Elliott Carter’s Seventies (1979 – 1988)

December 9, 2008

New York, N.Y.

In his seventies, Elliott Carter increasingly focused on smaller ensembles and began giving his works more sensually evocative names, such as Night Fantasies and Enchanted Preludes rather than the more generic Piano Sonata or Duet for Flute and Cello. During this period Carter composed three works for solo instruments (piano, guitar, violin), two duets (for flute and clarinet, and for flute and cello), a new string quartet (of course), and several works for chamber ensembles.

Missing from the works of this decade is anything for a full symphony orchestra.

That perception is not entirely accurate, however. Carter actually wrote two short orchestral works during this decade that later became part of Three Occasions, which was completed during Carter's eighties. But Carter's shift away from the symphony orchestra is very real, and it was partly a very practical one:

Following the heyday of contemporary music performances in the 1960s and 1970s, an increased conservatism and timidity seemed to characterize symphony orchestras in the 1980s and later years, particularly in the United States, and as the audience has aged, this trend has gotten worse and worse. Orchestras are now deathly afraid of offending what little audience they have left, and if these orchestras have been reluctant to commission or program new works by Elliott Carter, there is little incentive for Carter to write them.

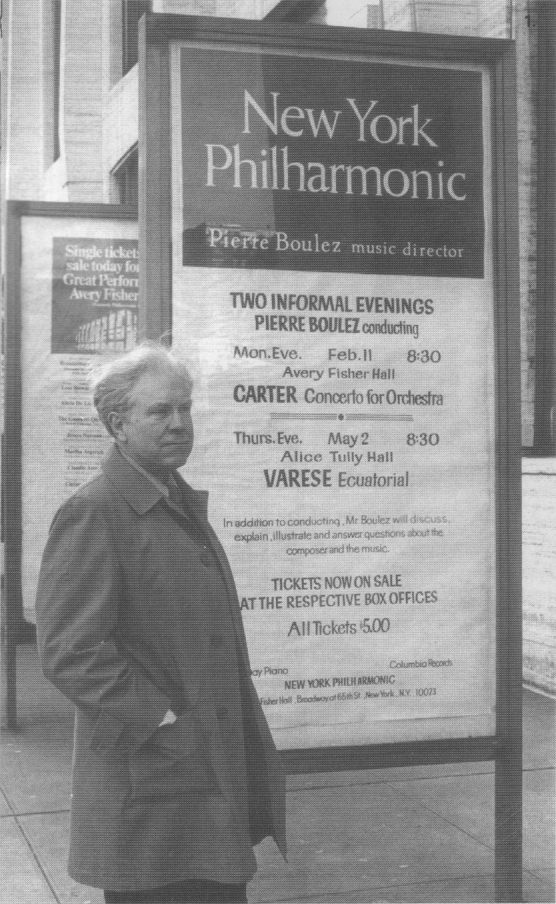

It didn't have to be like this, and the New York Philharmonic under the Music Directorship of Pierre Boulez during the years 1971 to 1977 showed a clearly different approach. Boulez was (and remains) a great champion of 20th century and contemporary music, and he felt it was his obligation to educate and enlighten the New York City audience in a variety of different ways — not least of which was his ability to deliver first rate performances of difficult works.

Elliott Carter outside Avery Fisher Hall, 1973

Photo by Nancy Crampton printed in the Carnegie Hall Playbill, December 2008

During Boulez's reign, the New York Philharmonic seemed to acquire a new enthusiastic young audience as eager to hear Messiaen, Varèse, and Carter as Bach and Beethoven. (I know this because I was one of them; my college years just across the Hudson River coincided with the first four years of Boulez at the Philharmonic.) Pierre Boulez demonstrated that music was still a vibrant exciting living force, and not something that suddenly disappeared just prior to 1913.

Pierre Boulez had shown what could be done, but after he left New York City in 1977, few others seemed to match his tenacity and courage, and many American cities had not benefited from a Pierre Boulez at all. How bad has the situation gotten? Well, in two days, America's pre-eminent composer will celebrate his 100th birthday, yet some American orchestras (here's one chosen not quite at random) are entirely ignoring this unprecedented event out of pure fear that some of their audience might hear a few tunes they can't quite hum. This is not just irresponsible. It is suicide.

Elliott Carter's 24-minute Night Fantasies (1980) was his first work for piano since the Piano Sonata of 1946 and was dedicated to Paul Jacobs, Gilbert Kalish, Ursula Oppens, and Charles Rosen, all well-known pianists with a particular interest in Carter's work. As befitting the title, the work begins with slow eerie chords, but it is not Carter's habit to stick to a particular mood, and the music unfolds with many contrasting sections that contribute to a feeling of wandering free association. It almost sounds — and this is rare for a Carter work — improvised.

Night Fantasies is a popular work and seven different recordings are currently available on CD, including two by Ursula Oppens, but Paul Jacobs' old recording for Nonesuch Records has regrettably not been made available on CD.

In Sleep, In Thunder (1981), a 21-minute song cycle of six poems of Robert Lowell for tenor and chamber orchestra, is a complement of sorts to A Mirror on Which to Dwell, composed just six years earlier to six poems by Elizabeth Bishop, but can also be viewed as the conclusion of a trilogy of American poetry that includes Syringa, with a text by John Ashbery. The instrumentalists don't exactly accompany the singer but rather provide commentary and punctuation, sometimes opposition, sometimes comfort. I particularly like the setting of "Careless Night," with comparatively sparse instrumentation, often a flittering flute, building as almost each word becomes a strain to enunciate.

As the title suggests, Triple Duo (1982) is for six instrumentalists divided into duos of flute and clarinet, percussion and piano, violin and cello. Carter characterized this 19-minute work as "quirky" and "comic" (The Music of Elliott Carter, p. 124) and at least the fast parts sometimes sound to me like a wild dance of three partners, each periodically trying to steal the spotlight and often bumping into one other.

The 7-minute Changes (1983), composed for David Starobin, is Carter's first work for solo guitar, although he had used the guitar to accompany a singer in the 1938 song Tell Me Where is Fancy Bred and it also shows up in some later chamber works, including Syringa. Changes has much varied guitar playing ranging from violent strums to soft picks.

Elliott Carter wrote several even shorter works during this decade to celebrate birthdays and other events. Canon for 4 (1984) is a 3' 45" quartet for flute, bass clarinet, violin, and cello written for William Block on his retirement from the Bath Music Festival. I love the sound of this combination of instruments and the intricate structure of the canon.

Riconoscenza ("gratitude") per Goffredo Petrassi (1984) commemorated the Italian composer's 80th birthday. (Petrassi died in 2003 at the age of 98.) This is Carter's first composition for solo violin, a generally slow, gentle work punctuated with more active passages. (Although the score indicates that the length is 3 minutes, the three recordings I've checked range from 4½ to 6½ minutes.)

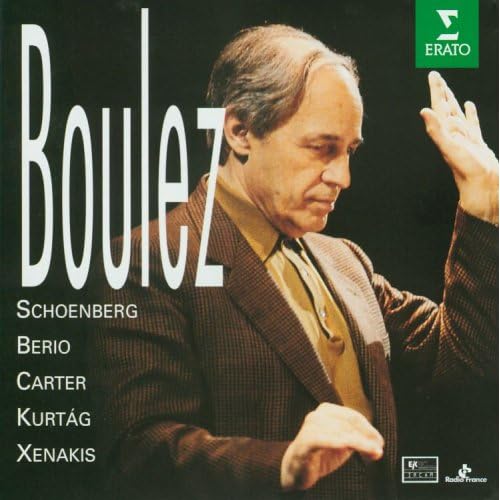

Carter wrote the 4-minute esprit rude / esprit deux (1984) for flute and clarinet "Pour Pierre Boulez en célébration de son soixantième anniversaire," although Boulez didn't really turn 60 until the following year when the work was premiered.

Carter gave this piece an amusingly Boulezian title with trademark lowercase and slash — it actually translates as the "rough-breathing" and "smooth-breathing" characteristics of classical Greek pronunciation — and some Boulezian sounds, including long held notes that suddenly break into fast sequences.

Carter also dedicated a much more substantial work, Penthode (1985) to Pierre Boulez, who conducted its first performance. This concept of this 18-minute work is rather like Triple Duo, only more so, featuring five groups of four instruments each. One might expect a corresonding increase in frenzy, but this is not so. Penthode is a particularly contemplative work for most of its duration, with much opportunity for lyrical solo passages.

(The CD I have of Penthode is an Apex release that I found in the Imports bin at J&R. The CD also includes the Oboe Concerto, esprit rude / esprit deux, and A Mirror on Which to Dwell played by the Ensemble InterContemporain under the direction of Pierre Boulez. It's definitely worth trying to track down.)

As usual, Elliott Carter reserves some of his most complex compositional writing for the string quartet, and the 24½ minute String Quartet No. 4 (1985) is as different from its predecessors as they are from each other. Part of that difference is an extremely conventional overall structure: four movements of about equal length titled Appassionato, Scherzando, Lento, and Presto. However, the movements are played without breaks, and the music is anything but conventional. This is a very dense work, particularly in the outer movements, with the Lento certainly the easiest to follow.

Carter wrote the 20-minute Oboe Concerto (1987) for Heinz Holliger. The accompanying chamber orchestra includes strings, four wind instruments, and two percussionists, but it sounds almost as fat as a full symphony. This is an exciting work, with the oboe and orchestra in constant contrast, and the oboe performing tricks that Holliger taught to Carter (who was himself an oboe student many years ago) during his active assistance during the concerto's composition.

The 6-minute Enchanted Preludes (1988) for flute and cello was commissioned by Harry Santen for the 50th birthday of his wife Ann Santen, who was director of a public radio station in Cincinnati that played a lot of contemporary music. It is tempting to identify the two instruments with the husband and wife, and while the two instruments don't play in unison, they toss thematic material back and forth in a bewitchingly manner.

Carter also wrote a birthday tribute for his own wife Helen, but the 1-minute Birthday Flourish (1988) for brass quintet has never been recorded.

(More detailed descriptions of Carter's music can be found in David Schiff's The Music of Elliott Carter, second edition, Cornell University Press, 1998. Recordings of many of the compositions I've mentioned can be purchased from the Elliott Carter page at ArkivMusic.com. Bridge Records has released seven CDs of Elliott Carter's works that are essential sources for his music of the last three decades.)