Reading “The Fatal Gift of Beauty”

September 3, 2011

Roscoe and New York, N.Y.

Sometimes it seems a miracle that people can communicate at all. Our face-to-face conversations comprise a medley of phrases, half-words, grunts, hums, hesitations, grimaces, and gestures. Only slivers of visual imagery and sound are perceived by the senses, and the brain strives in fill in the blanks. Everything is then interpreted in accordance with — and building upon — our unique inner lives. How easy it is to mishear a word, misread a smile or wink, and completely invalidate what we thought we heard or saw. It's a wonder that we don't daily collapse in complete surrender to confusion and embarrassment.

Even prose that's been carefully composed in fully-formed sentences and paragraphs is easy to misinterpret. Every writer knows the perils of using satire and irony: Articles in The Onion are routinely believed to be actual news items, and humorist Art Buchwald once estimated that about 25% of his readers believed his columns to be factual. But that's only the most obvious problem. Readers always bring along their own psychological baggage to the written word, and everything they read must fit into those bags.

Our evolutionary heritage has given us a powerful gift for interpreting the world known as pattern recognition, but this is a mixed blessing. Our skills at pattern recognition are so acute that we often see patterns where they do not actually exist. The human mind does not tolerate randomness. Give us a collection of random dots and lines, and we see pictures and faces. We perceive objects in the random formations of clouds just as our ancestors organized the random sprinklings of nighttime stars into the archetypal images of the constellations. Our widespread familiarity with optical illusions should be ample warning that we simply can't believe everything we see and hear, but it doesn't seem to help.

As a bonus, our over-active instinct for pattern recognition lets us formulate elaborate connections between unrelated people and events that come together in grand conspiracy theories. We constantly fabricate motivations in the over-determined universe where everything happens for a reason.

Deductive rational thought requires time and effort, and if we don't have that time, we can link pattern recognition with emotional responses into fast "blink" decisions. If we need to, we can later go back and shore up our first responses with more rational thought and justifications. This system usually works for us. As David Hume noted many years ago, "We speak not strictly and philosophically when we talk of the combat of passion and of reason. Reason is, and ought only to be the slave of the passions, and can never pretend to any other office than to serve and obey them."

But blink determinations can be particularly hazardous when they overpower judgments that should more properly be reflective and analytical, such as determining if someone is guilty of a crime. But we all want shortcuts. If we see in the newspaper or on the news that somebody's been accused of a crime, what is the first thing we want to do? We want to see the face of the accused. We want to evaluate this individual without waiting for actual evidence, because we know — or at least we think we know — when someone "looks guilty" or is "acting guilty." The instinctual judgment comes first; the actual evidence must be assembled later

In making such evaluations, we should all be haunted by the ghost of Richard Jewell. This is the man who was widely believed to be guilty of planting a bomb at the 1996 Summer Olympics in Atlanta. Richard Jewell not only looked guilty but he "fit the profile" to a T. Those of us unfortunate to have read a book or two about criminal profiling, and the pathologies of serial killers played right along. I can remember telling everyone who would listen to me about all the markers that clearly indicated Richard Jewell was guilty, guilty, guilty. (The real bomber was later determined to be domestic terrorist Eric Robert Rudolph in pursuit of an anti-abortion and anti-gay agenda.)

Now consider how the problems of determining guilt or innocence might be compounded with a clash of language and cultures, and you will perhaps begin to understand the events surrounding the murder of British student Meredith Kercher on the evening of November 1, 2007, in Perugia, Italy. A struggle had occurred, her body was bruised, a knife had been thrust into her neck, she asphyxiated on her own blood, she was half undressed, and her body was covered in a blanket.

Somebody killed Meredith Kercher, and three people are now serving prison sentences for that crime: Rudy Hermann Guede was convicted on October 28, 2008, and in a separate trial, Raffaele Sollecito and American student Amanda Knox were convicted on December 4, 2009.

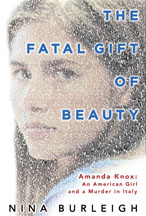

This murder and these convictions are the subject of journalist Nina Burleigh's fascinating book The Fatal Gift of Beauty: The Trials of Amanda Knox (Broadway Books, 2011). This is probably not a book I would have thought to read had I not known the author, but I learned a great deal from it. Burleigh plunges deeply into the culture of American and British students in Italy, their alcohol and pot-fueled parties, and even the petty but intense rivalries of college-age women who find themselves accidental roommates. On the prosecution side, she explores in particular the life and motivations of Giuliano Mignini, whose experiences with a previou case caused him to interpret evidence -- such as footprints of only one foot -- in very special ways involving Masonic conspiracies.

It is indicative of the instinctual and emotional nature of this case that so much of it centers on the face of the American defendant. It is the image of Amanda Knox that propelled this case to widespread attention, and she truly has one of the most enigmatic faces since the Mona Lisa. Some people look at her and see an innocent Madonna; to others what jumps out is a stone-cold psychopathic killer.

Compounding these first impressions is Amanda Knox's personality. She seems to be a very strange young lady, at times oddly devoid of emotion, and sometimes given to inappropriate comments or actions. Every time Amanda Knox does something weird in the pages of Burleigh's book, the reader cringes a bit, knowing that she's being watched very closely and anything inappropriate will further convince her prosectors and the public of her guilt.

Keep in mind also that these events took place during the "whore-ocracy" of Prime Minister Sylvio Berlusconi, which has had an effect of distorting images of women in the media, and creating resentments among professional women for those women who instead are publicly sexual. This is also a country where members of the press can be bullied by police and prosecutors:

-

Italy is a sunny place, but free speech is rather chilled. The nation was ranked seventy-ninth in press freedom in 2009. For years, major journalists who criticized Sylvio Berlusconi were routinely fired. Prosecutors had the right to throw journalists in jail on fairly flimsy grounds, and most Italian journalists assumed that their phones were tapped. Courageous, smart Italian journalists could be found on the front lines of stories about war and social issues, but those who did investigative work generally didn't take on the government. (p. 240-241)

The Italian justice system has undergone some reforms since the Roman days, but it still has flaws regarding the presentation of evidence that would not be tolerated in American courts. However, it is useless to describe these differences to anyone in Italy. Whatever flaws are identified, the Italians will correctly note that they don't have capital punishment like in America. Adding to justifiable anti-American attitudes is an incident almost unknown to American but still very vivid in the minds of Italians. This is what they call the Strage del Cermis ("Massacre of Cermis") where the wing of a low-flying U.S. military plane severed the cable of an aerial tramway, causing the deaths of 20 people. Tried in U.S. courts, the pilot and navigator were acquited of all manslaughter and homicide charges.

To me, the most fascinating part of The Fatal Gift of Beauty is Nina Burleigh's discussion how evidence builds on itself. Human beings struggle for coherency and consistency, so we tend to reinterpret evidence in the light of other evidence that we regard as more persuasive. In most criminal justice systems, a suspect's confession is considered the most persuasive piece of evidence, so it's not surprising how a confession can cause other evidence — even supposedly objective evidence like fingerprints and DNA — to be re-evaluated in light of a confession. Perceptions and memories magically morph with a simple change of perspective.

And it's not as if no one is cognizant of these problems. Indeed, the all-important confession is routinely obtained through the Reid technique, developed in the United States in the 1940s but now known to lead to false confessions. The Reid technique consists of psychological battering over an extended period of time, and in the case of Amanda Knox, it was followed by a contrasting comforting session in which she was coaxed to imagine what she might have experienced had she been present at the crime.

One revealing statistic that Burleigh presents: Of convicts originally convicted for rape or murder but freed by DNA evidence by the Innocence Project, about 25% had actually confessed to the crime they had not committed! Knox's "confession" is likely to be in this category, for it implicated her employer, Congolese immigrant Patrick Lumumba, who turned out to have a rock-solid alibi. His role in the murder was then replaced with another man of African birth, Rudy Hermann Guede.

By the time of the trial of Raffaele Sollecito and Amanda Knox, the prosecution had assembled a reasonably coherent narrative of the events that led to the murder of Meredith Kercher, but every detail of which was problematic. The prosecution was in too deep to back out. They were in the middle of a dollar auction: The more money and time and reputation that's been committed to a case, the less likely it will be stopped.

The Fatal Gift of Beauty is a revealing and well-researched book that clarifies a lot about a case that continues to intrigue. Let us hope the story is not yet over. Sometimes miscarriages of justice can work themselves out, but often it takes a very long time.

On the same day I finished The Fatal Gift of Beauty, the morning newspaper brought news of the release of the West Memphis Three — teenagers convicted in 1994 of the horrific Robin Hood Hills murders in West Memphis, Arkansas. As in the Meredith Kercher case, there was the same lack of physical evidence but the three accused teenagers compensated for many other incriminating characteristics. They were convicted for their strange appearances, their interest in goth culture and magic, their tastes in music, and even the number of black tee-shirts they owned. After this casting coup, the prosecution could easily formulate a plot involving Satanic ritual.

Like Amanda Knox, the West Memphis Three were convicted for who they were rather than what they did. Unfortunately, this case also shows how difficult it is to reverse such a conviction. Now in their 30s, the West Memphis Three were not exonerated, but instead persauded to plead "no contest" dishonestly in order to get out of prison.

We know that the wheels of justice turn slowly, but civilized societies must find better ways to shift them into reverse.