The Lesser-Read George Eliot

November 22, 2019

Sayreville, N.J.

Today is the 200th anniversary of the birth of George Eliot, and I thought I’d celebrate by reading the more obscure books of hers that I’ve been neglecting over the years. In other words: I’ve read the best, now read the rest.

I suspect that my list of neglected books might be the same as those of some other fans of the author. For me, there are five such books: two translations of German theology, an historical novel set in 1490s Florence, an epic poem set in 1490s Spain, and something that is modernly fictionish but not quite a novel.

Most of the works of George Eliot are conveniently available in familiar Penguin or Oxford World’s Classic editions that combine authoritative texts, enlightening introductions, and notes that clarify obscure or outdated references. With one exception, the books I’ve chosen for this survey are not readily available in modern editions.

The two translations might at first seem inconsequential, but I think they’re necessary. These are George Eliot’s two earliest books, published before she established her famous pseudonym when she was still Mary Ann Evans and later, Marian Evans. She spent a lot of time on them, so these books were important to her. In influencing her philosophical and religious thinking, they are crucial aspects of her education. A recent biography, The Transferred Life of George Eliot by Philip Davis (Oxford University Press, 2017) devotes a whole chapter to her translations.

The two translations are both from German theological texts with innocent titles that mask explosive contents. After the English versions became available, these books were also important for everyone who read them or who were touched by their contents, because they contributed to what historian Owen Chadwick famously called in the title of his 1975 book: The Secularization of the European Mind in the 19th Century.

The Life of Jesus, Critically Examined by David Strauss (1846)

In early 1844, the 24-year-old Mary Ann Evans began translating a 1500-page work of radical theology by German theologian David Friedrich Strauss entitled Das Leben Jesu, kritisch bearbeitet, a translation job complicated by a text peppered with Bible quotations in Hebrew and Greek, and Latin quotations from the Vulgate.

How did it happen that someone so young could take on such a project?

Let’s begin this story with the 1836 marriage between Charles Bray (b. 1811), the owner of a prosperous ribbon-weaving manufactory in Coventry, and Caroline Hennell (b. 1814). Although Cara (as she was known) was from a Unitarian family, and herself of less orthodox religious beliefs, she hadn’t quite realized the extent of her new husband’s skepticism concerning Christianity until their honeymoon in Wales.

Somewhat disturbed by her husband’s views, Cara asked one of the smartest people she knew to evaluate them. This was her older brother Charles Hennell (b. 1809), who then spent two years studying the New Testament and writing a book An Inquiry Concerning the Origin of Christianity, published in 1838. Hennell concluded that the Gospels were a mix of reportage and myth. The story of Jesus and his moral teachings could be separated from the historically dubious accretions of miracles, including the virgin birth and resurrection.

In writing his Inquiry, Charles Hennell didn’t know that German theologians had for some time been analyzing the texts of the Bible similarly in what became known as the “higher criticism.” This term distinguished this work from the “lower criticism” of manuscript studies. Once the lower criticism establishes the historical texts of the Bible, the higher criticism builds on that to extract the meaning of the texts, and (as this work developed) separate the contents into truth and fable.

One of the results of this research among the German theologians was the controversial 1835 book by David Friedrich Strauss entitled Das Leben Jesu, kritisch bearbeitet, which was even more extreme than Hennell’s book, concluding that very little in the Gospels could be trusted as fact.

Strauss was not so much older than the other personages here. He was born in 1808, and in 1832 began lecturing at the theological college at Türbingen, which was a hotbed of advanced theological pursuits. He soon began writing his life of Jesus, which appeared in two volumes in 1835. As Albert Schweitzer wrote in The Quest of the Historical Jesus (in the first of three chapters on Strauss), the book “rendered him famous in a moment — and utterly destroyed his prospects” (p. 71). Strauss could no longer be employed by any German university.

Strauss was introduced to Hennell’s Inquiry by English physician Robert Herbert Brabant (b. 1781) in 1839. Strauss was apparently impressed enough to have Hennell’s book translated into German as Untersuchung Über Den Ursprung Des Christenthums around 1840. Meanwhile, Strauss had been revising his own work, creating a 3rd edition in 1838 that toned down some of his conclusions, and a 4th edition in 1840 that restored much of the original text.

Charles Hennell met Dr. Brabant in 1839, and also his daughter Elizabeth Rebecca Brabant (b. 1811), known as Rufa for her red hair. Charles Hennell and Rufa quickly became engaged but were not married until 1843. These interlocking families became known as the “Rosehill Circle,” after the home of Charles and Cara Bray in Coventry.

In 1840, Mary Ann Evans and her father moved to Coventry. In her younger years, she went through a period of rather severe evangelical Christianity, but she had been veering away from it, partially as a result of much reading in philosophy, religion, and science. In August 1841, a second edition of Charles Hennell’s An Inquiry Concerning the Origin of Christianity was published. Mary Ann Evans knew of the Hennells and the Brays through one of her neighbors, and she was also quite impressed with Hennell’s book.

Soon after reading Hennell’s Inquiry, Mary Ann declared her famous “holy war” early in 1842 and announced she would no longer go to church. In a letter to her father she said the scriptures were “histories consisting of mingled truth and fiction, and while I admire and cherish much of what I believe to have been the moral teaching of Jesus himself, I consider the doctrines built upon the facts of his life ... to be most dishonourable to God and most pernicious in its influence on individual and social happiness.” (The George Eliot Letters, ed. Gordon S. Haight, Vol 1, Yale University Press, 1954, p. 128) Attempts to dissuade her came to naught. One Baptist minister who tried came away from the encounter chastened: “That young lady must have had the devil at her elbow to suggest her doubts, for there was not a book that I recommended to her in support of Christian evidences that she had not read.” (Kathryn Hughes, George Eliot: The Last Victorian, Farrar Straus Giroux, 1998, p. 53)

British attorney, philosophical radical, and reformist politician Joseph Parkes (b. 1796) proposed funding an English translation of Strauss’s Das Leben Jesu. Any weakening of conservative Anglican orthodoxy was believed to be good for progressive social and political reform. The translation job bounced around the Rosehill Circle: Charles Hennell was first approached. He asked his sister Sara (b. 1812), but she didn’t want it. It then went to Rufa Brabant, who translated about 250 pages (about 15%) of the German text. After Rufa married Charles in 1843, she found that the translation couldn’t compete with her new domestic role.

By this time, Mary Ann Evans had become part of the Rosehill Circle, and enjoyed socializing and exchanging ideas with this extended family of freethinkers. They in turn recognized her intelligence, and she took over from Rufa’s translation to complete the job.

Unbeknownst to them all, another translation of Strauss’s Das Leben Jesu was in progress, but for an entirely different audience. During this era in British history, a working-class audience existed for publications that combined political radicalism and religious atheism. (Interestingly, penny periodicals targeting this audience also explored pre-Darwinian theories of transmutation of species, or what we would today call evolution. This phenomenon is explored in Adrian Desmond’s fascinating paper “Artisan Resistance and Evolution in Britain, 1819–1848”, Osiris, Vol. 3, 1987, pp. 77–110.) According to Friedrich Engels’ The Condition of the Working Class in England, this earlier translation of Strauss was read by workers in Manchester.

The inexpensive working-class edition of Strauss’s Life of Jesus was published by Henry Hetherington, who was a perennial target for Britain’s blasphemy laws. (See Chapter 2 of Joss Marsh’s Word Crimes: Blasphemy, Culture, and Literature in Nineteenth-Century England, University of Chicago Press, 1998. See also “Strauss’s English Propagandists and the Politics of Unitarianism, 1841–1845” by Valerie A. Dodd, Church History, Vol. 50, No. 4, Dec. 1981, pp. 415–435, for a discussion of Strauss’s English translators.)

The British Library has this working-class translation of Strauss in four volumes: Vol. I (1842), Vol. II (1842), Vol. III (1843), Vol. IV (1844). The translator is anonymous and remains unknown.

Mary Ann Evans found the job of translating Strauss to be slow and brutal “soul-stupefying labour,” (George Eliot Letters, Vol. I, p. 185), and not only because of the book’s length. Strauss’s scholarly savagery offered nothing to compensate for his relentless analysis and destruction of every element of the gospels that had nurtured Mary Ann’s early life and, indeed, the past eighteen centuries of Western Civilization. She kept an engraving of Christ and an ivory image of the crucifixion at her desk while she worked. Cara Bray wrote to her sister Sara Hennell in 1846: “She said she was Strauss-sick — it made her ill dissecting the beautiful story of the crucifixion, and only the sight of her Christ-image and picture made her endure it.” (George Eliot Letters, Vol. I, p. 206)

Three months later, on the eve of publication, Mary Ann seemed to have somewhat recovered when she wrote in a letter to Sara “I do really like reading our Strauss — he is so klar und ideenvoll but I do not know one person who is likely to read the book through, do you?” (George Eliot Letters, Vol. 1, p. 218)

Mary Ann Evans’ translation was published in three volumes in 1846. Google Books has three complete copies from three different sources, but all associated with Harvard in some way:

- Harvard College Library: Volume 1, Volume 2, Volume 3

- Andover Theological Seminary: Volume 1, Volume 2, Volume 3

- Radcliffe Institute: Volume 1, Volume 2, Volume 3

Mary Ann’s name did not appear on the cover or within the book, and after two years of work, she was paid only £20 for her work. But it did bring her to the attention of publisher John Chapman, who was to give her a job of editing the Westminster Review (in whose pages some of her first work appeared), and he later published many of her novels. They may also have had an affair.

Although the cheap edition of The Life of Jesus was threatened with blasphemy prosecution, that was because it was targeted towards the potentially revolutionary working class. John Chapman probably would have welcomed a blasphemy prosecution just for the publicity, but he was too respectable a publisher for that, and he sold his books to a more complacent audience.

In 1892, a second edition of Evans translation of The Life of Jesus incorporated some corrections and the pages were reset for a higher word density. Consequently the page count was reduced by nearly a half, and the whole thing was published in one volume. George Eliot is credited as translator and a 22-page introduction by German theologian Otto Pfleiderer is included. This edition is available in printed form without the Pfleiderer introduction but with a new 50-page introduction by Peter C. Hodgson. It was published by Fortress Press in 1972 and Sigler Press in 1994.

Obviously there are many options for reading this book. Few of us can know what it’s like to spend two years translating a book as long and as difficult as Strauss’s Life of Jesus, but I thought I’d try to come as close as possible by reading the whole thing. (Due to disgraceful gaps in my education, I had to glide over the Hebrew, Greek, and Latin, although I did learn that κ.τ.λ. is an abbreviation for και τα λοιπά, which means “and so on,” or in Latin, et cetera.) The page references below refer to the 1846 edition, although the division of the book into three parts, 20 chapters, and 152 sections should make it easy to find these quotations in the 1892 edition.

Reading The Life of Jesus is an experience like no other, but the title is not quite accurate. This is not a life of Jesus. Instead, it is a meticulously detailed demonstration that a trustworthy account of this life is not possible given the nature of the source material. Strauss ruthlessly and mercilessly dissects the four Gospels attempting to extract accurate narratives, only to find internal inconsistencies, contradictions, and implausible events. The accounts of miracles in particular leave him skeptical, for they seem unworthy of God as well as contrary to the laws of nature.

Passages in the New Testament that seem short, inconsequential, and uncontroversial are spread open like a frog on a Middle Schooler’s science-lab desk, and relentlessly poked and prodded. Strauss spends six pages on Mary’s visit to her sister Elizabeth (Part 1, Chapter III, §31), for example, and his scrupulousness never flags. Towards the end he has enough energy to spend seven pages on the spear wound in Jesus’s side (Part 3, Chapter IV, §134).

Throughout Life of Jesus, Strauss carries on a type of dialog with earlier (mostly German) analysts of the New Testament. Frequently appearing in the texts are the now less-famous names of Heinrich Paulus (who had written a life of Jesus in 1828), Hermann Olshausen (the author of several books on the New Testament), and Friedrich Schleiermacher. Earlier interpreters of the New Testament tended to pursue one of two different explanations of the miracles: The supernaturalists (or as it’s spelled in this translation, supranaturlists) assumed that tales of miracles were accurate, while the naturalists argued that the accounts resulted from faulty or misunderstood eyewitness testimony of natural events.

Strauss rejects these interpretations. He instead treats the gospels as myths that have been fashioned to reinforce the legitimacy of Old Testament prophecy.

For example, Part I, Chapter IV is devoted to the birth of Jesus. Sections explore the census, the flight into Egypt, the massacre of the Innocents, the manger (or possibly a cave) in Bethlehem, and the Magi. Strauss concludes:

Thus the evangelical statement that Jesus was born at Bethlehem is destitute of all valid historical evidence; nay, it is contravened by positive historical facts. We have seen reason to conclude that the parents of Jesus lived at Nazareth, not only after the birth of Jesus, but also, as we have no counter evidence, prior to that event, and that, no credible testimony to the contrary existing, Jesus was probably not born at any other place than the home of his parents. With this twofold conclusion, the supposition that Jesus was born at Bethlehem is irreconcilable: it can therefore cost us no further effort to decide that Jesus was born, not in Bethlehem, but, as we have no trustworthy indications that point elsewhere, in all probably at Nazareth. (Part 1, Chapter IV, §39; Vol. I, pp. 267–8)

Why then would the evangelists write that Jesus was born in Bethlehem? Because Micah 5:1–2 says that a “ruler in Israel” will come from Bethlehem, and it was important to early Christians that the Messiah fulfill Old Testament prophecy.

That summary paragraph is characteristic of Strauss’s verbose and laborious style. It is very hard to find pithy quotes. Yet, I did not find the book boring. Strauss devotes Part 2, Chapter IX to the miracles performed by Jesus — over 200 pages in the 1846 edition — which I found quite engrossing. I had never considered the improbability of a legion of demons leaving a man and entering a herd of swine, which then drown themselves, but Strauss makes it fascinating (Part 2, Chapter IX, §93; Vol II, p. 256ff). Nor had I ever considered the implications of the three synoptic Gospels apparently ignoring the resurrection of Lazarus (Part 2, Chapter IX, §100; Vol. II, p. 369ff). Lazarus is definitely the most impressive example of resuscitation of the dead. Why then did Matthew, Mark, and Luke not know about it?

Today's liberal Christians are much less concermed with the miracles of Jesus but remained attuned to his moral teachings. Even some agnostics and atheists find value in passages such as the Sermon on the Mount. I myself was very curious about Strauss's analysis of this text, and an explanation of the differences between the versions in Matthew and Luke. Here is Strauss's discussion of the Beatitudes (Part II, Chapter VI, §76; Vol II, pp. 100–101):

In both editions, the sermon on the mount is opened by a series of beatitudes; in Luke, however, not only are several wanting which we find in Matthew, but most of those common to both are in the former taken in another sense than in the latter. The poor, πτωχοὶ, are not specified as in Matthew by the addition, in spirit, τῷ πνεύματι; they are therefore not those who have a deep consciousness of inward poverty and misery, but the literally poor; neither is the hunger of the πεινῶντες (hungering) referred to τὴν δικαιοσύνην (righteousness); it is therefore not spiritual hunger, but bodily; moreover, the adverb νῦν, now, definitely marks out those who hunger and those who weep, the πεινῶντες and κλαίοντες. Thus in Luke the antithesis is not, as in Matthew, between the present sorrows of pious souls, whose pure desires are yet unsatisfied, and their satisfaction about to come; but between present suffering and future well-being in general. This mode of contrasting the αίὼν οὖτος and the αίὼν μέλλων, the present age and the future, is elsewhere observable in Luke, especially in the parable of the rich man; and without here inquiring which of the two representations is probably the original, I shall merely remark, that this of Luke is conceived entirely in the spirit of the Ebionites, — a spirit which has of late been supposed discernible in Matthew. It is a capital principle with the Ebionites, as they are depicted in the Clementine Homilies, that he who has his portion in the present age, will be destitute in the age to come; while he who renounces earthly possessions, thereby accumulates heavenly treasures. The last beatitude relates to those who are persecuted for the sake of Jesus. Luke in the parallel passage has, for the Son of man’s sake; hence the words for my sake in Matthew, must be understood to refer to Jesus solely in his character of Messiah.

The beatitudes are followed in Luke by as many woes οὐαὶ, which are wanting in Matthew. In these the opposition established by the Ebionites between this world and the other, is yet more strongly marked; for woe is denounced on the rich, the full, and the joyous, simply as such, and they are threatened with the evils corresponding to their present advantages, under the new order of things to be introduced by the Messiah; a view that reminds us of the Epistle of James, v. 1 ff. The last woe is somewhat stiffly formed after the model of the last beatitude, for it is evidently for the sake of contrast to the true prophets, so much calumniated, that the false prophets are said, without any historical foundation, to have spoken well of by all men. We may therefore conjecture, with Schleiermacher, that we are indebted for these maledictions to the inventive fertility of the third gospel. He added this supplement to the beatitudes, less because, as Schleiermacher supposes, he perceived a chasm, which he knew not how to fill, then because he judged it consistent with the character of the Messiah, that, like Moses of old, he should couple curses with blessings. The sermon on the mount is regarded as the counterpart of the law, delivered on Mount Sinai; but the introduction, especially in Luke, reminds us more of a passages in Deuteronomy, in which Moses commands that on the entrance of the Israelitish people into the promised land, one half of them shall take their stand on Mount Gerizim, and pronounce a manifold blessing on the observers of the law, the other half on Mount Ebal, when they were to fulminate as manifold a curse on its transgressors. We read in Josh. viii. 33ff. that this injunction was fulfilled.

One certainly sympathizes with Mary Ann, searching desperately for a few words that acknowledge the stately beauty and depth of feeling in the Beatitudes, and finding no oxygen in Strauss whatever. We are reminded instead of the Reverand Edward Casaubon's ridiculous proposal of marriage to Dorothea in Middlemarch 25 years later. Casaubon may have been modeled on David Strauss but his Key to All Mythologies is the reverse of Strauss's book. Casaubon intended to show "that all the mythical systems or erratic fragments in the world were corruptions of a tradition originally revealed" (ch. 3) — that is, that all pagan myths derive from Biblical truths. It is Casaubon's cousin Will who is more familiar with German Higher Criticism and sees the flaws in Casaubon's approach.

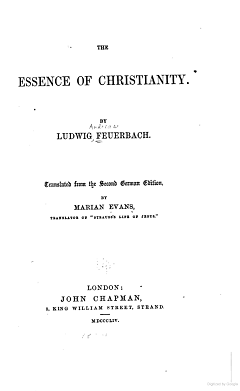

The Essence of Christianity by Ludwig Feuerbach (1854)

In 1851, Mary Ann Evans moved to London and around this time became known as Marian Evans. This is when she started working for John Chapman in editing the Westminster Review and writing anonymous reviews for it. Her first for this periodical was a review of The Progress of the Intellect, as Exemplified in the Religious Development of the Greeks and Hebrews by Robert William Mackay (Westminster Review, Vol. LIV, Jan. 1851, pp. 353–368). In George Eliot: The Last Victorian, Kathryn Hughes writes:

To read the ten issues for which Marian Evans was responsible [January 1852 through April 1854] is to be presented with a snapshot of the best progressive thought at mid-century. The way forward in education, industry and penal reform is mapped out. Science is well covered, especially those pathways which lead inexorably towards Darwin — geology, botany, biology. Herbert Spencer introduces his theory of evolution over four issues. (p. 111)

Marian also had an opportunity to translate another work of German theology. Ludwig Andreas von Feuerbach (1804–1872) began his studies as an aspiring theologian, but partially under the influence of Hegel and his own intellectual development, he shifted his focus to philosophy and anthropology. His book Das Wesen des Christentums (1841; second edition, 1848) adopted an anthropological analysis of Christianity, conceiving religion to be a manifestation of mankind’s human nature. It was quite popular among German readers, as well as influential in German philosophy throughout the 19th century, including the thought of Marx and Richard Wagner. Friedrich Engels wrote a book about Feuerbach.

The Feuerbach translation went much smoother and faster than the Strauss. The book was shorter, the German was easier, and the prose considerably livelier. Most importantly, the content was more amenable to Evans’ own ideas, and more similar to Charles Hennell’s book. The 340-page result was published in July 1854 by John Chapman, with a title page that identifies the translator for both this book and the earlier one:

THE

ESSENCE OF CHRISTIANITY.

BY

LUDWIG FEUERBACH.

Translated from the Second German Edition,

BY

MARIAN EVANS,

TRANSLATOR OF “STRAUSS’S LIFE OF JESUS.”

That recognition must have been gratifying, but this is the only time that the name of Marian Evans would appear on one of her books.

Google Books has a copy of the original edition. A second edition was published in 1881, and although it claims to be an “exact reprint,” it is not, although the page numbers correspond closely. This second edition has been republished in facsimile in more recent years. I own a Harper Torchbook edition published in 1957 with a short Foreward by H. Richard Niebuhr (younger brother of Reinhold), a critical Introductory Essay by Karl Barth, and backcover blurbs by Martin Buber and Sidney Hook. This is the edition I’ve seen referenced in some academic articles, although apparently without the knowledge that the page numbers differ from the first edition. I also have a paperback published by Prometheus Books in 1989 as part of their Great Books in Philosophy series. Although this is a facsimile reproduction of the 1881 edition, the title page is omitted, so the book has no indication when the translation was first published.

Page numbers below refer to the first edition.

In a sense, Feuerbach was picking up the pieces after the devastating blows of the 1830s. It wasn’t only David Strauss chipping away at Bible stories. Researches in geology had revealed a world much older than the Biblical chronology suggested, and even the great Deluge had been abandoned by mainstream geologists. Natural philosophers still assumed that the myriad of living species on the earth implied the work of a Creator, but some people even believed that species might transmute into other species in accordance with natural law.

To Feuerbach, religion — and in particularly, Christianity — remains important because it reveals to us what we consider the highest of human ideals. Our inner human feelings of love, justice, charity have been projected outward to form our concept of God. This very human God is a major component of Christianity, for God is manifested in human form through Jesus. In Feuerbach’s view, an abstract God stripped of human attributes is no God at all. Although a God with human attributes reflects our ideals, the trappings of religion that surround God can also harden into dogma, which become contrary to these ideals.

After an introductory chapter, Feuerbach has a large section on “The True or Anthropological Essence of Religion.” This he considers to cover the “positive” aspects of his argument, that “Theology is Anthropology, that there is no distinction between the predicates [i.e., attributes] of the divine and human nature, and consequently, no distinction between the divine and human subject” (page ix). The second part is “The False or Theological Essence of Religion,” mostly given to showing contradictions in the existence of God, contradictions in revelation, contradictions in the Trinity (which by this point is like shooting fish in a barrel), and contradictions in the sacraments.

Judging from George Eliot’s translation, Feuerbach’s prose is lively, pithy, and eminently quotable. This is not to say that it’s easy to comprehend. Feuerbach tends to overload certain words such as religion, theology, and even God with multiple meanings depending on the context. The style at times seems almost improvisatory, a form of dialectical jazz, and the effect is dizzying.

A few extended quotes will give the flavor of this unusual but extraordinary book. These are from the chapter “God as a Moral Being, or Law”:

Of all the attributes which the understanding assigns to God, that which in religion, and especially in the Christian religion, has the pre-eminence, is moral perfection. But God as a morally perfect being is nothing else than the realized idea, the fulfilled law of morality, the moral nature of man posited as the absolute being; man’s own nature, for the moral God requires man to be as He himself is: Be yet holy for I am holy; man’s own conscience, for how could he otherwise tremble before the divine Being, accuse himself before him, and make him the judge of his inmost thoughts and feelings? (p. 45)

Love is the middle term, the substantial bond, the principle of reconciliation between the perfect and the imperfect, the sinless and sinful being, the universal and the individual, the divine and the human. Love is God himself, and apart from it there is no God. Love makes man God and God man. Love strengthens the weak, and weakens the strong, abases the high and raises the lowly, idealizes matter and materializes spirit. Love is the true unity of God and man, of spirit and nature. In love common nature is spirit, and the preeminent spirit is nature. Love is to deny spirit from the point of view of spirit, to deny matter from the point of view of matter. Love is materialism; immaterial love is a chimæra. (p. 47)

Love plays a major role in Feuerbach. In the chapter “The Mystery of the Incarnation; Or, God as Love, as a Being of the Heart,” he writes:

Who then is our Savior and Redeemer? God or Love? Love; for God as God has not saved us, but Love, which transcends the difference between the divine and human personality. As God has renounced himself out of love, so we, out of love, should renounce God; for if we do not sacrifice God to love, we sacrifice love to God, and, in spite of the predicate of love, we have the God — the evil being — of religious fanaticism. (p. 53)

He concludes the first part of the book with this summary:

Our most essential task is now fulfilled. We have reduced the supermundane, supernatural, and superhuman nature of God to the elements of human nature as its fundamental elements. Our process of analysis has brought us again to the position with which we set out. The beginning, middle and end of religion is Man. (p. 183)

In the second part, Feuerbach goes more on the attack. In the chapter “The Contradiction in the Revelation of God,” he writes:

The Bible contradicts morality, contradicts reason, contradicts itself, innumerable times; and yet it is the word of God, eternal truth, and “truth cannot contract itself.” How does the believer in revelation elude this contradiction between the idea in his own mind, of revelation as divine, harmonious truth, and this supposed actual revelation? Only by self-deception, only by the silliest subterfuges, only by the most miserable, transparent sophisms. Christian sophistry is the necessary product of Christian faith, especially of faith in the bible as a divine revelation. (p. 210)

In the chapter “The Contradiction in the Nature of God in General,” Feuerbach writes:

“It has pleased God” to create a world. Thus man here deifies satisfaction in self-pleasing, in caprice and groundless arbitrariness. The fundamentally human character of the divine activity is by the idea of arbitrariness degraded into a human manifestation of a low kind; God, from a mirror of human nature is converted into a mirror of human vanity and self-complacency. (p. 218)

And in the chapter “The Contradiction of Faith and Love”:

The essence of religion, its latent nature, is the identity of the divine being with the human; but the form of religion, or its apparent, conscious nature, is the distinction between them. God is the human being; but he presents himself to the religious consciousness as a distinct being. Now, that which reveals the basis, the hidden essence of religion, is Love; that which constitutes its conscious form is Faith. Love identifies man with God and God with man, consequently it identifies man with man; faith separates God from man, consequently it separates man from man, for God is nothing else than the idea of the species invested with a mystical form, — the separation of God from man is therefore the separation of man from man, the unloosing of the social bond. By faith religion places itself in contradiction with morality, with reason, with the unsophisticated sense of truth in man; by love, it opposes itself again to this contradiction. Faith isolates God, it makes him a particular, distinct being: love universalizes; it makes God a common being, the love of whom is one with the love of man. Faith produces in man an inward disunion, a disunion with himself, and by consequence an outward disunion also; but love heals the wounds which are made by faith in the heart of man. Faith makes belief in its God a law; love is freedom, — it condemns not even the atheist, because it is itself atheistic, itself denies, if not theoretically, at least practically, the existence of a particular, individual God, opposed to man. Love has God in itself: faith has God out of itself; it estranges God from man, it makes him an external object. (p. 245)

Three times Feuerbach repeats the Latin slogan he popularized (if not quite coined): Homo homini Deus est, man is a god to man (pp. 275, 158, 268):

If human nature is the highest nature to man, then practically also the highest and first law must be the love of man to man. Homo homini Deus est: — this is the great practical principle: — this is the axis on which revolves the history of the world. The relations of child and parent, of husband and wife, of brother and friend, — in general, of man to man, — in short, all the moral relations are per se religious. (p. 268)

Feuerbach especially praises marriage, but not just any marriage: “That alone is a religious marriage, which is a true marriage, which corresponds to the essence of marriage — of love.” (p. 268)

“With the ideas of Feuerbach I everywhere agree,” Marian Evans wrote in a letter (George Eliot Letters, Vol. II, p. 153). Several academics have traced the content of her novels to ideas in Feuerbach. The short article “George Eliot, Feuerbach, and the Question of Criticism” by U. C. Knoepflmacher (Victorian Studies, Vol. 7, No. 3, 1964, pp. 306–309) looks at the use of Feuerbach’s allegorical interpretation of the Last Supper in Adam Bede.

In the article “George Eliot’s Religion of Humanity” (ELH, Vol 29, No. 4, Dec. 19623, pp. 418–443), Bernard J. Paris writes:

The religion of the future, Eliot felt, would be a religion not of God, but of man, a religion of humanity. Feuerbach taught, in fact, that the religions of the past have been truly religions of humanity, but unconsciously so; the religion of the future will consciously worship man. The central preoccupation of George Eliot’s life was with religion, and in her novels, which she thought of as “experiments in life,” she was searching for a view of life that would give modern man a sense of purpose, dignity, and ethical direction. (p. 420)

These two translations were important to Marian Evans’ intellectual development, but were also historically important historically in the Victorian era’s great arc from piety to secularism. With these two translations, “Marian Evans was virtually single-handedly responsible for bringing German Higher Criticism into the English-speaking world and, hence, helping to articulate the Religion of Humanity so prevalent in nineteenth-century discourse.” (Susan E. Hill, “Translating Feuerbach, Constructing Morality: The Theological and Literary Significance of Translation for George Eliot”l, Journal of the American Academy of Religion, Vol. 65, No. 3, Autumn, 1997, pp. 635–653)

Professor Hill then goes on to show how George Eliot constructs “a moral universe without God” in the pages of Middlemarch. Many of the novel’s characters

manifest excessive commitments either to fidelity or creativity in a manner that renders them incapable of participating in a world in which the balance of duty and desire is the basis for moral action. In Feuerbachian terms, they are unable — or unwilling — to see that the ‘gods’ to which they are faithful are human creations. This inhibits them from engaging their commitments in creative, authentic, and morally valid ways. (p. 646)

After the malfocused religious impulses of Dorothea smash up against the Will's dilettantism, the couple “learn to negotiate and balance duty and desire. The Feuerbachian ideal of marriage, a bond created out of love and a model for all moral relations” — and here the writer references Essence of Christianity, page 271 — “is thus translated into the world of Middlemarch through the relationship of Dorothea and Will.” (p. 652)

This Feuerbachian ideal of marriage also influenced Marian Evans' personal life, for soon after her translation of The Essence of Christianity was published, she began living with George Lewes as husband and wife even though they could not legally marry, and Lewes could not legally obtain a divorce. At various times she used the names Marian Evans Lewes, Marian Lewes, and Mrs. Lewes.

Between 1854 and 1856, Marian worked on what was apparently the first English translation of Spinoza’s Ethics, but it was not published in her lifetime and did not see print until 1981. I thought I’d wait for a new edition from Princeton University Press scheduled to appear in January.

Then fiction began appearing under the name George Eliot: the three short stories that comprise Scenes of Clerical Life (1857), her first novel Adam Bede (1859), and the ever popular The Mill on the Floss (1860) and Silas Marner (1861).

Romola (1862–3)

A long time ago, a little village in what is now Italy was beset by plague. Dead bodies lay unburied. Children — some of them Jews recently expelled from Spain or Portugal — wandered parentless in the streets. Suddenly one day, the village was visited by the Madonna who arose from an otherwise deserted ship. Without regard to her own health, she selflessly cared for the sick until the dangers had passed. Then as quickly as she had come, she disappeared and was never seen again.

Many legends were afterwards told in that valley about the Blessed Lady who came over the sea, but they were legends by which all who heard might know that in times gone by a woman had done beautiful deeds there, rescuing those who were ready to perish. (Romola, chapter 68)

The woman was not actually the mother of Jesus, of course. She was a very human (although fictitious) woman from Florence named Romola. Altough some critics and readers don’t care for the section on Romola that I’m alluding to here, it seemed wonderfully magical to me, and (keeping with the Feuerbach theme) shows how human charity can be interpreted in religious terms.

Romola presents something unusual for George Eliot’s readers because for the first time, she leaves her native 19th century English Midlands and travels a thousand miles and over four centuries back in time to Renaissance Florence. She’s not writing about her people, or using the language of her people, which are two of the vital strengths and characteristics of George Eliot as an author. Writing Romola was a risky choice for her, and she knew it.

There does not seem to be a first British edition of Romola on Google Books, but there are Volume 1 and Volume 2 of an international edition created to establish copyright on the Continent, and a one-volume American edition, which doesn't quite compensate for formatting the text into two columns by including 37 illustrations.

I read a Penguin edition that includes an introduction by Dorothea Barrett to help establish the historical background, a glossary of historical figures in the novel, and useful notes. I’ve also seen a Modern Library edition that looked quite good as well. To familiarize myself with the social, religious, and political background, I read Lauro Martines’s informative and entertaining Fire in the City: Savonarola and the Struggle for the Soul of Renaissance Florence, which by coincidence I stumbled upon during one of my periodic sweeps of the Early Modern European History section in Book Culture on 112th Street.

Late 15th century Florence had a framework of a quasi-democratic republican government rather advanced for the era, but in reality, political power was largely in the hands of the de’ Medici family. Despite this authoritarian political control, Florence was regarded as the most civilized city in the Christian world. Religious observances were relaxed, while culture, scholarship. and trade thrived. The residents at the end of the century included Michelangelo and Machiavelli. (Although Leonardo da Vinci was born in Florence, he was no longer there during this time.) The literary heritage of Florence included the famed triumvirate of Dante, Petrarch, and Boccaccio.

Romola begins with the 1492 death of Lorenzo de’ Medici, also known as Lorenzo the Magnificent. (If that date seems vaguely familiar, the second paragraph of the novel mentions the first voyage of Christopher Columbus.) Lorenzo’s heir was the 20-year-old Piero de’ Medici, who was not regarded as capable of inheriting the family dynasty. The political situation was further complicated by an invasion of the French army led by Charles VIII.

Into this vacuum stepped a Dominican friar named Girolamo Savonarola, who advocated a strict religious regimen unfamiliar to the more secular Florentines. As a powerful orator, Savonarola heralded a spiritual awakening and advocated a return to Christian basics. In today’s language, we would call him a “fundamentalist.”

Interestingly, Savonarola did not wish to establish a theocracy. He instead worked to strengthen the democratic and republican institutions of Florence in what we would recognize as a “populist” appeal. The printing press had been introduced to Florence in 1471, and Savonarola used it to distribute his sermons. In Fire in the City, Lauro Martines writes that Savonarola “was almost certainly the most published writer in Italy at the end of the fifteenth century” (page 88) with 108 published items.

Savonarola organized an army of young people who would police the streets and harass people wearing fine clothing, jewelry, or cosmetics. These items were periodically heaped with other luxuries and vanities such as objects of art, non-religious books, games, and playing cards, and everything was burned in big fires called bonfires of the vanities. One of Savonarola’s biographers in the 20th century calls him a “terrorist.”

More politically risky, Savonarola frequently spoke out against the corruption and materialism of the Catholic clergy, and he denounced Pope Alexander VI, but not without cause. Before becoming pope, Alexander VI was known as Rodrigo Borgia, a member of a family that has an infamous reputation to this day. He wasn’t much of a religious leader. He had fathered at least eight children by multiple women (including a daughter named Lucretia Borgia), but because priests and popes are not allowed to have multiple wives — or even just one — all the children were illegitimate.

Perhaps if Savonarola had thrived just a generation later, or survived until that time, he would now be spoken of in the same breath as Martin Luther and John Calvin as the leader of the Italian Reformation . But a campaign against corruption and moral laxity can make a lot of enemies. Savonarola claimed to be a prophet and said he was acting under divine revelation. He was excommunicated in 1497 and the people soon turned against him. With the exception of a brief Epilogue, the historical narrative of Romola ends with Savonarola’s execution in 1498.

Several historical personages step through the pages of Romola, including Savonarola himself, Machiavelli, and lesser-known historical figures. George Eliot provides enough of the historical background that I began wondering if she could have written a non-fiction history imbued with her idiosyncratic literary skill, much like Thomas Carlyle had done with The French Revolution.

The novel begins with a homeless shipwrecked man of Greek origins who had been raised on Italian soil. His name is Tito Melema and he quickly finds his way into the home of a blind scholar named Bardo de’ Bardi. Bardo’s son had gone into the religious life and has become (like Savonarola) a Dominican friar, so only a daughter named Romola (“a tall maiden of seventeen eighteen”) is now able to help him with his studies and his writings. Like all heroines of Victorian novels, of course she is beautiful:

The hair was of a reddish gold colour, enriched by an unbroken small ripple, such as may be seen in the sunset clouds on grandest autumnal evenings. It was confined by a black fillet above her small ears, from which it rippled forward again, and made a natural veil for her neck above her square-cut gown of black rascia, or serge. Her eyes were bent on a large volume place before her: one long white hand rested on the reading-desk, and the other clasped the back of her father’s chair. (ch. 5)

Bardo studies secular literature rather than religious texts. In the scenes with him, we get a picture of a tradition of classical and humanist scholarship that derives much more from the pagan writings of ancient Greece and Rome than from Christianity. This is the kind of intellectual activity that flourished under the de’ Medicis prior to the advent of Savonarola.

Tito’s charm and intelligence allow him to become associated with the movers and shakers of Florence, and he quickly begins wooing Romola. But the reader sees beyond what the characters do. Tito is having a curious relationship with a naïve 16-year-old peasant girl named Tessa that gets more serious when he enters into a sham marriage with her. We also learn that at some point Tito has left behind his adoptive father Baldassarre. Even when Tito gets work that the man is still alive, he is having too much fun in Florence to do anything about it.

What, looked at closely, was the end of all life, but to extract the utmost sum of pleasure? And was not his own blooming life a promise of incomparably more pleasure, not for himself only, but for others, than the withered wintry life of a man who was past the time of keen enjoyment, and whose ideas had stiffened into barren rigidity?... Baldassarre had done his work, had had his draught of life: Tito said it was his turn now. (ch. 11)

Tito’s duplicity will become more evident when the political intrigue begins, for soon arrives in the novel “Fra Girolamo Savonarola, of Ferrara; the prophet, the saint, the mighty preacher, who frightens the very babies of Florence into laying down their wicked baubles.” (ch. 16)

But the real force of demonstration for Girolamo Savonarola lay in his own burning indignation at the sight of wrong; in his fervid belief in an Unseen Justice that would put an end to the wrong, and in an Unseen Purity to which lying and uncleanness were an abomination. To his ardent, power-loving soul, believing in great ends, and longing to achieve those ends by the exertion of its own strong will, the faith in a supreme and righteous Ruler became one with the faith in a speedy divine interposition that would punish and reclaim. (ch. 21)

George Eliot even recreates one of his Savonarola’s sermons, and adds in a note: “The sermon here given is not a translation, but a free representation of Fra Girolamo’s preaching in its more impassioned moments.” Here’s a little taste:

“For the sword is hanging from the sky; it is quivering; it is about to fall! The sword of God upon the earth, swift and sudden! Did I not tell you, years ago, that I had beheld the vision and heard the voice? And behold, it is fulfilled! Is there not a king with his army at your gates? Does not the earth shake with the tread of horses and the wheels of cannon? Is there not a fierce multitude that can lay bare the land as with a sharp razor? I tell you the French king with his army is the minister of God: God shall guide him as the hand guides a sharp sickle, and the joints of the wicked shall melt before him, and they shall be mown down as stubble: He that fleeth of them shall not flee away, and he that escapeth of them shall not be delivered. And the tyrants who make to themselves a throne out of the vices of the multitude, and the unbelieving priests who traffic in the souls of men and fill the very sanctuary with fornication, shall be hurled from their soft couches into burning hell; and the pagans and they who sinned under the old covenant shall stand aloof and say: ‘Lo, these men have brought the stench of a new wickedness into the everlasting fire.’” (ch. 24)

In one of the most amazing scenes, Savonarola confronts Romola directly and persuades her to reconsider a decision that she had made, and by his force of will entices her to become one of his disciples. I suppose it is not much of a plot spoiler to suggest that Romola still has some learning and personal growth ahead of her to discover her own version of the religion of humanity.

Of the five books I’m discussing in this blog entry, this is the one that readers familiar with George Eliot’s other novels will probably enjoy the most. It should not be ignored simply because it doesn’t take place in the English Midlands. I was not disappointed.

The Spanish Gypsy (1868)

The 1860s were not a good time for the Leweses. Both George Lewes and Marian suffered from various illness during this period, and Marian was often depressed, but still she insisted on exploring different approaches to her writing.

The origin of The Spanish Gypsy is a little strange. In Venice she had seen Titian’s Annunciation and in a document she titled “Notes on the Spanish Gypsy and Tragedy in General” (and which was reprinted in John Cross’s biography of her life, 1885, Vol III, p. 42), Marian wrote:

It occurred to me that here was a great dramatic motive of the same class as those used by the Greek dramatists, yet specifically different from them. A young maiden, believing herself to be on the eve of the chief event of her life — marriage — about to share in the ordinary lot of womanhood, full of young hope, has suddenly announced to her that she is chosen to fulfil a great destiny, entailing a terribly different experience from that of ordinary womanhood. She is chosen, not by any momentary arbitrariness, but as a result of foregoing hereditary conditions: she obeys, “Beyond the handmaid of the Lord.” Here I thought is a subject grander than that of Iphigenia, and it has never been used.

Except that George Eliot’s intent was to strip all the supernatural aspects from the story. Rather than the mother of Christ, the character called to a “great destiny” is a young Gypsy woman. Like Romola this book would take place in the 1490s, but in Spain rather than Italy, and against the backdrop of the Spanish-Moorish wars, and the expulsion of Jews and Muslims from Spain by Queen Isabella.

Another big difference separates Romola and this new book. That Marian was doing something risky is revealed in a letter to her publisher, when she warned “The work connected with Spain is not a Romance. It is — prepare your fortitude — a poem.”

Writing this long poem didn’t come easy. It apparently made her so sick that George Lewes had her stop working on it. She shifted her attention back to prose and wrote her novel Felix Holt, the Radical, published in 1866, after which she resumed The Spanish Gypsy and completed it.

The reputation of The Spanish Gypsy is not great. One scholar has written that “The Spanish Gypsy (1868), a long-winded narrative in pedestrian blank verse about the destiny of the gypsy race during the Moorish struggles in Spain, now seems virtually unreadable.” (Miriam Abbott, ”George Eliot in the 1860’s”, Victorian Studies, Vol. 5, No. 2, 1961, pp. 93–108). It is thus approached with great trepidation.

There are other issues: At one point, Marian wanted to write a dramatic poem suitable for the stage, and there are long sections of The Spanish Gypsy with stage directions. But other sections more resemble a narrative poem, and the mix doesn’t quite work. The narrative parts use past tense, but in the dramatic parts, passages that are not part of dialogue are put in square brackets in present tense.

I could not find a copy of the British first edition on Google Books, but they do have the American first edition, and that’s what I’ll be referring to. Apparently the only scholarly edition is an expensive 2008 volume published by Pickering & Chatto, whose 115 pages of textual variants is perhaps more than most readers require. This edition conveniently numbers the lines for easy reference, but the line numbering is found in no other edition. At any rate, the line numbering helps to establish that the poem is 7,127 lines long. The five parts are not of equal length. The first part (which I’ll summarize below) is about 45% of the total poem.

Like Romola, The Spanish Gypsy briefly refers to Columbus:

And so in Córdova though patient nights

Columbus watches, or he sails in dreams

Between the setting stars and finds new day; (page 7)

Christian Spain had been united with the marriage of Ferdinand of Aragón and Isabella of Castille. Spain had mostly defeated but still battled a kingdom of people known as Moors, a term that usually refers to Muslims without any ethnic implication. The poem evokes a time when parts of Spain “’t was Moorish long ago, / But now the Cross is sparkling on the Mosque, / And bells make Catholic the trembling air.” (p. 4) But there are still battles in progress: “The Moslem faith, now flickering like a torch / In a night struggle on this shore of Spain.” (p. 5) Both Muslims and Jews have been expelled from Spain, although Jews who converted to Catholicism were allowed to remain. (There are some Jewish characters.)

Through conversations with several friends, we learn about Duke Silva (also known as Don Silva), who is engaged to marry a young woman. According to Captain Lopez, this fiancée is

One that some say the Duke is ill to wed.

One that his mother reared — God rest her soul! —

Duchess Diana — she who died last year.

A bird picked up away from any nest.

Her name — the Duchess gave it — is Fedalma.

No harm in that. But the Duke stoops, they say,

In wedding her. And that’s the simple truth. (p. 28)

Don Silva’s fiancée is Fedalma, and her mysterious origins will not be much of a mystery to anyone who has read the poem’s title. Captain Lopez has nothing against her personally, yet there is gossip:

I think no harm of her; I thank the saints

I wear a sword and peddle not in thinking.

‘T is Father Marcos says she’ll not confess

And loves not holy water; says her blood

Is infidel; says the Duke’s wedding her

Is union of light with darkness. (p. 30)

Lopez also has some news about Gypsies who had been aiding the Moors and had been captured in battle: “There is strict command / That all our gypsy prisoners shall to-night / Be lodged without the fort.” Among the Spaniards, there is not high regard for these Gypsies: “Some say, the Queen / Would have the Gypsies banished with the Jews. / Some say, ‘t were better harness them for work. / They’d feed on any filth and save the Spaniard.” (p. 36) There is similar regard among these anti-Semitic Spaniards to Jews. As one says:

Jews are not fit for heaven, but on earth

They are most useful. ‘T is the same with mules,

Horses, or oxen, or with any pig

Except Saint Anthony’s. They are useful here

(The Jews, I mean) though they may go to hell. (p. 37)

The origin of the Gypsies is mysterious to these Spaniards (as it was to the Gypsies themselves during this time). One convenient but absurd theory is that the Gypsies originated 1500 years earlier when God “sent the Gypsies wandering / In punishment because they sheltered not / Our Lady and Saint Joseph (and no doubt / Stole the small ass they fled with into Egypt)…” (p. 37)

Our introduction to Don Silva’s fiancée Fedalma occurs when music is being played in the public square and she makes a dramatic entrance:

Sudden, with gliding motion like a flame

That through dim vapor makes a path of glory,

A figure lithe, all white and saffron-robed,

Flashed right across the circle, and now stood

With ripened arms uplift and regal head,

Like some tall flower whose dark and intense heart

Lies half within a tulip-tinted cup.

…

“Lady Fedalma! — will she dance for us?” (p. 49)

And she does, wondrously and scandalously:

Swifter now she moves,

Filling the measure with a double beat

And widening circle; now she seems to glow

With more declaréd presence, glorified.

Circle, she lightly bends and lifts on high

The multitudinous-sounding tambourine,

And makes it ring and boom, then lifts it higher

Stretching her left arm beauteous; now the crowd

Exultant shouts, forgetting poverty

In the right moment of possessing her. (p. 53)

But then the Gypsy prisoners are led through the square, chained two-by-two except for their chief. He turns to face Fedalma, and everything stops. Is there some kind of connection between them? She “stands / With level glance meeting that Gypsy’s eyes, / That seem to her the sadness of the world / Rebuking her … Why does he look at her? Why she at him? / As if the meeting light between their eyes / Made permanent union?” (p. 54)

Meanwhile, a character known as the Prior tries to convince Don Silva not to marry Fedalma. He calls her an “infidel,” but Don Silva pleads that she is not: “Fedalma is no Jewess, bears no marks / That tell of Hebrew blood.” (p. 63) The Prior seems to know something he does not:

She bears the marks

Of races unbaptized, that never bowed

Before the holy signs, were never moved

By stirrings of the sacramental gifts. (p. 63)

Moreover, she has been seen dancing in public: “She has profaned herself. Go, raving man, / And see her dancing now. Go, see your bride / Flaunting her beauties grossly in the gaze / of vulgar idlers…” (p. 66) When Don Silva confronts Fedalma, she pleads that her dancing was a symbol of their love:

Yes, it is true. I was not wrong to dance.

The air was filled with music, with a song

That seemed the voice of the sweet eventide, —

The glowing light entering through eye and ear, —

That seemed our love, — mine, yours, — they are but one, —

Trembling through all my limbs, as fervent words

Tremble within my soul and must be spoken.

And all the people felt a common joy

And shouted for the dance. A brightness soft

As of the angles moving down to see

Illumined the broad space. The joy, the life

Around, within me, were one heaven: I longed

To blend them visibly: I longed to dance

Before the people, — be as mounting flame

To all that burned within them! Nay, I danced;

There was no longing: I but did the deed

Being moved to do it. (pp. 70–1)

They talk about the captured man she saw. Fedalma says “O Silva, such a man! I thought he rose / From the dark place of long-imprisoned souls, / To say that Christ had never come to them.” (p. 74) Don Silva tells her “they are Gypsies, strong and cunning knaves, / A double gain to us by the Moors’ loss: / The man you mean — their chief — is an ally / The infidel will miss.” (p. 74) Don Silva gives her presents of jewelry as they discuss their plans to wed the next day. He praises her: “Not Queen Isabel / Will be a sight more gladdening to men’s eyes / Than my dark queen Fedalma.” (p. 84)

The Prior has plans of his own. His job is to prevent the marriage:

This spotless maiden with her pagan soul

Is the arch-enemy’s trap: he turns his back

On all the prostitutes, and watches her

To see her poison men with false belief

In rebel virtues. She has poisoned Silva… (p. 98)

…

The maiden is the cause, and if they wed,

The Holy War may count a captain lost.

For better he were dead than keep his place,

And fill it infamously: in God’s war

Slackness is infamy. (p. 99)

…

To-morrow morn this temptress shall be safe

Under the Holy Inquisition’s key. (p. 101)

In 1490s Spain, nobody should not expect the Spanish Inquisition.

At this point, it is probably not a plot spoiler to reveal that the evening before her wedding, Fedalma is visited by the Gypsy chief, whose name is Zarca and who has escaped from captivity. He reveals that he is her father. In an amusing subversion of cultural stereotypes, it turns out that she had been stolen from from the Gypsies.

I lost you by a trivial accident.

Marauding Spaniards, sweeping like a storm

Over a spot within the Moorish bounds,

Near where our camp lay, doubtless snatched you up…

‘T was so I lost you, — never saw you more

Until to-day I saw you dancing! Saw

The child of the Zincalo making sport

For those who spit upon her people’s name…

Therefore I am come — to claim my child,

Not from the Spaniard, not from him who robbed,

But from herself. (p. 106, 107)

Fedalma is astonished at this news: “Then . . . . I am . . . . a Zincala? … Of a race / More outcast and despised than Moor or Jew?” (p. 108) He responds:

Yes: wanderers whom no God took knowledge of

To give them laws, to fight for them, or blight

Another race to make them ampler room;

A people with no home even in memory,

No dimmest lore of giant ancestors

To make a common hearth for piety. (p. 108)

Zarca now wants his daughter to help “guide my brethren forth to their new land.” (p. 112). Fedalma prefers to marry first before revealing that the Gypsy chief is her husband’s new father-in-law, but Zarca rejects that. He tells her “you shall be a queen in Africa,” (118) which is suggested as the Gypsies’ homeland. “You belong / Not to the petty round of circumstance / That makes a woman’s lot, but to your tribe.” (p. 119) Zarca calls her his Queen and she agrees to go with him, leaving everything behind:

Stay, my betrothal ring! — one kiss — farewell!

O love, you were my crown. No other crown

Is aught but thorns on my poor woman’s brow. (p. 125)

End of Book I.

I found The Spanish Gypsy to be somewhat disorienting on my first read. I didn’t quite understand why I was being introduced to characters who might or might not play a larger role in what was to come. The second time through, though, it all made a lot more sense, and it emerged as exciting epic poetry.

What I missed most was the depth of character exploration normally associated with George Eliot’s work. The verse form seems to work against that, although it is chock full of conflicts, both internal and external. One critic summarizes:

Conceived as stage drama, quickly converted to closet drama, always leaning towards opera, the augmentations of stage direction and third-person narration with novelistic intradiegesis and four explanatory endnotes establish the poem as a technical mélange whose transgressions and minglings do not parallel the message of ethnic separation delivered as its ostensible message. (Kathleen McCormack, “The Spanish Gypsy: Geography, Photography, and Ethnography in Spain”, George Eliot – George Henry Lewes Studies, No. 60/61, 2011, pp.47–61)

Still, it’s a shame that there isn’t a Penguin or Oxford World’s Classics edition.

Impressions of Theophrastus Such (1879)

One article I read in preparation for this blog entry speculated about George Eliot’s reputation had she had stopped writing after publication of The Spanish Gypsy. Fortunately she did not, and after the tough times of the 1860’s, she wrote her two most sophisticated and complex novels, Middlemarch (1871–72), commonly regarded as one of the towering masterpieces of English literature, and Daniel Deronda (1876). This latter novel has a connection with The Spanish Gypsy when the title character discovers that he is Jewish, and very likely descended from Jews expelled from Spain in 1492.

Daniel Deronda is usually referred to as George Eliot’s last novel, but in 1879, another book was published that is certainly fiction, but too long to be a short story or novella. So what is it?

The year 1879 possibly qualifies as “late Victorian” and look around at what’s going on: Thomas Hardy has already written Far from the Madding Crowd and The Return of the Native. That’s the year of George Meredith’s The Egoist and of Gilbert & Sullivan’s Pirates of Penzance, and a young aesthete has just graduated from Oxford and is preparing to become Oscar Wilde.

Which means that we might perhaps expect something experimental from George Eliot, and in Impressions of Theophrastus Such, this is what we get.

I haven’t been able to find the British first edition of Impressions of Theophrastus Such on Google Books, but the American first edition is available. In 1994, the University of Iowa Press published an edition with an exceptionally useful introduction and notes by Nancy Henry, but there’s not a trace of this book on their web site. Used copies are available from the usual sources.

First, the weird title: The original Theophrastus was a philosopher of Ancient Greece who was said to be a favorite student of Aristotle’s. His real name was Tyrtamus, but Aristotle awarded him a name that proclaims his divine sweetness of speech. In Lives of the Ancient Philosophers, Diogenes Laertius lists over 200 books that Theophrastus wrote. Only a handful still survive.

Theophrastus is today most famous for his book Characters, which was probably written about 320 B.C. The book consists of 30 sketches of unpleasant character types likely to be found in Athens during this era — as well as every other society throughout time. In 1870 a friend of the Leweses had translated Characters into English. Perhaps this English translation by Robert Claverhouse Jebb with the original Greek text is what gave Marian the idea for her book, although it is quite different. Here’s part of Webb’s translation of The Gross Man:

The Gross man is one who will insult freeborn women; who, in a theatre, will applaud when others cease, and hiss the actors who please the rest of the spectators. When the Marketplace is full, he will go up to the place where nuts or myrtleberries or fruits are sold, and stand munching while he chatters to the seller. Then he will call by name to a passer-by with whom he is not familiar; or if he chance to see persons in a hurry, he will cry ‘stop’; or he will go up to a man who has lost a great lawsuit and is leaving the court, and will congratulate him. (p. 127)

Much more recently, an entertaining rendition published by Callaway features a translation by Pamela Mensch adorned with witty illustrations. Here’s part of her translation of the same passage, now titled The Obnoxious Man. See if you can catch examples of the infamous Victorian reticence to discuss body parts and bodily functions:

The Obnoxious man is the sort who, when he encounters freeborn women, pulls up his clothes and flashes his genitals. In the theater he applauds when everyone else has stopped, and hisses actors whom the rest of the audience take pleasure in watching; and when the audience is silent, he throws back his head and belches to make the spectators turn around. When the marketplace is crowded he visits the shops that sell nuts, myrtle berries, and fruits, and munches on these items while chatting with the seller. He hails by name a bystander with whom he’s not acquitted. When he sees people in a hurry to get somewhere, he urges them to wait. He goes up to a man who’s leaving the law court after losing an important case and congratulates him. (p. 51)

What does the word Such mean in the title Impressions of Theophrastus Such? According to Nancy Henry in her introduction to the University of Iowa Press edition, the Greek versions of Theophrastus’s character sketches all include the phrase toiontos tis, hoios, which can be translated as “such a type who,” which means that the title of George Eliot’s book suggests “Impressions of Theophrastus, Such a Type Who…” (page xviii) However, this conjecture is refuted by a review of this edition in the journal Criticism.

The first word of the title, Impressions could refer to printed pages of a book, emphasizing the self-referential character of this work.

The narrator of this book does not refer to himself by name, however. We know he is a bachelor and tells us that he is often described as “the author of a book you have probably not seen.” He cannot resist writing for what he imagines as “a far-off, hazy, multitudinous assemblage, as in a picture of Paradise, making an approving chorus to the sentences and paragraphs of which I myself particularly enjoy the writing.” (chapter I) This narrator as a separate individual (apart from George Eliot the author) fades in an out of the book. There is an ambiguity over whether we’re reading the words of a cantankerous fictional narrator or a cantankerous actual author, and it's not necessarily a playful ambiguity.

Regardless, whoever is writing these 18 loosely related quasi-fictional essays — mostly about writers and writing —tends to be rather long-winded and at time exhausting. What the narrator has to report is sometimes trivial and at other times crucial. In this passage, perhaps we can still relate to the idea of people being bullied, abused, and even tortured in print:

The serene and beneficent goddess Truth, like other deities whose disposition has been too hastily inferred from that of the men who have invoked them, can hardly be well pleased with much of the worship paid to her even in this milder age, when the stake and rack have ceased to form part of her rituals. Some cruelties still pass for service done in her honour: no thumb-screw is used, no iron boot, no scorching of flesh; but plenty of controversial bruising, laceration, and even lifelong maiming. Less than formerly; but so long as this sort of truth worship has the sanction of a public that can often understand nothing in controversy except personal sarcasm or slandering ridicule, it is likely to continue. The sufferings of its victims are often as little regarded as those of the sacrificial pig offered to old time, with what we now regard as a sad miscalculation of effects. (ch. III)

Thus begins a story of young scholar who is inspired to write a book that dares to question the theories of one of the famous authorities on the subject. His book is viciously attacked in the periodicals, and his career is trashed. After much time passes, his theories are fully accepted by his opponent but with no acknowledgement to himself. The punchline, however, is the title of this chapter: “How We Encourage Research.”

Yet the narrator of Impressions is just as quick to lay waste to writers whose aspirations are greater than their talents. In Chapter XIV, “The Too Ready Writer,” a man named Pepin is described who has “made for himself a necessity of writing (and getting printed) before he had considered whether he had the knowledge or belief that would furnish eligible matter.” Sometimes his ambitions exceed his industry:

He once asked me to read a sort of programme of the species of romance which he should think it worth while to write — a species which he contrasted in strong terms with the productions of illustrious but overrated authors in this branch. Pepin’s romance was to present the splendours of the Roman Empire at the culmination of its grandeur, when decadence was spiritually but not visibly imminent: it was to show the workings of human passion in the most pregnant and exalted of human circumstances, the designs of statesmen, the interfusion of philosophies, the rural relaxation and converse of immortal poets, the majestic triumphs of warriors, the mingling of the quaint and sublime in religious ceremony, the gorgeous delirium of gladiatorial shows, and under all the secretly working leaven of Christianity.

Alas, we then learn what he will exclude from this epic, and become convinced that he’s not quite conceived a masterpiece:

Such a romance would not call the attention of society to the dialect of stable-boys, the low habits of rustics, the vulgarity of small schoolmasters, the manners of men in livery, or to any other form of uneducated talk and sentiments: its characters would have virtues and vices alike on the grand scale, and would express themselves in an English representing the discourse of the most powerful minds in the best Latin, or possibly Greek, when there occurred a scene with a Greek philosopher on a visit to Rome or resident there as a teacher.

Even in historical fictions like Romola, it is George Eliot’s concern with the common people that elevates her fiction. Yet Pepin figures that by focusing only on the grandiose he can achieve greatness:

In this way Pepin would do in fiction what had never been done before: something not at all like [Edward Bulyer-Lytton’s] ‘Rienzi’ or [Victor Hugo’s] ‘Notre Dame de Paris,’ or any other attempt of that kind; but something at once more penetrating and more magnificent, more passionate and more philosophical, more panoramic yet more select: something that would present a conception of a gigantic period; in short, something truly Roman and world-historical.

Yet, the next chapter “Diseases of Small Authorship,” I found mean-spirited. This is about a woman who has written just one book entitled The Channel Islands, with Notes and an Appendix, and never lets an opportunity go by to prod people into reading it and giving her their opinion.

Poor Vorticella might not have been more wearisome on a visit than the majority of her neighbours, but for this disease of magnified self-importance belonging to small authorship. I understand that the chronic complaint of ‘The Channel Islands’ never left her. As the years went on and the publication tended to vanish in the distance for her neighbours’ memory, she was still bent on dragging it to the foreground, and her chief interest in new acquaintances was the possibility of lending them her book, entering into all details concerning it, and requesting them to read her album of ‘critical opinions.’ This really made her more tiresome than Gregarina, whose distinction was that she had had cholera, and who did not feel herself in her true position with strangers until they knew it. (ch. XV)

The final three chapters take on more serious subjects and tone. The chapter on “Moral Swindlers” begins with a punch:

It is a familiar example of irony in the degradation of words that ‘what a man is worth’ has come to mean how much money he possesses; but there seems a deeper and more melancholy irony in the shrunken meaning that popular or polite speech assigns to ‘morality’ and ‘morals.’

And here it seems that George Eliot is herself speaking when she complains that politicians and businessmen are apt to be termed by the public as “moral” if they are “good family men,” without regard to the hideous effects of their pernicious policies or business practices.

Until we have altered our dictionaries and have found some other word than morality to stand in popular use for the duties of man to man, let us refuse to accept as moral the contractor who enriches himself by using large machinery to make pasteboard soles pass as leather for the feet of unhappy conscripts fighting at miserable odds against invaders: let us rather call him a miscreant, though he were the tenderest, most faithful of husbands, and contend that his own experience of home happiness makes his reckless infliction of suffering on others all the more atrocious. (ch. XVI)

The final chapter of Impressions is the most serious, for it address the pervasive horrendous problem of anti-Semitism in 19th century England. The title “The Modern Hep! Hep! Hep!” alludes to anti-Semitic violence targeting Ashkenazi Jews in Bavaria in 1819. Where the word “hep” comes from is uncertain. It could be the cry of German sheepherders, or an acronym of the Latin “Hierosolyma est Perdita” (“Jerusalem is lost”) said to be used during the Crusades. “The Modern Hep! Hep! Hep!” is a condemnation of anti-Semitism among the English during the period of this book.

George Eliot is commonly regarded as one of the more liberal and enlightened exceptions to the anti-Semitism of her era. Daniel Deronda is a sympathetic portrait of Jews, and the title character is even categorized by modern critics as a “proto-Zionist” in seeming to presciently anticipate the later Zionist movement. Zionism was a response to anti-Semitic attacks later in the 19th century, including the Dreyfus affair, which Theodor Herzl said was an influence on his desires to found a Jewish state.

But it is not so clear cut George Eliot emerges as an unblemished hero in the battles against anti-Semitism. As Susan Meyer notes in an article entitled “’Safely to Their Own Border’: Proto-Zionism, Feminism, and Nationalism in Daniel Deronda” (ELH, Vol. 60, No. 3, Autumn 1993, pp. 733–758), the type of proto-Zionism that Daniel Deronda represents was not uncommon in England, and represented more of an impulse to rid the country of Jews — much like the colonization efforts in the antebellum United States. In contrast, a defense of this chapter can be found in K. M. Newton’s “George Eliot and Racism: How Should One Read ‘The Modern Hep! Hep! Hep!’? (The Modern Language Review, Vol. 103, No. 3, 2009, pp.654–665), in which the George Eliot's deeper views are distinguished from the fictional pleas in her book.

To the modern reader, the penultimate chapter might be the most intriguing. The title of Chapter XVII, “Shadows of the Coming Race,” alludes to Edward Bulyer-Lytton’s 1871 novel The Coming Race. In this novel, the narrator descends deep in the earth to discover a distinct species of people living in an advanced society. Through development of a destructive weapon involving a powerful electricity-like substance call Vril, they have succeeded in eliminating strife and competition, and creating a world of peace and leisure. They have many conveniences, such as aerial boats, lifelike automata servants, and three-year marriage contracts. The narrator realizes that if this underground race ever came into conflict with us humans above ground, they would win and become the dominant race of intelligent beings.

The narrator of Impressions of Theophrastus Such seems most concerned by the mechanistic aspects of future societies. One of the narrator’s friends “always tries to keep up my spirits under the sight of the extremely unpleasant and disfiguring work by which many of our fellow-creatures have to get their bread, with the assurance that ‘all this will soon be done by machinery.’” The narrator begins to be nervous about the long-term direction of this automation.