As the French army approached Vienna, the royalty and aristocrats of Vienna began exiting the city. On 4 May 1809, the Empress departed, accompanied by Beethoven’s friend and patron the Archduke Rudolph.

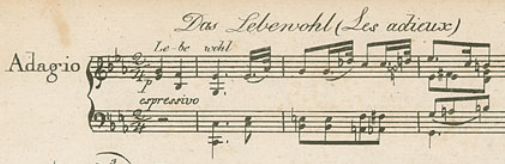

Prior to Archduke Rudolph’s departure from Vienna, Beethoven composed a piano piece for him entitled “Das Lebewohl” (“The Farewell”) with the inscription “The Farewell, Vienna, May 4, 1809, on the departure of his Imperial Highness the revered Archduke Rudolph.”

The piano piece “Das Lebewohl” that Beethoven presented to Archduke Rudolph would eventually become the first movement of Beethoven’s Piano Sonata No. 26, but Beethoven would not complete that work until later in the year on the Archduke’s return to Vienna.

“Das Lebewohl” begins with a horn call consisting of three slow descending intervals above which Beethoven wrote in the score “Le-be-wohl.” (The title “Les Adieux” was later added by the publisher against Beethoven’s wishes.)

#Beethoven250 Day 216

Das Lebewohl for Piano (Opus 81a, mm 1), 1809

The “Das Lebewohl” movement alone is how Beethoven first wrote it. (Don’t listen to the other two movements until Beethoven composes them later this month!)

“Das Lebewohl” has a slow forlorn introduction, but even when it speeds up, the work maintains a bittersweet tone. Theodor Adorno notes that “the clatter of horses’ hooves moving away into the distance carries a greater guarantee of hope than the four Gospels.”

The French army reached the outskirts of Vienna on 11 May 1809 and began firing howitzers on the city. “Rich and poor, high and low, young and old at once found themselves crowded indiscriminately in cellars and fireproof vaults.” (Thayer / Forbes, p. 465)

During the bombardment of Vienna, Beethoven “spent the greater part of the time in a cellar in the house of his brother Caspar, where he covered his head with pillows so as not to hear the cannons.” (according to Ferdinand Ries, Thayer / Forbes, 465)

In covering his head with pillows during the bombardment of Vienna, Beethoven could have been protecting his ears from further damage, but another explanation is plausible: As his hearing deteriorated, Beethoven also paradoxically became more sensitive to loud noises.

Another famous composer was also suffering under the attack of Vienna:

“On May 12 the great bombardment of the city started, and a cannon fell with a tremendous noise quite near Haydn’s house. The house shook as in an earthquake and the members of Haydn’s entourage were scared out of their wits. Not so the old invalid, who exclaimed above the uproar: ‘Children, don’t be frightened; where Haydn is, nothing can happen to you.’ … For twenty-four hours the bombardment went on, shattering the poor man’s nervous system. When Vienna capitulated and quiet was restored, the invalid, at whose doorstep Napoleon had placed a guard of honor, was unable to recover. He suffered no pain, but his strength was ebbing. On May 26 kind fate allowed him one great joy. A French officer of hussars, by the name of Clément Sulemy, called and after conversing with the master about The Creation, sang to him the aria “In native worth.” … Haydn could not restrain his tears of joy and assured the singer as well as the people in the house that he had never before heard the aria sung in so masterly a manner.” (Karl Geiringer, “Haydn,” p. 189)

Joseph Haydn died 5 days later at the age of 77.