Reading “Little Dancer Aged Fourteen”

January 30, 2019

Sayreville, New Jersey

I've always been both fascinated and disturbed by Degas' paintings of young ballerinas. The tutus are so frilly, the legs and arms exquisitely posed even when they're not dancing, but the faces are often turned away from us, and when we do see their faces, they are deliberately smudged, or appear pained, weary, and exhausted, so unlike the radiant faces of Renoir's young women. There may be beauty in the ballerinas' poses and movement, but no joy in their execution. Rarely do we glimpse a smile.

By Edgar Degas - Metropolitan Museum of Art, online collection (The Met object ID 110000595),

Public Domain, Link

These young ballerinas were known as the "little rats" of the Paris Opera. Some were recruited as young as six. They worked hard for 10 to 12 hours a day, paid little with no compensating fame or respect, and then discarded when they got too old and were no longer needed, sometimes ending up as prostitutes.

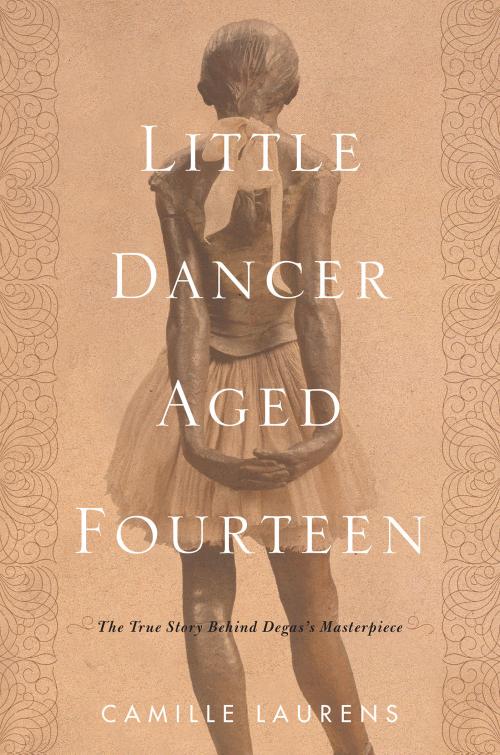

The most famous of these rats is Marie van Goethem, part of a family that emigrated from Belgium. She is the girl who posed for Degas for his sculpture "Little Dancer Aged Fourteen." Originally created in wax, about three feet tall, it was dressed up like a doll in tiny tutu, slippers, and wig. It was exhibited only once during Degas' lifetime, behind glass in 1881 to much contoversy. After Degas' death, multiple copies were cast in bronze.

This ballerina's face is not turned away or hidden, but instead sticks upward with a defiant, haughty expression. Her eyes are almost shut. This is not what we want. We want her to glow like a joyful and optimistic girl of fourteen. We want her eyes spread wide as she sees the world for the first time. But she refuses. She looks instead like a juvenile delinquent, and not the cute gamin kind.

In her book Little Dancer Aged Fourteen: The True Story Behind Degas's Masterpiece, French novelist Camille Laurens tries very hard to discover everything she possibly can about little Marie, and what Degas was trying to make the viewer see in his projection of her.

Certainly I felt very relieved learning that Degas never slept with his models. In fact, Degas seems to have been virtually celibate in his adult life. But how does Degas' notorious misogyny fit into this equation?

Did Degas deliberately misshape the Little Dancer's head to make her look simian? Or was that subconsciously done? Is that what he saw when he looked at Marie? Or was it a type of social commentary of the effects of poverty? Was Degas working like a naturlist writer like Victor Hugo or Zola exposing to us the ugliness in the world?

Why did Degas put Marie's age in the title of the sculpture? Was he protesting child labor and the economic situations that would put a 14-year-old girl through the life of the little rat? Was the sculpture an attack on the bourgeois audience who indirectly forced these girls into this life?

These are the types of questions raised by the book, which obviously does not provide definitive answers. The Little Dancer is a work of art, and it is often the very nature of art to ask questions rather than answering them. You want answers, you go to math or science.

This Sunday I'll have the opportunity to go to the Metropolitan Museum and pay the Little Dancer another visit, and I'll try asking her directly. I feel much better equipped having read Camille Laurens' book.