and a part of her soul floated over it more subtly than a breath; and he fingered it, smelled it, plunged his face into it, kissed it to give himself the illusion that he could believe himself beside her.” (ch. 6)

The absence of the zaïmph seems to adversely affect the Cathaginians in the war with the Mercenaries, and Salammbô’s spiritual advisor Schahabarim wants her to get it back. His plan is for her to go into the Mercenary camp and confront Mâtho himself. But Salammbô does not understand exactly how this will work.

“You will be alone with him.”

“So?” she said.

“Alone, in his tent.”

“Well?”

Schahabarim bit his lips. He looked for some phrase, a way round.

“If you are to die, it will be later,” he said, “later! Do not be afraid! And whatever he tries, do not call out! You will be humble, do you understand, and submit to his desire, which is the order of heaven!”

“But the veil?”

“The Gods will see to it,” Schahabarim replied.

Salammbô’s slave Tanach helps get her ready for this task:

Tanach returned to her side, and when she had arranged two candelabras, whose lights burned in crystal balls filled with water, she stained the inside of Salammbo’s hands with lausonia, put vermilion on her cheeks, and antimony on her eyelids, and drew out her eyebrows with a mixture of gum, musk, ebony, and squashed flies’ feet. (ch. 10)

Well, of course. If you want to highlight your eyebrows, what would work better than insect parts?

Salammbô’s appearance naturally affects Mâtho as intended:

Mâtho did not hear; he gazed at her and for him her clothes fused with her body. The shimmer of the material, like the splendour of her skin, was something special and peculiar to her. Her eyes and her diamonds flashed; her polished nails were a continuation of the fine jewels on her fingers; the two clasps of her tunic raised her breasts a little and brought them closer together, and in his imagination he was lost in the narrow cleft between them, down which hung a thread holding an emerald plaque, which could be seen lower down under the violet gauze. For earrings she had two little sapphire scales holding a hollow pearl filled with liquid perfume. From holes in the pearl there fell from time to time a tiny drop which wet her bare shoulder as it fell. Mâtho watched it fall. (ch. 11)

Remember in Chapter 1 when Salammbô was described as wearing between her ankles “a golden chain to control her pace”? Perhaps that chain has a symbolic function as well.

A limpness came over Salammbo and she lost all consciousness of herself. Something both intimate and superior, an order from the Gods, forced her to give herself up to it; clouds lifted her up and as she collapsed she fell back among the lions’ fur on the bed. Mâtho seized her heels, the golden chain snapped, and as the two ends flew off they struck the canvas like two vipers recoiling. The zaïmph fell down, covered her; she saw Mâtho’s face bending over her breast. (ch. 11)

That is as sexually explicit as Flaubert gets in this novel, but you might need a cold shower regardless.

In my refusal to quote any of the very violent passages, I’m afraid that I’ve made Salammbô sound more like a chick flick than a guy movie. Unfortunately, Salammbô herself is not as present in the novel as most of us would prefer. Perhaps that is the main reason why Salammbô is not Madame Bovary. It seems that Flaubert was clearly aware that the novel wasn’t quite what he might have intended. He said himself about Salammbô that “the pedestal is too big for the statue,” and that the character of Salammbô needed another hundred pages. That would have provided a proper aesthetic and ethical balance to the amorality of the violence.

What Flaubert never said was “Salammbô, c’est moi.”

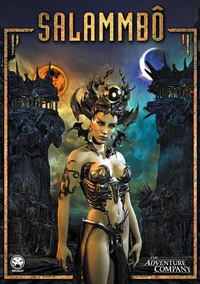

As the Wikipedia article demonstrates, Salammbô has had quite a cultural impact — from paintings to operas to movies to graphic novels to video games:

There have been at least five operas — including unfinished works by Mussorgsky and Rachmaninoff — but I suspect that the closest most of us will get to a Salammbô opera is Bernard Hermann’s music for Citizen Kane. I always assumed that Hermann composed music for the beginning of the opera, and music for the end, and I was astonished to learn that these two excerpts are part of the same aria! It was a favorite concert piece of Kiri Te Kanawa, and here it is sung by Russian soprano Venera Gimadieva:

The text is not from Flaubert. It’s apparently by John Houseman, who worked with Orson Welles in his early days.

Heard in its entirety, Bernard Hermann’s “Salammbo’s Aria” is structurally quite bizarre, seemingly starting at the very beginning of the opera, and ending with the finale in just four minutes.

In its own way, Salammbo’s aria is as perversely unbalanced as the novel itself.