Beethoven’s Opus 35 is often called the “Eroica” Variations, but that’s anachronistic because the Eroica Symphony hadn’t been composed yet. They’re really the “Prometheus” Variations because the theme originated in “The Creatures of Prometheus” ballet (Day 136).

When Beethoven wrote to his publisher that his new variations “are worked out in quite a new manner,” he wasn’t exaggerating about Opus 35. It begins with a section labeled “Introduction with the Bass of the Theme,” which is the bare bass played with octaves.

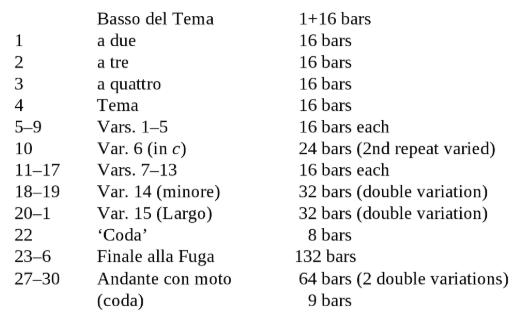

This is followed by sections labeled A Due, A Tre, A Quattro, in which that bass theme is progressively harmonized with additional voices. Finally we hear the full Theme — the tune already familiar to the Viennese audience from “The Creatures of Prometheus.”

“Thus,” writes Barry Cooper, “the stiff, unharmonized bass line seems gradually brought to life during four variations — an echo of the Prometheus ballet in which the statues were brought to life.” (“Beethoven,” p. 128)

This buildup from bass to harmony also resembles Baroque forms such as the passacaglia and chaconne. It might symbolize the historical progress of music, or the composer’s own process of building up a work from individual components.

After the theme is stated, the numbered variations begin from 1 to 15, followed by a Coda and then a Finale Fugue, which isn’t really the finale because it’s followed by a section marked Andante con moto that consists of additional variations that constitute the real coda.

#Beethoven250 Day 161

Variations and Fugue on a Theme from “Prometheus” (Opus 35), 1802

Korean pianist HaeSun Paik in a spectacular performance.

Beethoven had originally told his publisher that Opus 35 would consist of 30 variations, but the score contained only 15 variations labeled with numbers. In a letter to his publisher on 8 April 1803, Beethoven explained the discrepancy:

“As to the variations, about which you think that there are not as many as I state, you are certainly mistaken; my difficulty was that they could not be indicated in the same way; for instance, in the grand ones where the variations are merged in the Adagio, and the Fugue, of course, cannot be described as a variation; and similarly the introduction to these grand variations which, as you yourself have already seen, begins with the bass of the theme and eventually develops into two, three and four parts; and not till then does the theme appear, which again cannot be called a variation, and so forth. But if you cannot make head or tail of this, send me a proof, as soon as a copy has been printed, together with the manuscript, so that I myself may not be confused.”

Although it doesn’t seem that Beethoven was ever called upon to number the variations as he described, fortunately Barry Cooper has done us the service in a table on page 72 of his book “Beethoven.”

Beginning with “Var. 14” in Cooper’s chart, Opus 35 is entirely through-composed with no repeat marks. What would normally be a repeat within Variations 14 and 15 becomes a variation within the variation, hence the term “double variation.”

#Beethoven250 Day 161

Variations and Fugue on a Theme from “Prometheus” (Opus 35), 1802

The great French pianist Pierre-Laurent Aimard, performing on a stage that’s obviously been used for other purposes.

Will Beethoven ever compose another set of piano variations as intricate and as exhilarating as Opus 35?

Stay tuned!