Reading “Wollstonecraft: Philosophy, Passion, and Politics”

March 8, 2021

Sayreville, New Jersey

A woman who should have been President famously said “human rights are women’s rights and women’s rights are human rights, once and for all.” The truth of this is quite self-evident, so it’s surprising how many politicians and others can’t bring themselves to agree, or even to identify human rights as the United States’ foundational ideal.

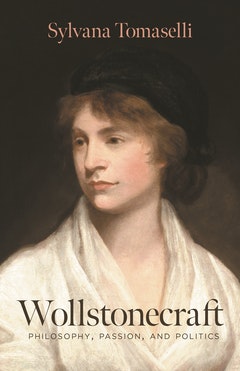

Mary Wollstonecraft is a feminist icon, best remembered for A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, now regarded as an essential early text on the subject. But restricting our knowledge of Wollstonecraft to this one book is inherently limiting, for Wollstonecraft viewed women’s rights as part of a much larger spectrum of human rights. In her book Wollstonecraft: Philosophy, Passion, and Politics (Princeton University Press, 2021), Cambridge historian Sylvana Tomaselli wishes to broaden our understanding of Wollstonecraft by considering her many other writings, in their panoramic (and sometimes self-contradictory) totality.

Wollstonecraft: Philosophy, Passion, and Politics is not a biography. (For a biographical background, Tomaselli recommends recent books by Janet Todd, Lyndall Gordon, and Charlotte Gordon.) It is instead an intellectual portrait illuminated only when necessary by the biographical. For that reason, it is not arranged chronologically but by various topics grouped into just four chapters, an organization Tomaselli says was patterned after Wollstonecraft’s first book, Thoughts on the Education of Daughters.

Chapter 1 is quite a surprise: a collection of what Wollstonecraft “liked and loved,” including her appreciation of the theater (with an emphasis on Shakespeare), painting (Blake and Henry Fuseli, the latter with whom she was “wildly besotted"), music (Purcell and Handel), poetry (did Wollstonecraft’s travel writings inspire Coleridge’s “Kubla Khan"?), nature, reading, and the more personal loves of her life.

This chapter won me over. As someone who in particular enjoys the music of earlier centuries, I am often curious how now-famous people of those eras reacted to the music of their time. It’s perhaps not surprising that Mary Wollstonecraft liked Handel, but it’s even more interesting to see her quoting texts from Messiah and Judas Maccabaeus, and writing a long glowing review of Charles Burney’s four-volume History of Music.

Through Wollstonecraft’s aesthetics, we begin to get a feel for her moral foundations, and the connection to her religious inclinations.

Wollstonecraft writes of poetry and its effects, as she had of music, within the framework of contemplation of the divine creation. Indeed she thought of poety, in what one might call its purity, when a most direct reflection of sensory impressions of nature or feelings, as devotional. (p. 39)

It is in the second chapter ("Who Are We? What Are We Made Of?") where we begin to explore Wollstonecraft’s commitment to human rights, which arose from a core belief in the unity of humanity. Although people of different cultures and races seem to be different, Wollstonecraft wrote, “yet there is a degree of uniformity in their variety which silently affirms that they proceed from the same source.” (p. 67) (This was still a matter of dispute among scientists 150 years later, as I discovered from reading Darwin’s Sacred Cause: How a Hatred of Slavery Shaped Darwin’s Views on Human Evolution. Darwin was a “unitarist,” believing like Wollstonecraft that the human race had a single source, as opposed to the “pluralists,” who believed the races were created or emerged separately.)

From her conviction of the unity of humanity came Wollstonecraft’s opposition to slavery, and eventually her opposition to many of the ways in which people are ranked or placed in hierarchies or have power over one another, as Tomaselli lists them: “privilege, wealth, legal and political rights, and education.” (p. 71) Wollstonecraft had an Enlightenment-era confidence in human perfectability following a revolution in morals, which (despite some of the accompanying horrors) she saw as a hope in the French Revolution. The principles in the Déclaration des droits de l’homme et du citoyen de 1789 she considered to be self-evident truths.

The inciting incident for Mary Wollstonecraft’s major works was the publication of Edmund Burke’s Reflections on the Revolution in France on 2 November 1790. Wollstonecraft was not the only person enraged by Burke’s ridiculing of the concept of the rights of man and his affirmation that “We fear God; we look up with awe to kings, with affection to parliaments, with duty to magistrates, with reverence to priests, and with respect to nobility.”

The most famous response to Burke was Thomas Paine’s Rights of Man, but Wollstonecraft was first out of the gate with her book, published anonymously on 29 November with the full title A Vindication of the Rights of Men, in a Letter to the Right Honourable Edmund Burke; Occasioned by His Reflections on the Revolution in France. The word Vindication she took from an earlier book by Burke to remind him that he had once held more humane views. Tomaselli observes:

To the degree that hers is a vindication at all, it is a vindication of itself, of the need to challenge Burke and all he appeared to be standing for on the publication of the Reflections. It is an attack, a vilification of Burke, as a politician and theorist; it is an attack that ventures beyond his Reflections, on what Wollstonecraft takes to be his conceptual framework and assumptions, on his style, and his own attacks, and more. It questions his analytical and moral competence, his independence, morality, and patriotism. It questions his very self, and most significantly, his masculinity. (p. 144)

Yes, Wollstonecraft was not above wielding what we would now call “gendered language” to demonstrate that Burke himself had those feminine characteristics he had sniffed at in earlier works. As Tomaselli puts it, “she garlanded Burke with the terms of fickle feminity.” (p. 148) Tomaselli writes:

From its earliest stage, Burke believed that what was taking place in France was not merely a political revolution ... but a civilizational one with neither prededent nor equal, one that would entirely transform every aspect of European societies, down to the relations between the sexes. Wollstonecraft thought that this was precisely what needed to happen for the revolution to achieve what she took to be its central aim, liberty. (p 144)

Wollstonecraft’s A Vindication of the Rights of Woman: with Strictures on Political and Moral Subjects came in 1792, possibly using a similar title as the first Vindication as a type of branding. What arises most powerfullly from Tomaselli’s analysis of the two Vindication books is the positioning of women’s rights within a much broader social critique that encompassed education, inheritance, social hierarchies, sexual relations, and economic inequality.

Many of these themes are again explored in Wollstonecraft’s 1794 book An Historical and Moral View of the French Revolution; and the Effect It Has Produced in Europe, in which she writes (as Tomaselli quotes her):

Nature having made men unequal, by giving stronger bodily and mental powers to one than to another, the end [i.e., the objective] of government ought to be, to destroy this inequality by protecting the weak. Instead of which, it has always leaned the opposite side, wearing itself out by disregarding the first principle of its organization.” (p. 163)

In the last short chapter of Sylvana Tomaselli’s book, entitled “A Life Unifinished,” she suggests that with more time, Mary Wollstonecraft might have been able to fashion many of her ideas into a book less dependent on the immediate events surrounding her. But in September 1797, she died following the birth of a daughter, leaving behind an unfinished novel Maria: or, The Wrongs of Woman, featuring a narrator who is writing from an asylum that her husband has imprisoned her in.

Twenty years later, Mary Wollstonecraft’s daughter, also named Mary, published her own quite different novel: Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus.