Elliott Carter’s Forties (1949 – 1958)

December 4, 2008

New York, N.Y.

Elliott Carter dated his Sonata for Violoncello and Piano December 11, 1948, his 40th birthday, perhaps aware that this work would initiate a new path for his music over the course of the next decade. In his 40's, Carter published only four works totalling less than two hours of music, but nothing here is superfluous.

Although Carter would never again write music with the comparatively simple harmonies and rhythms of works such as the Symphony No. 1, he hadn't quite left neoclassicism behind. The Eight Etudes and a Fantasy (1949) for flute, oboe, clarinet and bassoon, originated as examples in a course on orchestration that Carter was teaching at Columbia University. This is a delightful little work: The etudes are short, ranging in length from a minute to two-and-a-half minutes, most based on simple material. In the second etude, for example, a single chord is played for the duration, with different instruments moving in and out of its structure. The third etude is built entirely from a two-note figure tossed around from instrument to instrument. In the seventh etude the instruments play nothing but a G.

The real surprise is at the end. After the eight etudes, the Fantasy begins, and of course we expect something free-form and improvisatory, but the solo eight-bar opening theme of the clarinet sounds oddly like the beginning of... Could it be?... And yes, when the bassoon enters playing the same theme, we know we're in the middle of a fugue. But when the flute enters as the third voice, it suddenly shifts gears and becomes more like the Fantasy we were expecting (or not expecting), as pieces of the previous etudes (and the fugue theme) come together to play.

In 1950 Carter made a temporary move to the desert near Tucson, Arizona, and in the fall and winter of that year continuing into the spring of 1951, he wrote his String Quartet No. 1 (1951):

-

I decided for once to write a work very interesting to myself, and so say to hell with the public and with the performers too. I wanted to write a work that carried out completely the various ideas I had at that time about the form of music, about texture and harmony — about everything. (quoted in The Music of Elliott Carter, 55)

Carter's five string quartets are among his most important compositions, as essential and as revolutionary as the late string quartets of Beethoven and the six string quartets of Bartok. They are all structured in radically different ways. This first quartet seems to have the traditional four movements, labeled Fantasia, Allegro scorrevole, Adagio, and Variations but these movements flow into one other, and the only breaks in the music are in the middle of the second and last movements, which seems to separate the composition into three parts.

One might think that a stint in the desert might have caused the composer to write a sparse, quiet work, but Elliott Carter's String Quartet No. 1 is easily the most complex music he had written so far. There is a great deal of activity in this work, often several things going on at the same time, and much of it so fast you can't even get a good feel for the rhythms. Yet it never sounds chaotic — at least in the recorded versions I've heard; I suspect a bad performance would be truly a mess — and is instead thrilling and exhilarating with a gorgeous fade-out ending.

The string quartet is of coursey the most common chamber music ensemble since the days of Haydn. But a quartet consisting of flute, oboe, cello, and harpsichord is very unusual. The harpsichord was a staple of the baroque and early classical period (and shows up in the home of every proper young lady in mid-18th century novels such as Tom Jones and Clarissa) but it was largely supplanted by the louder and more pliable piano in the 19th century. In the 20th century, however, the harpsichord made a comeback when performers such as Wanda Landowska and Sylvia Marlowe popularized it for playing the music of Bach, Scarlatti, and other Baroque and early-Classical composers.

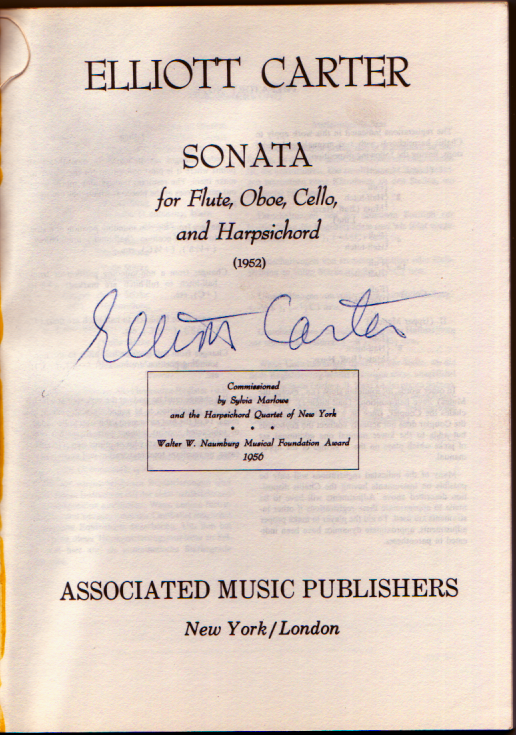

Sylvia Marlowe — who was born in 1908 a few months before Elliott Carter but died in 1981 — became professor of harpsichord at the Mannes College of Music in New York in 1948. She commissioned contemporary composers to write new works for the harpsichord, and this is how Elliott Carter came to write his Sonata for Flute, Oboe, Cello, and Harpsichord (1952).

Score autographed by the composer after a concert probably in November 1974

Carter's sonata has a traditional three-movement fast-slow-fast form, with the movements labeled Risoluto ("bold"), Lento, and Allegro. When listening to this piece, it is always a little startling to discover anew how quiet the harpsichord is when conbined with more modern instruments. In the concertos of Bach, the harpsichord is often in the background playing the continuo part. However, Carter doesn't attempt to mimic Baroque harpsichord playing. Briefly at the beginning the harpsichord seems buried and it pounds out a furious refusal, but soon the other instruments get rather softer to give it some room, particularly in the lovely slow second movement, when the harpsichord alternates with the wind instruments until joining in a fast middle section.

(Although I'm avoiding recommending specific recordings in these blog entries, one essential CD is the Elektra Nonesuch release of both of Carter's harpsichord works with the late Paul Jacobs at the harpsichord, coupled with Paul Jacobs on piano for the Sonata for Violoncello and Piano.)

Everything that Carter had been working on this decade came together in the Variations for Orchestra (1955). In days gone by, the variation form was a particular favorite of music listeners because it was fairly easy to follow. (See Benjamin Britten's Variations and Fugue on a Theme of Purcell, a.k.a., Young Person's Guide to the Orchestra.) So the first question is: How well can one discern the actual theme and variations in Variations for Orchestra? I'm afraid Carter doesn't make it easy. The work begins with an Introduction, so it's not quite clear when the Theme actually begins or ends. Sometimes the variations appear in bits and pieces before their proper beginnings, and only a few times does Carter insert actual breaks between the individual variations.

Fortunately, some kind soul at New World Records inserted CD index markings to accompany the recording by Michael Gielen and the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra:

| Index | Time | Section |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0:00 | Introduction. Allegro |

| 2 | 0:56 | Theme. Andante |

| 3 | 3:05 | Variation 1. Vivace leggero |

| 4 | 4:06 | Variation 2. Pesante |

| 5 | 6:21 | Variation 3. Moderato |

| 6 | 7:52 | Variation 4. Ritardando molto |

| 7 | 8:43 | Variation 5. Allegro misterioso |

| 8 | 9:48 | Variation 6. Accelerando molto |

| 9 | 11:35 | Variation 7. Andante |

| 10 | 13:54 | Variation 8. Allegro giocoso |

| 11 | 14:53 | Variation 9. Andante |

| 12 | 16:47 | Finale. Allegro molto |

The second column shows the track time corresponding to these indices in case you have a CD player that doesn't show index markings.

Notice the 4th and 6th variations: These sections continuously slow down and speed up, respectively, which is a technique that Carter will use in later compositions. And to answer my earlier question: Yes, with a little practice, you can hear the variations, or at least get a vague idea of what's going on, and nevertheless completely enjoy the raucous finale.

(More detailed descriptions of Carter's music can be found in David Schiff's The Music of Elliott Carter, second edition, Cornell University Press, 1998. Recordings of many of the compositions I've mentioned can be purchased from the Elliott Carter page at ArkivMusic.com.)