It’s not clear if Beethoven and the Archduke Rudolph (Day 193) were true friends, but they definitely had a mutually beneficial relationship: Rudolph was Beethoven’s most steadfast patron, and he maintained an extensive music library that Beethoven used. In return, Beethoven dedicated many compositions to Rudolph, and beginning in the winter of 1803–04, Rudolph was Beethoven’s only student of composition, an arrangement that lasted well over a decade.

It is likely that Beethoven sometimes viewed his teaching commitment to Rudolph as an unwelcome burden. Many letters exist from Beethoven to Rudolph why he can’t make their appointment on a particular day, with excuses mostly related to poor health.

The most extensive source of information about Archduke Rudolph’s life and music is this book by pianist and musicologist Susan Kagan (susankagan.com): pendragonpress.com/book.php?id=444

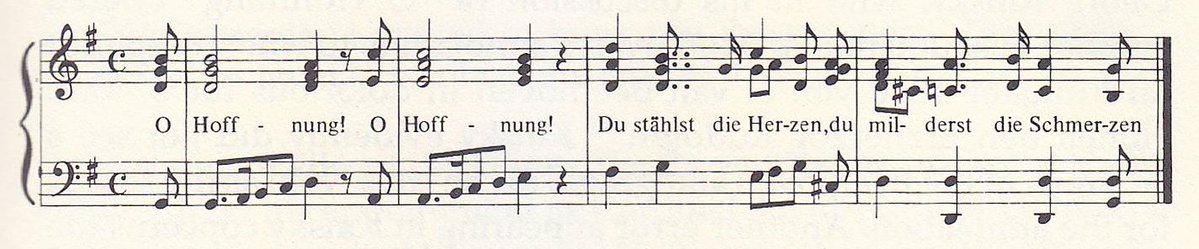

In the spring of 1818, Beethoven gave the Archduke Rudolph a composition assignment: To write variations on a tune that Beethoven supplied, with the text: “O Hope! O Hope! You steel the heart, you soften the pain.” These four measures are catalogued as WoO 200.

It is sometimes said that the text of “O Hoffnung” derives from Christoph August Tiedge’s Urania and the poem “An die Hoffnung,” which Beethoven had set earlier (Day 185) and more recently (Day 283). But that is not so. It is likely Beethoven himself wrote the text.

#Beethoven250 Day 308

“O Hoffnung” theme for Archduke Rudolph (WoO 200), 1818

Just four measures long, this piano theme was the basis for a set of variations by Archduke Rudolph.

Although several other composers were to write variations on themes by Beethoven (most notably Robert Schumann and Camille Saint-Saëns), “O Hoffnung” is Beethoven’s only composition specifically intended for someone else’s variations.

Archduke Rudolph wrote a set of 40 variations on Beethoven’s four-measure tune. While Rudolph’s composition was in progress over the next year or so, Beethoven made corrections and suggestions, and nixed some variations entirely.

The Archduke Rudolph’s variations were published by Steiner in December 1819 as part of the Keyboard Museum series. Here are the original title pages and first page of the score: beethoven.de/en/media/view/…

The complete score of the Archduke Rudolph’s variations is available online courtesy of the Duchess Anna Amalia Library in Weimar, Germany:

haab-digital.klassik-stiftung.de/viewer/resolve…

The title page reads (in English translation) “Exercise composed by Ludwig van Beethoven, forty times varied and dedicated to its author by his pupil, R.E.H,” the initials standing for “Rudolph ErzHerzog,” the German world for “archduke.” Considering the Archduke Rudolph’s relationship to the royal family, and his recent elevation to the position of Cardinal within the Catholic Church, it would have been inappropriate for his name to appear as composer, but everyone knew who it was.

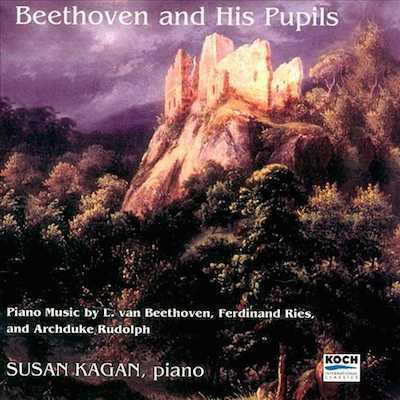

Archduke Rudolph’s “Forty Variations on a Theme by Beethoven” is not available on YouTube or Spotify. The only recording seems to be this one by pianist Susan Kagan, the author of the book on Rudolph: arkivmusic.com/classical/albu…

About 30 minutes long, Archduke Rudolph’s composition begin with a fantasia introduction prior to the theme. The first 35 variations all follow the 4-bar structure of the theme but with different tempi. Variation 36 breaks the pattern, and the long finale includes a double fugue.