On the 15 November 1815, Beethoven’s brother, sometime business manager, and sometime composer Kaspar died of tuberculosis, leaving behind his wife Joanna, and a nine-year-old son Karl. To his old friend Ferdinand Ries, Beethoven wrote a week later “My poor unfortunate brother has just died. He had a bad wife.… During his last years the poor fellow had changed greatly; and I may say that I mourn his loss with all my heart …” (Beethoven Letters No. 572)

As a result of Beethoven’s bitter feelings towards Joanna (who he would later call the Queen of the Night), and his own fatherly instincts, a nasty custody battle of young Karl ensued. For details, see Ch. 18 of the late Maynard Solomon’s biography “Beethoven.”

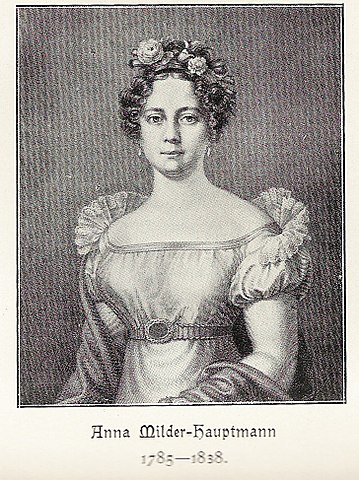

On 6 January 1816, Beethoven wrote to Anna Milder-Hauptmann. As the 19-year-old Anna Milder, she had sung the title role in the first performances of Leonore in 1805. Ten years later, married and more accomplished, she sang Fidelio in Vienna and Berlin to great acclaim.

In his letter, Beethoven congratulates Frau Milder-Hauptmann for her Berlin performances and writes:

“That composer can count himself fortunate whose fate it is to serve your Muses, your genius, your splendid qualities and excellent talents — and that I certainly do — Whatever may befall, anyone near you can only call himself a man in line. I alone am rightly entitled to the respectful name of Captain …” (Beethoven Letters, No. 596)

In German, “man in line” is Nebenmann and “Captain” is Hauptmann, her married name.

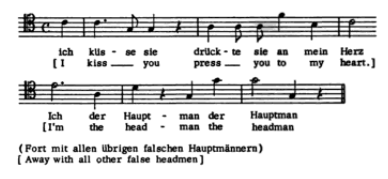

In a postscript, Beethoven writes “My poor unfortunate brother has died — that is the reason for my long delay in writing.” He suggests that he might write another opera for the soprano to be staged in Berlin, and then includes six measures of music, catalogued as WoO 169.

Here’s how the WoO 169 music is reproduced in Thayer / Forbes (p. 633) with translation. The first full measure is the beginning of the Fidelio Overture (Day 267). It’s not clear if Beethoven intended this music to stand by itself, or to be arranged into a canon.

#Beethoven250 Day 291

Canon “Ich küsse sie” (WoO 169), 1816

The music as originally written, and then arranged contrapuntally.

On 24 January 1816, Beethoven wrote two canons in the album of English pianist Charles Neate, who had come to Vienna in hopes of becoming Beethoven’s composition student. (He did not.) The two canons were eventually catalogued as WoO 168.

The texts of the two WoO 168 canons come from Johann Gottfried Herder’s “Scattered Leaves,” a collection of loosely translated Persian poetry from which Beethoven had obtained texts for his songs “Der Gesang der Nachtigall” (Day 261) and “Die laute Klage” (Day 279).

The two WoO 168 canons are:

“Das Schweigen” (Silence): “Learn to keep silent, friend, Speech is like silver, but silence at the right moment is pure gold,” and

“Das Reden” (Speech): “Speak, when it’s for the good of a friend. Speak, to say something nice of a fair one.”

When writing the two WoO 168 canons in Charles Neate’s album, Beethoven alluded to their subjects in his inscription, “My dear English compatriot, while you are silent and speaking [Schweigen und Reden], remember your sincere friend Ludwig van Beethoven.”

#Beethoven250 Day 291

Canon “Das Schweigen” and “Das Reden” (WoO 168), 1816

A studio recording of both canons with animated score.

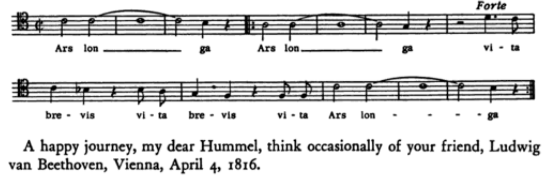

Beethoven eventually wrote three canons on the famous Latin aphorism “Ars longa, vita brevis” (Art endures; life is short). The first one is WoO 170, which Beethoven wrote in the autograph album of Johann Nepomuk Hummel. Here’s how it’s reproduced in Thayer / Forbes (p. 641):

#Beethoven250 Day 291

Canon “Ars longa, vita brevis” (WoO 170), 1816

A studio recording of the music arranged in the form of a canon.