Falling into the “Little Women” Vortex

December 30, 2019

Sayreville, New Jersey

A few weeks ago Esther Schindler posted one of her famously irresistible Facebook queries: “What book have you tried to read several times, but given up on for one reason or another -- and you still intend to give it another try?”

I had to fess up and respond: Little Women.

Last year, Louisa May Alcott’s novel celebrated its 150th anniversary, and it was on my mind after I read reviews in both The New Republic and The Atlantic of the book Meg, Jo, Beth, Amy: The Story of Little Women and Why It Still Matters by Anne Boyd Rioux. I was intrigued about the circumstances and controversies that still surround Little Women, and not for the first time, I vowed to read it, yet I did not.

Just a few days before Esther’s post, I had once again decided to finally read Little Women in preparation for the new movie adaptation written and directed by Greta Gerwig, whose career I’ve been following with ever-increasing joy since her days as a mumblecore goddess in movies like Hannah Takes the Stairs. But like all the previous times when I opened the book in a bookstore, or brought up an ebook, the opening dialogue stopped me dead:

“Christmas won’t be Christmas without any presents,” grumbled Jo, lying on the rug.

“It’s so dreadful to be poor!” sighed Meg, looking down at her old dress.

“I don’t think it’s fair for some girls to have lots of pretty things, and other girls nothing at all,” added little Amy, with an injured sniff.

“We’ve got father and mother, and each other, anyhow,” said Beth, contentedly, from her corner.

It’s not that I have objections to stories about sisters. I am very fond of the Dashwoods and the Bennets, and although the four women of the TV series Sex and the City and Girls were not sisters in the biological sense, I enjoyed their interactions, travails, and insights.

I think my problem with the opening of Little Women was the way that Louisa May Alcott introduces all four sisters right up front, and gives each character a turn as if she were dealing a hand of poker. I knew I’d have to devise some mnemonic to keep them all straight, and I might even need to determine how they corresponded to classical quadripartite divisions of personality, such as the four temperaments, or the four suits of Tarot cards, or the four houses of Hogwarts.

In other words, Little Women would be way too much work. Yet, the public confession that I had never read the book unnerved me, and as soon as I left my response to Esther's post, I realized that it had to be followed by a public atonement.

If you’ll be reading Little Women for the first time or revisiting it, I do recommend Anne Boyd Rioux’s book. Much of what I know about the novel outside of its pages I learned from Professor Rioux, or by springboarding from her footnotes. This is a wonderful overview that encompasses the life of Louisa May Alcott; the writing of her frequently autobiographical novel; the various stage, movie, and television adaptations; and how the book has been read over the past 150 years. As one might expect, the enlightening wave of feminist scholarship that emerged in the 1970s confronted the novel anew, and developed new appreciations and new criticisms. That reevaluation is still going on.

Louisa May Alcott was a fast writer. She wrote Little Women or, Meg, Jo, Beth and Amy between May and July 1868. She reviewed page proofs in August and the book was published in Boston on September 30. While many of life's activities have sped up over the past century and a half, book publishing is now usually considerably slower.

I couldn’t find an 1868 first edition of Little Women on Google Book Search — perhaps the early copies obtained by libraries were quickly read to ribbons — but the Internet Archive has one. The first edition had several illustrations by Abigail May Alcott, Louisa’s youngest sister, who became the character of Amy in the novel. The book covers just over a year in the life of the four sisters beginning on Christmas Eve 1861 in the first year of the American Civil War, and it famously ends with the four sisters gathered together:

So grouped the curtain falls upon Meg, Jo, Beth, and Amy. Whether it ever rises again, depends upon the reception given to the first act of the domestic drama, called “Little Women.”

The reception was quite good. The book sold 2,000 copies in two weeks, and Miss Alcott was pressed upon to continue the story, which she also managed very quickly. She began writing the sequel in November 1868, finished in January 1869, and it was published in April. At first they didn’t know what to call the sequel, but they gave it the same title as the first book with the title page indicating Part Second. Illustrations were by Hammatt Billings. Readers were accustomed at the time to novels published in multiple volumes, so the concept was not unusual.

In England, however, the sequel was published as Good Wives, and to this day, many British readers call it by that name and consider it to be a separate novel. Good Wives is still often published separately, as in this edition on Amazon UK. "I like Little Women but I don't care much for Good Wives," British readers have been known to say.

Louisa May Alcott followed Little Women with the sequels Little Men (1871) and Jo’s Boys (1886). In the U.S. these are considered a trilogy of sorts, such as in this Library of America edition. In the U.K. the novels form a tetralogy such as in this British edition called The Complete Little Women.

In 1880, the Boston publisher Roberts Brothers combined the first and second parts of Little Women into one volume. The two halves were still identified as “Part First” and “Part Second” but the chapters were numbered consecutively, and the text was accompanied by over 200 new illustrations by Frank T. Merrill.

The text was also altered somewhat, apparently to tone down some of the undecorous or slangy language. As a result, the 1880 version really constitutes a second edition, although it was not identified as such. For many decades, this second edition was the one most frequently published, but in recent years some publishers (such as Penguin and W. W. Norton) have gone back to the first edition as closer to Alcott's intentions. The Norton Critical Edition (which scrupulously reproduces the original edition) lists 23 pages of textual variants in the second edition. The first change was in the third paragraph of the first chapter (see above), where “lots of pretty things” was changed to “plenty of pretty things.” In the fourth paragraph, the word "anyhow" was eliminated. Some of the more significant changes just in the first chapter are:

- “I’m sure we grub hard enough” to “I’m sure we work hard enough”

- “I ain’t” to “I’m not”

- “I am a selfish pig!” to “I am a selfish girl!”

They don’t seem very significant by themselves but cumulatively they tend to smooth down some of the rougher edges.

The copy of Little Women on gutenberg.org is the second edition, and another copy is also the second edition, but the HTML, EPUB, and Kindle versions of this latter one include the 200-odd illustrations from that edition.

My original fear that the four March sisters would be too many to keep straight was, of course, ridiculous. I quickly determined that the order of their increasing ages is the same as the alphabetical order of their names, and in the first chapter, I flagged a long paragraph that revealed their ages and dispositions, and then I barely referred to it. Louisa May Alcott cleverly reveals important aspects of their personalities in the opening four lines: Josephine or Jo is lying on the floor because she’s a tomboy. Meg likes nice things, Amy is vain and selfish, and Beth is content with her lot in life. She's in the corner because she's shy.

It is well known that Miss Alcott drew from her life and family to write Little Women. Although the setting is not explicitly identified, it is very much like Concord, Massachusetts where the Alcotts lived. The big house next door where the Lawrence grandfather and grandson reside is based on the home of Ralph Waldo Emerson, whose library Louisa was able to raid. The Alcotts also knew the Hawthornes and Henry David Thoreau.

The timeframe of Little Women does not coincide with Louisa May Alcott's reality, however. At the beginning of Part 1, the four girls are ages 12 through 16. The fictional Jo is 15 years old on Christmas Eve 1861, which suggests that she would have been born in 1846. Louisa May Alcott was born in 1832. She was not a teenager during the Civil War, but instead in her late 20s and early 30s.

Part 2 of Little Women jumps three years after the close of Part 1. The war is over, Meg’s wedding (Chapter 25) takes place in June 1866, but then the timeframe gets vaguer. In Chapter 43, Jo is “[a]lmost twenty-five, and nothing to show for it,” and in the final pages of Part 2, Jo is “over thirty” (which was changed in the 2nd edition to just “thirty”) which dates the conclusion of the novel at around 1876, some years in the future from when it was published!

For much of Part 1, the March father is serving as a chaplain in the Union army, so the mother (Marmee) is effectively a single parent raising four girls. The household is initially a community of women that only gradually allows men and boys into the sanctum, and then only on the women’s terms. Although the March family is on the poor end of the economic spectrum when compared with people they know and socialize with, they do have a maid named Hannah. They are certainly not as poor as those they often help with their charity work, such as the Hummels, the German immigrant family who play a crucial role in the novel.

The Alcott family was much more demonstrably progressive than the Marches. The Alcott parents, Bronson and Abigail, were both antislavery activists and women’s rights advocates. Prior to the Civil War, they harbored fugitive slaves, and hosted visits by Frederick Douglass and John Brown’s daughters. Bronson was a transcendentalist philosopher and education reformer, but he was not a good provider for his family. A school that he started was already controversial due to his teaching philosophy, but it had to be shut down entirely following a big commotion when he accepted a black pupil. Bronson was often away from his home on speaking tours that made little money.

Out of economic necessity, the two oldest Alcott daughters began working early to help support the family. Among other types of work, Louisa was able to earn some money writing. During the Civil War, it wasn’t Bronson Alcott who was away, but Louisa herself. In December 1862, at the age of 30, she briefly served as a nurse at the Union Hotel Hospital in Georgetown, but she soon caught typhoid, had to be sent back to Concord, and almost died.

The American philosophical movement of transcendentalism is closely associated with religious beliefs of Unitarianism, but neither doctrine is mentioned in Little Women. They were perhaps a bit too controversial for the book’s prospective audience. Yet, it is interesting that the Marches don’t seem to go to church, even on Christmas. Louisa had a reputation as being “grahamish,” an obsolete word referring to the vegetarianism of Sylvester Graham, the inventor of the Graham cracker. A modern-day equivalent would be to refer to Louisa as a “granola girl.” This is also an area Little Women avoids. (Rioux, p. 29)

Louisa May Alcott was known as Lou, Lu, or Louie among her family, just as Josephine March is known as Jo. Although the word “tomboy” is used only once in the novel, many other references give her what we would now call a gender-nonconforming ambiance. For example, with her father gone, Jo thinks of herself as “the man of the family,” (ch. 1) and it’s fun to find other startling statements of Jo’s, such as “I just wish I could marry Meg myself, and keep her in the family.” (ch. 20) These tendencies of Jo’s safely fade away as she grows older.

The boy next door is named Theodore Lawrence, but the other kids made fun of him at school by calling him Dora. The implication is clear: In the slang of the time, they might also have called him a “milksop” or simply a “sop.” He insists that they call him Laurie rather than Dora, which doesn’t quite solve the problem. Laurie plays the piano and speaks French and his best friends become the March sisters, so he starts out by being somewhat gender ambiguous as well.

The first dozen or so chapters of Little Women felt episodic and unconnected to me, as if Alcott was trying to find her way with the material. But then the sisters start talking about their futures, and Jo says “I think I shall write books, and get rich and famous; that would suit me, so that is my favorite dream.” (ch. 13) Besides being an archetypal tomboy, Jo has also been the hero of voracious readers and aspiring young writers.

Lying back on the sofa, she read the manuscript carefully through, making dashes here and there, and putting in many exclamation points, which looked like little balloons; then she tied it up with a smart red ribbon, and sat a minute looking at it with a sober, wistful expression, which plainly showed how earnest her work had been. (ch. 14)

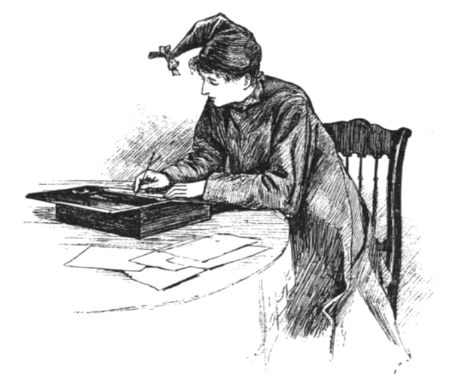

Here’s how she’s portrayed in the 1880 edition:

Notice the completed pages piling up. Jo soon begins to have little stories published in the local papers.

The remainder of Part 1 than begins coming together as a real novel. The family gets a telegram that their father has become ill, and Marmee needs to go be with him. Jo famously has her hair cut off to sell to a wig maker for fast cash. This is another example of gender nonconformity that jumps out to the modern reader.

Jo took off her bonnet, and a general outcry arose, for all her abundant hair was cut short.

“Your hair! Your beautiful hair!” “Oh, Jo, how could you? Your one beauty,” …

Jo assumed an indifferent air…. “It will do my brains good to have that mop taken off; my head feels deliciously light and cool, and the barber said I could soon have a curly crop, which will be boyish, becoming, and easy to keep in order. I’m satisfied; so please take the money, and let’s have supper.”

When Marmee is away, however, one of the Hummel children dies of scarlet fever. Beth has been helping the family, so she contracts it as well, and the meshing of these two plots becomes very disturbing. Why is Beth sick when Marmee’s not there to comfort her? The family has gone from a single-parent household to a no-parent household in a time of greatest crisis. Dramatically, everything that happens in connection with Mr. March’s illness and Beth’s illness comes together in a very rewarding way.

In Part 2, we skip ahead three years. “The war is over, and Mr. March safely at home, busy with his books and the small parish which found in him a minister by nature as by grace.” (He is still largely absent from the action, and it wouldn't be much of a change to the book if Marmee were a widow.) Laurie’s tutor, John Brook, also “did his duty manfully for a year, got wounded, was sent home, and not allowed to return.” (ch. 24) But in a novel whose first half takes place during the Civil War, how we yearn to hear much more about it!

In Chapter 27, “Literary Lessons,” we follow Jo’s progress becoming a better writer, a financially more successful writer, and even a more disillusioned writer. She’s trying to move beyond the little columns and stories she’s been writing for the periodicals, and she’s even working on a novel. Here she is in the 1880 edition with a traditional writing box used to hold paper, pens, and ink:

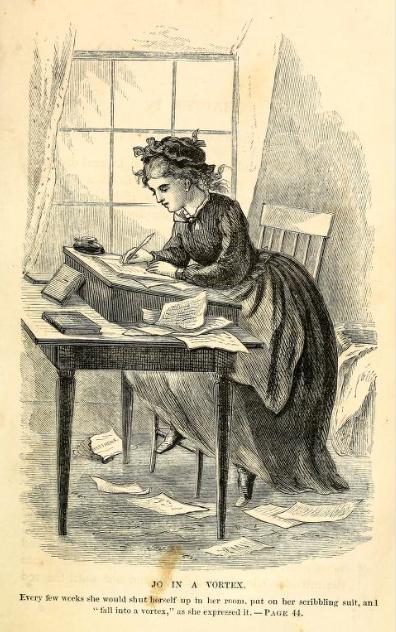

Every few weeks she would shut herself up in her room, put on her scribbling suit, and “fall into the vortex,” as she expressed it, writing away at her novel with all her heart and soul, for till that was finished she could find no peace. Her “scribbling suit” consisted of a black pinafore on which she could wipe her pen at will, and a cap of the same material, adorned with a cheerful red bow, into which she bundled her hair when the decks were cleared for action. This cap was a beacon to the inquiring eyes of her family, who, during these periods, kept their distance, merely popping in their heads semi-occasionally, to ask, with interest, “Does genius burn, Jo?” They did not always venture even to ask this question, but took an observation of the cap, and judged accordingly. If this expressive article of dress was drawn low upon the forehead, it was a sign that hard work was going on; in exciting moments it was pushed rakishly askew, and when despair seized the author it was plucked wholly off, and cast upon the floor. At such times the intruder silently withdrew; and not until the red bow was seen gaily erect upon the gifted brow, did any one dare address Jo.

The following illustration from the 1869 edition with papers flying around the room is more evocative of the flurry of activity:

To continue:

She did not think herself a genius by any means; but when the writing fit came on, she gave herself up to it with entire abandon, and led a blissful life, unconscious of want, care, or bad weather, while she sat safe and happy in an imaginary world, full of friends almost as real and dear to her as any in the flesh. Sleep forsook her eyes, meals stood untasted, day and night were all too short to enjoy the happiness which blessed her only at such times, and made these hours worth living, even if they bore no other fruit. The divine afflatus usually lasted a week or two, and then she emerged from her “vortex” hungry, sleepy, cross, or despondent.

Such are the romantic images that have been inspiring young writers for 150 years! In real life, Louisa would sometimes make herself sick with this binge writing.

I must admit that I never wrote like this. Even in my 20s when I was writing crappy fiction, I wrote mostly disconnected phrases that I would then have to patch together into sentences and paragraphs. Before word processing, my drafts resembled diagrams of conspiratorial connections. I welcomed adding word-processing software to this process, for it let me move and stitch together words, phrases, and sentences with much greater ease.

In real life, by 1860 the most prestigious publication that Louisa May Alcott had cracked was the Atlantic Monthly, a magazine that still exists as The Atlantic but which no longer publishes fiction. “Love and Self-Love,” which appeared in the March 1860 issue (available on Google Books and The Atlantic archives), is an eerily disturbing first-person narrative of a socially isolated man in his thirties who feels obligated to marry a girl half his age when her guardian dies. He describes himself as a “cold, selfish man, often gloomy, often stern,” and in his confusion over how to properly love his wife, he reestablishes a relationship with an old flame. This does not help.

Alcott’s story “A Modern Cinderella: Or, The Little Old Shoe” appeared in the October 1860 issue (Google Books and The Atlantic archives). This story is also reprinted in the Norton Critical Edition of Little Women because it features three sisters: Di is a reader and a writer (who bemoans “if I were only a man”), and Laura is a painter, and the eldest Nan ends up doing much of the housework. They are motherless (no Marmee) but their father is a rather theoretical farmer who plants his seeds based on “the first proposition in Euclid,” which describes how to construct an equilateral triangle. The love interest for Nan is John Lord, and after he leaves them one day with a promise to return as a successful man, Nan throws a shoe after him for good luck. (The reference is to Chapter 10 of David Copperfield.) He picks it up and keeps it, much like the fetishistic glove of Meg’s that John Brooke keeps in Little Women. The title of the story suggests how this will turn out. (If you page backwards from "A Modern Cinderella" in The Atlantic Monthly, you'll discover an article about "Darwin and his Reviewers." The Origin of Species had been published less than a year earlier.)

These stories are obviously romances. They have happy endings. They appeared in print when Louisa was 27 years old, and she was paid $50 apiece for them. Another story of this sort is “Debby’s Début,” which appeared a few years later in the August 1863 issue (Google Books and The Atlantic archives). Deborah Wilder is an 18-year-old “countrified young thing” whose aunt wants “to take her to the beach and get her a rich husband.” She has a meet-cute with a man on the train who's trying to read her copy of Martin Chuzzlewit over her shoulder. At the beach the aunt’s advice is “make yourself interesting and don’t burn your nose,” and promptly introduces her to a man “from one of our first families, — very wealthy, — fine match.” Who do you think she ends up with?

It is also in Chapter 27 of Little Women that Jo sees a “pictorial sheet” with a story described as a “labyrinth of love, mystery, and murder” accompanied by a

melodramatic illustration of an Indian in full war costume, tumbling over a precipice with a wolf at his throat, while two infuriated young gentlemen, with unnaturally small feet and big eyes, were stabbing each other close by, and a disheveled female was flying away in the background, with her mouth wide open.

More importantly, the periodical is offering a hundred-dollar prize “for a sensational story.” Jo had previously only written “mild romances” but now attempts a different type of fiction “full of desperation and despair.” Six weeks later, she receives a check for $100.

Beginning in the 1860s, the word “sensation” was used to describe fiction that used elements of gothic and melodrama in stories of crime, revenge, madness, and sometimes the macabre and supernatural. The most accomplished practitioners were the English novelists Wilkie Collins (The Woman in White) and Mary Elizabeth Braddon (Lady Audley’s Secret), but a great deal of trashy (and now justifiably forgotten) sensation fiction was published as well

In real life, the periodical where Louisa May Alcott discovered this offer of a prize was Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper. The offer of $100 appears on page 114 of the November 15, 1962 issue. Louisa May Alcott turned 30 years old that month. On pages 209–210 in the December 27, 1862 issue a winner is announced, “and the first prize has been awarded to a lady of Massachusetts, for the story entitled, ‘PAULINE’S PASSION AND PUNISHMENT.’”

Amidst news reports of the Civil War and stunning illustrations of battles and generals, the first half of the story appeared (with illustrations) on pages 229–231 of the January 3, 1863 issue and the conclusion on pages 249–251 of the January 10, 1863 issue. The story involves a young woman who is jilted by her fiancé and decides to enact revenge by marrying a rich man and parading her success in front of him. However, things don’t go exactly as planned.

As you page through Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, you might also notice that a novel is being serialized with the title of Aurora Floyd. The author of was Mary Elizabeth Braddon, whose well-known novel, the aforementioned Lady Audley’s Secret had just been published in 1862 in a three-volume book form. Aurora Floyd is still in print today by Oxford World’s Classics.

Louisa May Alcott’s “Pauline’s Passion and Punishment” is one of four stories and novellas that were located in a literary sleuthing expedition begun in the 1940s by rare book dealers and longtime companions Leona Rostenberg and Madeleine Stern, and collected in the book Behind the Mask: The Unknown Thrillers of Louisa May Alcott (William Morrow & Co., 1975). It was followed the next year with Plots and Counterplots: More Unknown Thrillers of Louisa May Alcott, and in the decades since, several other collections have appeared.

In Chapter 34, Professor Bhaer will quite vehemently disapprove of Jo’s ventures into sensation literature. He calls them “bad trash” and says “they are not for children to see, nor young people to read. It is not well; and I haf no patience with those who make this harm.” As early as Chapter 27, Jo’s father also disapproves of these stories: “You can do better than this, Jo. Aim at the highest, and never mind the money.” Yet, there is something that justifies it all, and Jo

fell to work with a cheery spirit, bent on earning more of those delightful checks. She did earn several that year, and began to feel herself a power in the house; for by the magic of a pen, her “rubbish” turned into comforts for them all. “The Duke’s Daughter” paid the butcher’s bill, “A Phantom Hand” put down a new carpet, and “The Curse of the Coventrys” proved the blessing of the Marches in the way of groceries and gowns.

These are fictional titles, of course, but they are very much like the stories Miss Alcott wrote in the years preceding Little Women

There are sections of Part 2 of Little Women where Louisa May Alcott uses her skill at sensation fiction in recounting domestic horrors. Here’s Meg, now married to Laurie’s tutor John Brooke, eager to be (as the title of the English novel suggests) a “good wife”:

Fired with a housewifely wish to see her store-room stocked with home-made preserves, she undertook to put up her own currant jelly. John was requested to order home a dozen or so of little pots, and an extra quantity of sugar, for their own currants were ripe, and were to be attended to at once. As John firmly believed that “my wife” was equal to anything, and took a natural pride in her skill, he resolved that she should be gratified, and their own crop of fruit laid by in a most pleasing form for winter use. Home came four dozen delightful little pots, half a barrel of sugar, and a small boy to pick the currants with her. With her pretty hair tucked into a little cap, arms bared to the elbow, and a checked apron which had a coquettish look in spite of the bib, the young housewife fell to work, feeling no doubts about her success; for hadn’t she seen Hannah do it hundreds of times? The array of pots rather amazed her at first, but John was so fond of jelly, and the nice little jars would look so well on the top shelf, that Meg resolved to fill them all, and spent a long day picking, boiling, straining, and fussing over her jelly. She did her best; she asked advice of Mrs. Cornelius; she racked her brain to remember what Hannah did that she had left undone; she reboiled, resugared, and restrained, but that dreadful stuff wouldn’t “jell.” (ch. 28)

Anyone who’s even just peeked into a kitchen when canning was going on knows about the heat and the stifling humidity, and the hectic juggling of jars from counter to boiling water and back again, and the sweaty frustration when it’s not going well. In Meg’s case, this happens to be the day that John brings home a friend from work unannounced, and they witness a disaster. “In the kitchen reigned confusion and despair; one edition of jelly was trickled from pot to pot, another lay upon the floor, and a third was burning gaily on the stove.” Of course, John is clueless about what Meg has been going through. He hasn’t been there all day, and when Meg sobs, he laughs.

I feel like I’ve seen this scene before done for laughs, perhaps in a romantic comedy. But in Little Women it doesn’t seem at all funny to me. Here it seems more like a primeval or archetypal struggle of a wife trying to please her husband by doing the right thing, and the husband being typically oblivious about the sacrifices and frustrations. (“Now where’s my dinner?”)

In the years preceding Little Women, Miss Alcott also wrote a somewhat different genre of story that is not fictionalized at all in her novel. In late 1862, when she was 30 years old, she volunteered to be a nurse in a Union Army hospital in Georgetown. It only lasted about six weeks because she caught typhoid, one of several dangerous diseases (including measles) that plagued these hospitals.

Alcott wrote about these experiences in her first published book, the 102-page Hospital Sketches in 1863. Fictionalized somewhat — she assumed the ridiculous name of Tribulation Periwinkle — the author doesn't hide her politics. She describes herself as “a red-hot Abolitionist” and “a woman’s rights woman” and proclaims that “the blood of two generations of abolitionists waxed hot in my veins” and describes how during a trip to the Capital she “sat in Sumner’s chair and cudgelled an imaginary Brooks within an inch of his life.”

Soon after Miss Periwinkle begins working at the hospital she encounters men severely wounded but still inspiringly upbeat:

Another, with a gun-shot wound through the cheek, asked for a looking-glass, and when I brought one, regarded his swollen face with a dolorous expression, as he muttered —

“I vow to gosh, that’s too bad! I warn’t a bad looking chap before, and now I’m done for; won’t there be a thunderin’ scar? and what on earth will Josephine Skinner say?”

He looked up at me with his one eye so appealingly, that I controlled my risibles, and assured him that if Josephine was a girl of sense, she would admire the honorable scar, as a lasting proof that he had faced the enemy, for all women thought a wound the best decoration a brave soldier could wear. I hope Miss Skinner verified the good opinion I so rashly expressed of her, but I shall never know. (p. 36)

Miss Alcott knew that in writing this book, she was also creating uplifting propaganda for the Union cause. But she had somewhat higher objectives for herself:

I witnessed several operations; for the height of my ambition was to go to the front after a battle, and feeling that the sooner I inured myself to trying sights, the more useful I should be. Several of my mates shrunk from such things; for though the spirit was wholly willing, the flesh was inconveniently weak…. Dr. Z. suggested that I should witness a dissection; but I never accepted his invitations, thinking that my nerves belonged to the living, not to the dead, and I had better finish my education as a nurse before I began that of a surgeon. (pp. 96–97)

These experiences also provided some background for several stories with Civil War themes. One of them was “The Brothers,” published in the November 1863 issue of The Atlantic (Google Books and The Atlantic archives). The first person narrator is a nurse in a Union hospital asked by a doctor to care for “a Reb [who] has just been brought in crazy with typhoid.” Some nurses might decline out of loyalty to the Union but not she:

“Of course I will, out of perversity, if not common charity; for some of these people think that because I’m an abolitionist I am also a heathen, and I should rather like to show them, that, though I cannot quite love my enemies, I am willing to take care of them.”

She is offered the assistance of “a contraband,” which was a term given to self-emancipated slaves under the protection of the Union army. He’s a “fine mulatto fellow who was found burying his Rebel master after the fight…. His master’s son I dare say.” His face is badly mauled by a saber wound, but only on one side, emphasizing a kind of dual nature of the man. As the title “The Brother” suggests, the ex-slave is the half-brother of the Rebel soldier, and in revenge for sufferings he endured as a slave, is intent on killing him in the most painful way possible.

When the story was republished in an expanded edition of Hospital Sketches called Hospital Sketches and Camp and Fireside Stories in 1870, “The Brothers” was renamed “My Contraband.” This volume also contains several other Civil War stories originally published in more obscure periodicals. “Love and Loyalty” is about twin brothers who fight for the Union. “The Blue and the Gray” is about two wounded men, one Union, one Confederate, who shot each other on the battlefield and now lie side-by-side in the hospital. “A Hospital Christmas” describes a happy celebration, and in “An Hour,” an estranged son raised up north returns to his dying father’s plantation in the south, only to find that the 200 slaves held there are poised for rebellion. This story appeared in the Library of America volume American Antislavery Writings: Colonial Beginnings to Emancipation and is available in a PDF file.

In Little Women, Jo is a teenager during the Civil War, so there is nothing in the novel about her writings about the war and slavery. But I think these stories formed an important part of Louisa May Alcott's progress as a writer. In Little Women Jo writes some romances that don’t pay much, and sensation stories that pay considerably more, but Jo is also attempting a novel.

The novel that Jo is writing in Chapter 27 is the fictional version of Louisa May Alcott’s Moods, which became her second published book and first published novel. As in real life, Jo is asked to drastically cut the contents, and she does.

So, with Spartan firmness, the young authoress laid her firstborn on her table, and chopped it up as ruthlessly as any ogre. In the hope of pleasing every one, she took every one’s advice; and, like the old man and his donkey in the fable, suited nobody.

Also as with Moods, Jo’s first novel is not very successful.

The copies of Moods on Google Book Search and The Internet Archive have a copyright date of 1864 but curiously no publication date, yet judging from the title page, it’s obviously after 1870. A copy on Hathi Trust has a publication date of 1865, and is apparently a first edition. Alcott later revised Moods in 1882 and restored some of the material she had cut out. A scholarly edition published by Rutgers University Press in 1991 reproduces the first edition accompanied by an extremely illuminating introduction by literary historian Sarah Elbert, and includes chunks of the revised edition as well.

Moods is certainly a peculiar novel. A young woman named Sylvia, whose life is “a train of moods” (p. 116) goes on a partially metaphorical boat trip up a river with her brother and two of his friends, encountering glimpses of life, love, and death. The two friends fall in love with Sylvia, and she with one of them, but what we readers have learned in an introductory chapter that serves as a prologue, is that he is already engaged, and has been on a year-long probation before committing to the marriage.

In its meticulous dissection of personality traits, motivations, and shifting emotions, Moods sometimes seems to anticipate late Henry James, so it is quite curious that a review of Moods in the July 1865 issue of The North American Review was written by the 22-year-old Henry James himself. He doesn’t like it.

The relationship between the writings of the real-life Louisa and the fictional Josephine obviously intrigued me the most in Little Women, but I was also delighted by the little glimpses into simple unaffected domesticity, and observations of trivial but universal realism. I loved this description of the weather, for instance:

On Monday morning the weather was in that undecided state which is more exasperating than a steady pour. It drizzled a little, shone a little, blew a little, and didn’t make up its mind till it was too late for any one else to make up theirs. (ch. 26)

And who has never known a sofa like this one?

Now the old sofa was a regular patriarch of a sofa — long, broad, well-cushioned and low. A trifle shabby, as well it might be, for the girls had slept and sprawled on it as babies, fished over the back, rode on the arms, and had menageries under it as children, and rested tired heads, dreamed dreams, and listened to tender talk on it as young women. They all loved it, for it was a family refuge, and one corner had always been Jo’s favorite lounging place. Among the many pillows that adorned the venerable couch was one, hard, round, covered with prickly horse-hair, and furnished with a knobby button at each end; this repulsive pillow was her especial property, being used as a weapon of defence, a barricade, or a stern preventive of too much slumber. (ch. 32)

Little Women is ultimately about the tension between individualistic expression and domestic contentment. The March sisters are certainly encouraged to pursue their dreams. Besides Jo’s writing, Amy is an artist and Beth plays the piano. “I want my daughters to be beautiful, accomplished, and good; to be admired, loved, and respected,” Marmee says, but also

to have a happy youth, to be well and wisely married, and to lead useful, pleasant lives, with as little care and sorrow to try them as God sees fit to send. To be loved and chosen by a good man is the best and sweetest thing which can happen to a woman; and I sincerely hope my girls may know this beautiful experience. (ch. 9)

As a novel about children who learn through life’s experiences to gradually put away childish things and become adults, Little Women is clearly a Bildungsroman three times over. Let’s make that four times over, for Laurie, who suffers from rich-boy indolence for many years, has a lot of his own growing up to do.

What Little Women refuses to be is a Künstlerroman. We want accomplished artists to emerge from these girls’ lives, and they frustratingly do not. Instead, as the young people in Little Women mature, they begin treating their artistic pursuits as youthful conceits. Amy gives up her painting when she realizes she has no genius for it, but it’s not just the women that Miss Alcott is holding back from artistic success. Laurie similarly had dreams of being a great musician, and he gives up those pursuits to go into his grandfather’s business. Of course, this is extremely realistic. Only a few people can make a living as writers or artists or musicians. People find that they’re suited for different roles in life.

Jo is the most reluctant to grow up — she’s the Peter Pan of Little Women — but even she succumbs and gives up her writing (at least for now):

[T]he life I wanted then seems selfish, lonely and cold to me now. I haven’t given up the hope that I may write a good book yet, but I can wait, and I’m sure it will be all the better for such experiences and illustrations as these. (ch. 47)

Of course, we know that the real-life Jo was eventually able to write a novel because we’ve been reading it. But in Louisa May Alcott’s fictionalized version, this doesn’t happen until Jo’s Boys (published in 1886):

A book for girls being wanted by a certain publisher, she hastily scribbled a little story describing a few scenes and adventures in the lives of herself and sisters, though boys were more in her line, and with very slight hopes of success sent it out to seek its fortune. (ch. 3)

In Little Women proper, Jo’s progress from girl to woman is the most disturbing. Because she has the most potential, her fate seems like a cruel act of the author. For many decades, readers of Little Women yearned for Jo and Laurie to wed. Nowadays we’re just as inclined to wonder why Jo should get married at all. Louisa May Alcott never got married. Why should Jo?

Louisa May Alcott absolutely refused to marry Jo and Laurie, and when she finally allowed Jo to marry, she made sure that it was unconventional. Yet, there is plenty of evidence that Alcott had reservations about even an unconventional companionate marriage for Jo, and that Jo might have remained single. The foreshadowing is there: Early on, Marmee tells Meg and Jo that it is “better to be happy old maids than unhappy wives, or unmaidenly girls, running about to find husbands” (ch. 9). Jo tells Laurie “there should always be one old maid in a family” (ch. 24), and in a later chapter, when Jo is almost 25, she ruminates:

“An old maid — that’s what I’m to be. A literary spinster, with a pen for a spouse, a family of stories for children, and twenty years hence a morsel of fame, perhaps; when, like poor [poet and lexicographer Samuel] Johnson, I’m old, and can’t enjoy it — solitary, and can’t share it, independent, and don’t need it. Well, I needn’t be a sour saint nor a selfish sinner; and, I dare say, old maids are very comfortable when they get used to it; but —” and there Jo sighed, as if the prospect was not inviting. (ch. 43)

After more discussion of the conflicting pressures that women face in their lives, Louisa May Alcott addresses the reader directly:

Gentlemen, which means boys, be courteous to the old maids, no matter how poor and plain and prim, for the only chivalry worth having is that which is the readiest to pay deference to the old, protect the feeble, and serve womankind, regardless of rank, age, or color. Just recollect the good aunts who have not only lectured and fussed, but nursed and petted, too often without thanks — the scrapes they have helped you out of, the “tips” they have given you from their small store, the stitches the patient old fingers have set for you, the steps the willing old feet have taken, and gratefully pay the dear old ladies the little attentions that women love to receive as long as they live. (ch. 43)

The readership of Little Women has likely always been mostly young and mostly female, yet it is interesting that in one of the few cases when the author addresses the reader directly — and later apologizes that she has put her readers to sleep for doing so — she talks to boys.

There comes a time in a Künstlerroman when the hero synthesizes all her past writing experience — in this case, the domestic theatricals, the newspaper occassonals, the romances in periodicals, the sensation stories, and a novel of deep psychological insight — and creates something profound and great. But at that point in Little Women, Jo gives it all up. One of the more interesting scholarly essays in the Norton Critical Edition of Little Women asserts that Miss Alcott applied her skills at sensation fiction by killing off her heroine and performing a switcheroo: It was Jo rather than Beth who dies of the nondescript wasting disease, and Beth takes Jo’s place in the novel:

Like Cassy, the horribly abused slave woman of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, and like Sethe, the equally besieged black woman of Toni Morrison’s Beloved, Alcott chooses to murder her dearest child rather than force that child to live in a world hostile to her. Alcott’s murder of Jo, then, is the secret violence at the center of Little Women. Alcott’s response to her fiction seems characteristic of the woman or the woman writer beset by irreconcilable conflicts and demands: Jo finds herself among the good who must die young. In order that she not be corrupted by the adult world of heterosexuality, Joe must be killed while at her zenith of eager and fiery independence. (“Dismembering the Text: The Horror of Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women” by Angela M. Estes and Kathleen Margaret Lant)

Another scholar sees the Civil War as a metaphor for Jo's (and Louisa's) internal conflicts. Jo is an angry woman, and so was Louisa. What the sensation stories "make clear is the amount of rage and intelligence Alcott had to supress in order to attain her 'true style' and write Little Women." When Jo agrees to marry Professor Bhaer,

It is difficult not to see it as capitulation and difficult not to respond to it with regret. Our attitude, moreover, is not the result of feminist values imposed on Alcott's work but the result of ambivalence without the work on the subject of what it means to be a little women. Certainly, this ambivalence is itself part of the message of Little Women. It accurately reflects the position of the woman writer in nineteenth-century America, confronted on all sides by forces pressuring her to compromise her vision. (Judith Fetterley, "Little Women: Alcott's Civil War", Feminist Studies, Vol. 5, No. 2 (Summer, 1979), pp. 369–383)

In Jo's Boys, Louisa May Alcott demonstrated how easy it was to have Jo write a novel much like Little Women. Could she have done that in Little Women itself? It's not hard to imagine. In the last paragraphs of the final chapter she could have described a conversation between Jo and a publisher who suggests she write a novel for girls, and Alcott could have concluded (presaging Gertrude Stein) “And she has, and this is it.”

Or would that have been much too self-referential in 1869. Would it have made the first readers’ heads explode?

Interestingly, there have been people who have fixed this flaw in Little Women. These are the many writers and directors who have adapted the novel for the big and small screen over and over and over again. Anne Boyd Rioux devotes a whole chapter to the various stage, screen, and radio adaptations. The first two silent films of Little Women are apparently lost, but many of the others are available for convenient streaming.

The 1933 film directed by George Cukor is fairly faithful to the novel. I recognized chunks of dialogue. But all the actresses are too old. Most notoriously, the preteen Amy is played by a pregnant Joan Bennett. The biggest draw in the movie is seeing Katherine Hepburn as Jo, emphasizing the tomboy more than the writer. It’s certainly a fun performance, but I never quite believed it. It seems too much like a twenty-something women imitating a teenage tomboy. I was reminded of the jail scene in Bringing Up Baby where Hepburn impersonates a hard-boiled gangster. In that scene, the ham is intentional, but it’s not quite pleasant as Jo.

Setting a precedent that other adaptations will follow, the movie ends with Jo’s book being published, although it seems to happen without her permission, without her review of proofs, and she cares less about the book than about Professor Bhaer.

The 1949 color film directed by Mervyn LeRoy reproduces the book’s opening dialogue, but many of the scenes are lifted from the 1933 version. For example, Professor Bhaer — who is Italian rather than German in this version and played by Rossano (“Some Enchanted Evening”) Brazzi — nevertheless makes his first appearance in a bear rug in both movies, which is not in the book. Three screenwriters are credited in this version; one wonders what they did.

I generally enjoyed the casting of this version more than the 1933 film. I thought the appropriately unglamorous June Allyson to be a fine rowdy Jo, and the other women fit well also: Janet Leigh (a decade before Psycho) is Meg, and Mary Astor (just 8 years after taking the fall in The Maltese Falcon) is Marmee.

The most radical decision made by the filmmakers was to swap the ages of Amy and Beth. This switch is initially quite disorienting, but it’s entirely justified by the casting, for it allows Amy to be played a 16-year-old Elizabeth Taylor with strawberry-blonde hair and hilarious streaks of vanity. The tragic Beth is taken on by the 11-year-old freckled, sullen, and delicate Margaret O’Brien. The scene when she comes back sick from the Hummels, and you see her in a long shot leaning awkwardly against the inside of the front door, is devastating. She looks quite vulnerable and frighteningly ill. Dramatically and psychologically, it makes more sense for Beth to be the youngest sister, so I ultimately decided that switching them was a brilliant move.

As with the 1933 film, this one ends with Jo’s book being published. The title is My Beth, which is the title of a poem in the novel.

This 1978 two-episode television miniseries might at first seem ridiculous, combining as it does stars of Family Ties, The Partridge Family, The Brady Bunch, Marcus Welby, M.D., and Star Trek, but it’s a credible effort, and the extra hour of screen time gives the characters and situations more room to develop.

Susan Dey — at the time in that awkward stage of life between The Partridge Family and L.A. Law — is a bold and forward Jo, not quite a classic tomboy but believable as an earnest writer. She and Meredith Baxter Birney as Meg really look like they could be sisters. Jo is given a voiceover — emphasizing that she’s really the most important character and could have narrated the whole of Part 1 of the novel — and this version includes actual mentions of the war, as well as Lincoln and Grant.

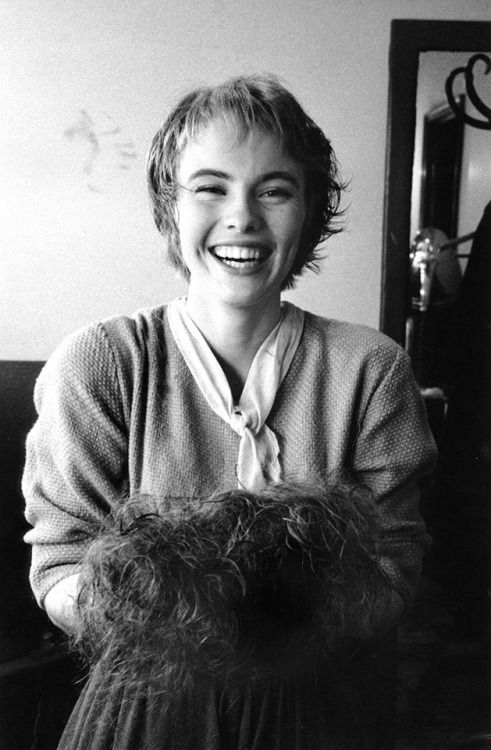

I was delighted immensely by the worst-sounding piano ever in the March house before the arrival of the new one, but when Jo gets her hair cut off, there’s something wrong with Susan Dey’s wig or whatever they put on top of her head. It looks like a helmet. Is no actress willing to match the courage of Jean Seberg 60 years ago when she got hired to play Joan of Arc?

Look how happy she is holding all that useless hair that’s just been cropped from her head!

The other jarring aspect of this version is the casting of Professor Bhaer, who has an atrocious German accent and even worse German! But for a true “when worlds collide” TV experience, there is nothing quite like seeing a love scene between Laurie Partridge and Captain James T. Kirk.

It’s too bad John Hughes or Joel Schumacher didn’t direct a 1980s Brat Pack version of Little Women. I see Molly Ringwald as Meg, Ally Sheedy as Beth, Demi Moore as Amy, Mare Winningham as Marmee, and of course, Mary Stuart Masterson with her Some Kind of Wonderful haircut as Jo. James Spader is Laurie, Andrew McCarthy is Brooke, and Judd Nelson doesn’t quite manage his accent for Professor Bhear. Damn, I’d see that movie.

Until recently, the 1994 film by Gillian Armstrong was the definitive version for the younger generation. It retains many of the situations and plot of the book but most of the dialogue is completely rewritten. As in the 1978 TV version, Jo has an occasional voiceover. Susan Sarandon is a strong feminist Marmee, Kirsten Dunst is great as young Amy (Samantha Mathis less so as older Amy), but Claire Danes is wasted as Beth, and Winona Ryder seems too respectful of the material to really explore Jo’s character sufficiently. At the end we hear lines from the novel as Jo is writing it.

The recent Little Women sesquicentennial has inspired a small surge of additional adaptations.

A 2017 BBC miniseries (aired in the US on PBS in 2018) consists of three one-hour episodes. It was adapted by Heidi Thomas and directed by Vanessa Caswill, and uses a mix of English and American actors, with Emily Watson as Marmee, Angela Lansbury as Aunt March, Maya Hawke (the daughter of Ethan Hawke and Uma Thurman who delighted us Stranger Things fans with her portrayal of Robin at the mall ice-cream parlor) as Jo, Kathryn Newton (who played the older Joanie Clark in Halt and Catch Fire) as a great Amy, and Michael Gambon (Dumbledore II) as Grandfather Lawrence.

This version tones down Jo the tomboy and emphasizes the writer. There are frequent closeups of faces and a meticulous attention to domestic activities, clothing, and medical implements that give it a good period feel. It has the aura of extensive research, but marred by some jarring music. The scenes of Jo writing in her garret with her writing cap, inkwell, pen, and candles look great, and I loved the sensuous closeups of shiny wet black streams of ink on paper.

This version includes the publication of Jo’s first failed novel, and there’s a humorous line about Jo getting paid $20 for sensation stories, but only $10 for stories about sisterly love. Towards the end, however, Jo says “I’ve got some writing to do.” Don’t give up!

The 2018 movie directed by Clare Niederpruem moves the action to the present day. The sisters are homeschooled, they record their attic theatricals with camcorders, they communicate with their army doctor father with Skype, Laurie plays the guitar and Beth plays electronic keyboard, yet these modern girls still have a Pickwick Club and Jo writes by longhand.

A much greater offense is chopping up the narrative to bounce back and forth between Parts 1 and 2 of the novel. Professor Bhaer (an accentless hunk who teaches at Columbia) appears very early in the movie, which makes his eventual hookup with Jo seem inevitable when he should really be the most unexpected plot twist of the story. Relative unknowns are cast as younger and older versions of the sisters, but Lea Thompson is Marmee.

Towards the end, Jo begins to write the book she was meant to write, and without which the movie would be impossible. In less than a minute of screen time later, she deposits the manuscript in a manilla envelope, and Professor Bhaer finally approves. (And that's what's really important, right?)

The major flaw of Greta Gerwig’s new film is the same as the 2018 version: it chops up the narrative to bounce back and forth between Parts 1 and 2. The movie begins with Jo in New York (with an early appearance by Professor Bhaer) and Amy is studying art in Paris. This scrambling adds nothing except confusion. Beth is on the way to death before she gets scarlet fever, and we learn that Jo has rejected Laurie before she actually does so. Even after reading the novel and seeing six other adaptations, I was frequently disoriented, and not pleasantly. The fragmentation of the narrative arc did not contribute to my overall aesthetic experience.

This is a shame because otherwise the film is impeccable. It has a good period feel, and realistically dark interiors. I love the casting: Saoirse Ronan as Jo, Emma Watson as Meg, Florence Pugh (so good in Lady Macbeth) as Amy, Laura Dern as a better Mom than in Big Little Lies, and in the role that her entire career has been leading up to, Meryl Streep as Aunt March. As an extra bonus, when daddy March shows up, it's Bob Odenkirk!

Other than the bouncing back and forth, Gerwig is fairly faithful to the book. Even the opening dialogue of the book is reproduced, but with the sisters talking on top of each other. I don’t think I’ve heard so much tumbling overlapping dialogue since the heyday of Robert Altman. It's wonderful!

And yes, as has become fairly standard now in Little Women adaptations, Greta Gerwig includes a scene of Jo writing the book. We see the opening sentence (“Christmas won’t be Christmas without any presents”…), and many more pages, as candles are lit and Jo burns. At one point, Jo lays all the handwritten pages out on the floor, which Gerwig as a writer knows is a great way to get a flow and balance of the narration.

This is followed by some of the sexiest book-printing footage ever. Type is set up, pages are rolled over the press, signatures are sewn together, then cut and pasted between hard covers. A metal plate on the cover reads Little Women. And then Jo holds her new book to her chest like a newborn babe.

This is the miracle of writing. The labor is often long and excruciating, but at the end a child is produced that will not die by scarlet fever or the guns of war or even old age.

This is a child that will live forever.