Reading “The Man in the Red Coat”

February 25, 2020

Sayreville, New Jersey

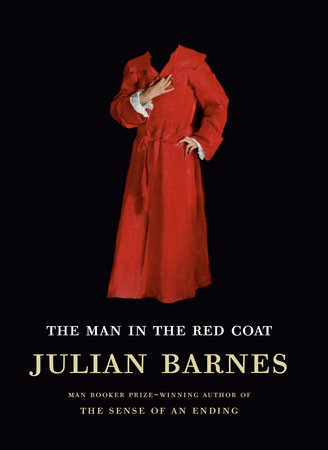

In September 2015, Deirdre and I went to an exhibit at the Metropolitan Museum entitled “John Singer Sargent: Portraits of Artists and Friends.” Among the many startling paintings was a life-size bearded man in a full-length crimson robe. His long spindly fingers seem to hold the robe shut, and an ornate slipper peaks out, two of the many details that cause the painting to exude a vivid sexual power.

“Dr. Pozzi at Home,” I read from the card next to the painting. “He was a pioneer in the field of modern gynecology.”

“I wonder if he treated hysteria,” Deirdre pondered.

“Or caused it,” said a woman standing next to us.

Earlier that year, novelist Julian Barnes saw the same exhibit at the National Portrait Gallery in London. Barnes had never heard of Dr. Pozzi either, but he evidently wanted to know more, and the result is the fascinating book The Man in the Red Coat (Knopf, 2020), an unconventional biography that blossoms into an enthralling panoramic view of fin de siècle Europe and Belle Époque Paris.

Samuel Jean Pozzi, born in 1846, came from a family of Italian Protestants who had moved to Switzerland and then France. His mother died when he was 10 but his father then married an Englishwoman, so that Pozzi grew up speaking both French and English despite the Italian surname. He specialized in surgery rather than the type of treatment for hysteria that my wife and I imagined. His doctoral thesis was entitled “The Value of Hysterectomy in Treating Fibroid Tumours of the Uterus.” John Singer Sargent’s portrait dates from 1881, when Dr. Pozzi was 35 and had just become a hospital surgeon.

Beginning with his language fluency, Dr. Pozzi was by nature a cosmopolitan — politically progressive, a supporter of Alfred Dreyfus, and a scientific atheist. He co-translated Charles Darwin’s The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals, and studied new techniques for surgery and sterilization. Pozzi was familiar with the pioneering work done by Florence Nightingale during the Crimean War, and on a trip to Edinburgh in 1876, he learned about sterilization techniques direct from Joseph Lister, and then brought those procedures back to Paris. Eventually he would write a two-volume, treatise Traité de gynécologie clinique et opératoire with 1,100-pages and over 500 illustrations, that remained the standard gynecological textbook in France into the 1930s.

But this is not a medical biography. Barnes is mostly interested in colorful people and personalities. Although Dr. Pozzi was married, the marriage was not a happy one, and Dr. Pozzi compensated with numerous love affairs, some with his celebrity female patients. Princess Alice of Monaco called him “disgustingly handsome” and some women referred to him by the title of the Molière play L’Amour médecin, or Dr. Love.

Actress Sarah Bernhardt — with whom Pozzi had a love affair and an extended friendship afterwards — instead called him “Doctor Dieu.” He once extracted an ovarian cyst “the size of the head of a fourteen-year-old” from the actress. This was a time, Barnes reminds us, when you could easily die of appendicitis, or just as easily from an appendectomy.

What makes The Man in the Red Coat most entertaining is the long parade of writers, painters, celebrities, and dandies — both famous and not so famous — who make extended or brief appearances. Julian Barnes never met a fascinating digression he didn’t like, or a name he is unwilling to drop. John Singer Sargent, Henry James, Oscar Wilde, James Abbott Whistler, and Alfred Dreyfus are some of the more well known, but the lesser known are just as dazzling.

Dr. Pozzi was a friend of the Proust family: “he invited the young Marcel to his first ‘dinner in town’ at the place Vendôme, and later helped him avoid military service; while Marcel’s younger brother Robert was Pozzi’s assistant at the Broca Hospital from 1904 to 1914.” Robert Proust carried out the first successful prostatectomy in France, a surgery that for many years was called a “proustatectomy” in his honor.

Most surprising in The Man in the Red Coat are the duels. While the English had for the most part given up settling disputes by dueling, the French had not. Throughout The Man in the Red Coat, people are getting into squabbles and soon find themselves shooting at each other or poking at each other with swords. The dispute need not be in any way consequential. One duel that Barnes describes is between two men who “had fallen out backstage at the theatre about exactly how thin Sarah Bernhardt had been when she played the role of Hamlet.”

But duels are not the only way people get shot in this book. Frequently, men and women who have a gripe with someone will express their displeasure with a handgun and then quietly wait for the police to show up. When an anti-Semitic journalist shoots Alfred Dreyfus in the arm and hand during the ceremony to inter Emile Zola in 1908, Dr. Pozzi is there to administer first aid.

When we last see him, Dr. Pozzi is serving as a surgeon in the Great War, and profiled in the New York Herald Tribune as “the most eminent surgeon in France.” The Man in the Red Coat is copiously illustrated, and even in the photograph of the 70-year-old Pozzi in his military uniform, we still see a glimpse of the sexy beast that John Singer Sargent painted.

More than once, Julian Barnes quotes Dr. Pozzi as saying that “chauvinism is one of the forms of ignorance.” This is reflected directly by his assimilation of medical knowledge acquired from around the world. But he also seems to have gotten along with everybody — at least everyone outside his immediate family — and shared his knowledge with scientific generosity.

In an Author’s Note at the end, Julian Barnes contrasts Dr. Pozzi’s cosmopolitanism with “Britain’s deluded, masochistic departure from the European Union” that quickly snaps us out of this long-ago time and drags us back into the real world.